Water Scarcity: Turning a regional challenge into a global opportunity

For much of 2016, the GCC has been pre-occupied by the economic impact of a liquid that comes out of the ground. Oil has long been the bedrock of regional economies. The revenues generated have built impressive cities, driven investment and modernization, and supported development across the region. However, if the GCC is to continue to grow and progress, there is another liquid to worry about – one far more important to the future of the region: water.

Matching Demand and Distribution

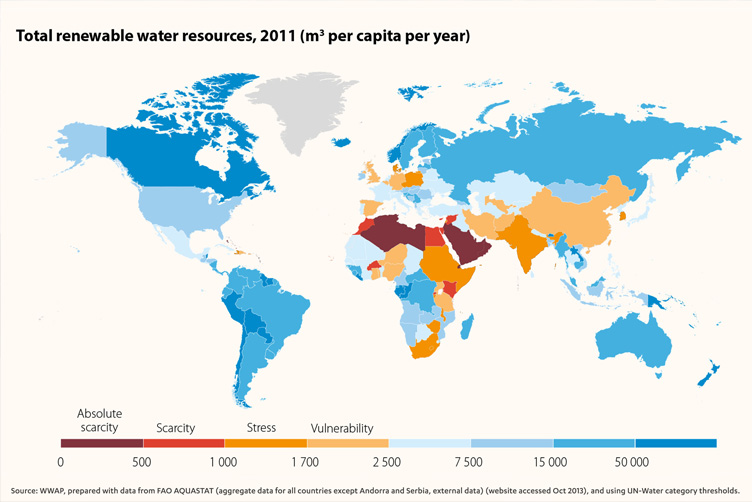

Water is fundamental to life, but ensuring a stable, sustainable supply remains a considerable challenge. Despite there being enough freshwater on Earth to support seven billion people an increasing number of regions are chronically short of water, due largely to its uneven distribution. The problem is exacerbated by hugely inefficient consumption patterns, with vast volumes of water wasted, polluted or unsustainably managed. Indeed, over the last century water use has been growing at more than twice the rate of population increase.]

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) – the world’s driest region – the problems are even more acute. More than half of the region’s population live under conditions of ‘water stress’, where demand outstrips supply. Although this is perhaps not surprising in an area containing 12 of the world’s most water-scarce countries, the scale of the difference between supply and demand is alarming.

According to World Bank data, the MENA region contains 6 percent of the global population, but less than 2 percent of the world’s renewable water supply. It is not uncommon for the region’s countries to generate renewable water per capita of less than 1,000 m3 per year.

Research published by NASA and the University of California Irvine in 2013, revealed how the Middle East dramatically depleted its freshwater reserves between 2003 and 2009. During this seven-year period, the volume of the region’s freshwater reserves decreased by 143.6 cubic kilometers – among the largest liquid freshwater losses on the planet during this period and equivalent to almost the entire volume of the Dead Sea. In the UAE alone, the water table has dropped by around 1 metre per year over the last 30 years, and the country is projected to run out of natural freshwater resources in about 50 years.

Consumption out of Control

These rapidly declining water reserves would be a serious challenge even if demand was contained. However, if we consider consumption the Middle East also has some of the world’s highest rates of water consumption. Bahrain, for example, uses 220 percent of its available renewable water reserves every year, but this figure rises to 2,465 percent of renewable reserves in Kuwait. In Saudi Arabia, the figure is 943 percent, with research from King Saud University estimating Saudi Arabia’s daily average per capita consumption at 265 liters.

Water consumption is most significant in the agricultural sector, which frequently accounts for 80 percent of annual demand in the region. There are other factors at play, too. The growth in industrial use of water is tightening the squeeze, while urbanization and improving lifestyles continue to drive high water consumption among citizens going about their normal activities. Everyday tasks such as gardening and car washing are using considerable water resources.

The overall prognosis is not good, and it is getting worse. With the pressure on water supply set to increase yet further as population growth and the effects of global climate change take their toll, water availability per capita in the MENA region is expected to halve by 2050.

Commercial Impact of Water Scarcity

Water scarcity does not only have a societal impact, it also has a considerable commercial impact. It is one which is likely to increase and intensify if action is not taken.

