Stretching budgets . . . and lifespans

How to improve the effectiveness of healthcare spending

You can’t put a price on your health, so the saying goes. Except that somebody has to. Globally, healthcare spending is growing faster than most economies.[1] Is that because the more you spend, the better health outcomes you achieve? Unfortunately, not. Some countries seem to get better health outcomes for less money. High spenders take note; low spenders take heart.

In this article, we’ll explore the complex relationship between healthcare spending and health outcomes at the national level – and how countries can balance improving life expectancy with balancing the books.

Global healthcare spending is rising – rapidly

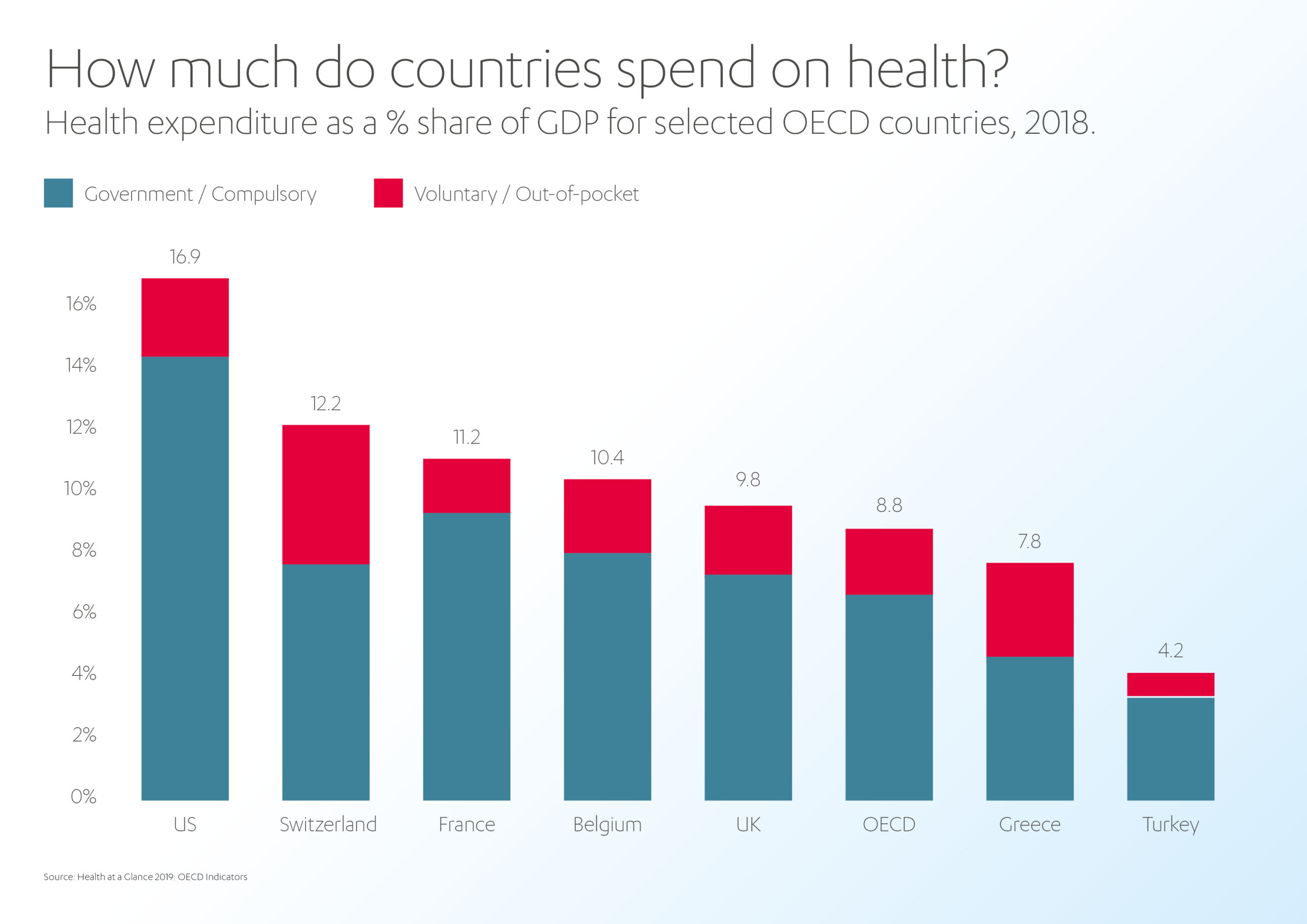

Over the past two decades, health spending has doubled in real terms, reaching US$ 8.5 trillion in 2019 and making up 9.8% of GDP, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). However, this spending is unevenly distributed, with high-income countries accounting for 80% of the expenditure and spending four times more on average per capita than low-income countries.[2]

Health spending comprises government expenditure, out-of-pocket payments by individuals, and contributions from individual and employer-provided health insurance and non-governmental organizations. Governments contribute about half of healthcare spending, while over 35% comes from out-of-pocket payments.[3]

Despite this increase in spending, at least half the world’s population still does not have access to essential health services, and 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty through out-of-pocket spending. In addition, over 930 million people (around 12% of the world’s population) spend at least 10% of their household budgets on healthcare.[4]

Meanwhile, the OECD forecasts that health expenditure will continue to outpace GDP growth in nearly every OECD country over the next 15 years. By 2030, health spending per capita is expected to reach 10.2% of GDP, up from 8.8% in 2018.[5]

Why is healthcare spending increasing?