According to the World Bank, water scarcity could cost some regions up to 6 percent of their GDP over the next 30 years. It is also set to be a major driving force behind migration, increased food prices, and possible conflict.

The United Nations echoes these concerns. In its World Water Development Report 2016, it highlights its belief that reduced water availability will “affect regional water, energy and food security, and potentially geopolitical security”. It also cites threats to economic activity and the job market, as well as highlighting that “the right to safe drinking water and sanitation is an internationally recognized human right… integral to the realization of other human rights”.

A Huge Challenge – An Even Greater Opportunity

Producing enough water to support the Middle East’s growing population needs huge investment in water production facilities and infrastructure, as well as the energy these processes demand.

For more than 50 years, many regional markets have relied on desalination. Around 70 percent of the world’s current desalination capacity is in the Middle East, and it is growing. Saudi Arabia, for example, has earmarked US$ 24.3 billion of investment by 2020 to expand its desalination capacity.

However, the current desalination approach to water generation is simply not sustainable. It is energy intensive, relies on abundant oil, and comes at enormous environmental cost. Desalination plants worldwide emit an estimated 76 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. This is the equivalent of a country the size of Romania and, without substantial changes, it is expected to treble by 2040.

Finding a more sustainable approach to clean water production is therefore essential. This is not only a considerable challenge – but also a huge opportunity. Research from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) suggests that only 1 percent of the world’s desalinated water is currently based on energy from renewable sources – an indication of the massive commercial potential for the GCC to become a world leader in this innovative technology.

Renewable Water: An Affordable Reality?

According to the International Desalination Association, the demand for desalinated water is growing by 8 percent each year. The cost of ‘traditional’ desalination is already affordable for middle-income regions and countries. The ongoing use of fossil fuels to provide the energy necessary to power traditional desalination plants, however, is simply replacing one environmental problem with another.

Instead, the focus must be on desalination powered by renewable energy. Some forward-looking global markets are already taking action in this regard. In Western Australia, for example, the state government requires all new desalination plants to use renewable energy – with the result that the Perth Seawater Desalination Plant (SWRO) is powered by electricity generated by a wind farm north of Perth.

As the costs associated with renewable technologies continue to decrease, further advances in the technologies used both for generating renewable energy and the process of desalination will combine to make renewable desalination much more accessible.

New technologies – including pre-treatment processes, nano-technology filtering processes, and electrochemical desalination – are also making desalination more efficient. They are still at the early stages of development, however. We must push forward both their progress and the advancement of renewable technologies suited to desalination, such as solar thermal, solar photovoltaics (PV), wind, and geothermal energy. When those advances are harnessed together, we can make a real impact on the availability of renewable water not only in the Middle East, but across the globe.

The UAE has already recognized the potential of these commercial opportunities. Last year, during Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week, an agency of the Abu Dhabi government was instrumental in launching an initiative to explore ways to reduce the carbon footprint of desalination. It was also a key player in the launch of the Global Clean Water Desalination Alliance (GCWDA).

There are already reasons to be encouraged. In just five years, Abdul Latif Jameel Energy has become the largest GCC-based solar energy developer and one of the world’s leading solar energy solutions developers. It has invested and grown to develop a global and diversified renewable energy offering, with a presence in more than 15 countries.

This success story, and others like it, can help transform the water industry, too, a sector where Abdul Latif Jameel Energy is actively expanding its capabilities in the drive to create more sustainable water production that meets the population’s needs.

A Combined Approach

While desalination based on renewable energy is a clear route forward, this transformation cannot be done in isolation. There remains a need to continuously develop new and innovative approaches to confront the world’s water challenge, with governments, industry, science and society all playing their part.

Efficiency must be one pillar in this strategy. Heavily-subsidized water rates across the GCC have created a culture where water is recklessly wasted. Increases in water tariffs are being advocated in Abu Dhabi, while the Environmental Agency Abu Dhabi (EAD) has also installed flow restrictors in 55,000 households and 5,000 public buildings. A combination of practical and policy measures need to be fully considered in all countries facing ‘water stress’.

Scientific development is also key. Fostering partnerships between industry and academia, through initiatives such as the Abdul Latif Jameel World Water and Food Security (J-WAFS) Lab at MIT, is crucial to help translate pioneering research into practical solutions for communities around the world.

More than US$ 2 million was invested through J-WAFS Solutions in 2016 alone. Seed grant funding of US$ 1.3 million was awarded in May 2016, followed by five further grants of US$ 150,000 each in August 2016. There are currently 17 active J-WAFS projects addressing issues ranging from electro-chemical separation process for contaminated water, to using fungal yeasts to convert waste to food. Every cent of that money is helping to tackle the major problems facing mankind over the next 50 years.

Governments, too, must be active in confronting a shared and pressing problem. The Middle East is already making good progress in this area. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 national development strategy is explicit in recognizing the importance of water scarcity, committing the country to promoting “the optimal use of our water resources by reducing consumption and utilizing treated and renewable water”. It adds: “… the use of water in agriculture will be prioritized for those areas with natural and renewable water sources. We will also continue to collaborate with consumers, food manufacturers and distributors to reduce any resource wastage.”

At a regional level, the GCC is exploring the possibility of a cross-border water grid to enable water to be moved from areas of relative oversupply to those facing shortages. Sustainable ‘smart’ cities, at the heart of development strategies across the region, will also help communities understand and manage water consumption like never before.

Global Progress

Although there are encouraging signs across the GCC, water scarcity is a global issue and technological progress is being made around the world. It is up to GCC countries not only to keep the pace but to lead it.

Commercial opportunities are certainly available, as evidenced by Singapore’s successful development of NEWater – a high-grade reclaimed water process that now forms a key part of the country’s water sustainability strategy. Since 2000, treated used water has gone through a three-step process, built on advanced membrane technologies, that results in ultra-clean reclaimed water. It currently provides 30 percent of Singapore’s water needs, and is expected to serve 55 percent of the nation’s demand by 2060.

Similarly, in 2014 the Alto da Boa Vista drinking water plant in São Paulo, Brazil, installed and launched the first ultrafiltration drinking water system in South America. The system uses high-flow membranes from Koch Membrane Systems Inc. to double the treatment capacity of the plant and enable it to handle the high algae content of water drawn from the local reservoir and clarifiers during the dry season.

In Baja California Sur, Mexico, Sisyan LLC is investing in photovoltaic reverse osmosis plants that provide renewable desalination. And in Melbourne, Australia, a 600 m3/day sewer-mining scheme delivered by Arup provides recycled water to three sporting venues – “making use of water that would otherwise be flushed away”.

It’s Time to Act

The MENAT region cannot afford to be left behind by such initiatives to combat water scarcity. We have the skills and knowledge to be a global pioneer in this exciting field and benefit from the huge commercial opportunities it presents. Underlining our own commitment to becoming a global leader in the water solutions sector, Abdul Latif Jameel Energy announced the expansion of its capabilities with the establishment of Almar Water Solutions at the World Future Energy Summit 2017 held in Abu Dhabi in January. Almar Water Solutions, a provider of specialist expertise in water infrastructure development addressing the water security needs of our region’s and the world’s growing population through a sustainable program of desalination, water and waste water treatment and recycling and reuse initiatives. We are also exploring co-located development of renewable power generation and reverse osmosis desalination together to minimize the energy used in production and the carbon footprint of the desalination process. With an initial focus on water projects in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa, the team has proven experience in numerous international markets. Already, Almar Water Solutions is being considered for major infrastructure projects across the MENAT region, having recently pre-qualified for flagship opportunities, including those at King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) in Saudi Arabia and with the Federal Electricity and Water Authority (FEWA) in the United Arab Emirates.

Between 2007 and 2030, desalination capacity across the MENA region is predicted to expand from 21 million m3 per day to almost 110 million m3 per day. In turn, that will triple electricity demand for desalination to 122 TWh by 2030. So, the potential available to those who can lead the development of renewable desalination is clear.

However, it is imperative that further rapid progress is made. By meeting the water challenge head on, and encouraging investment, innovation and partnerships across society, the GCC can put itself at the forefront of a fast-growing, innovative industry that will become increasingly vital to global development in the coming years.

Added to press kit

Added to press kit