Healthcare costs are on the rise due to a multitude of factors. With the world’s population expected to reach nine billion by 2037, there is a growing demand for healthcare services.[6] This is compounded by aging populations and the consequent rise of chronic, non-communicable diseases, which are often more expensive to treat.

Additionally, greater public health awareness and lifestyle changes have increased the demand for additional treatments, such as cancer screenings. More advanced treatments and technology also drive up the cost of healthcare.

Furthermore, anti-competitive trends in the healthcare industry, such as the consolidation of healthcare providers and insurers, can reduce competition and result in higher costs for consumers. Private investment and speculation can also contribute to the high cost of healthcare. The complexity of healthcare systems, funding, and administrative processes only add to the financial burden.

Does more healthcare spending equal better health outcomes?

The relationship between healthcare spending and health outcomes is complex. Numerous factors influence healthcare spending and health outcomes, making it difficult to establish a causal relationship.

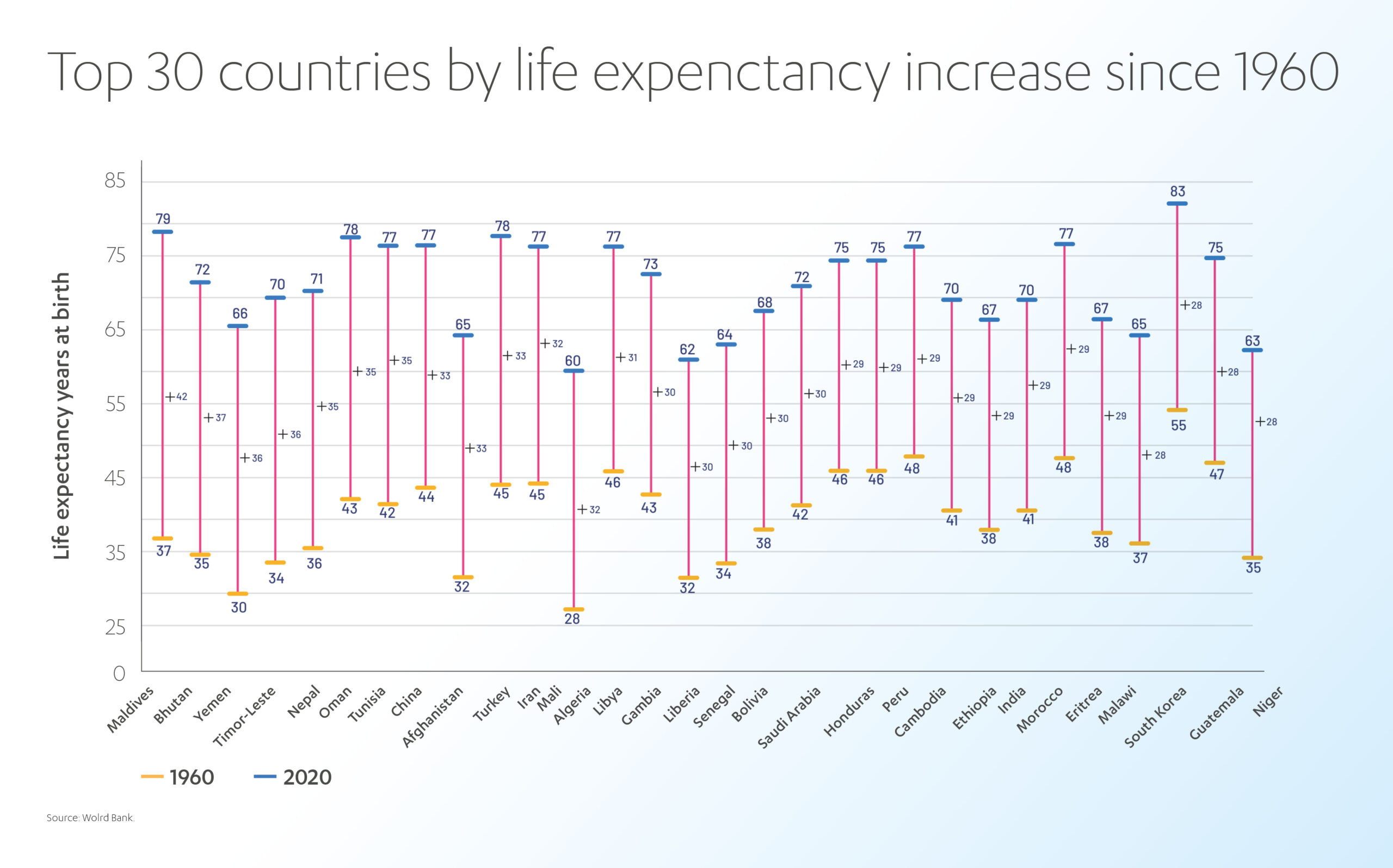

Income level is one such factor, as higher-income countries can afford to spend more on healthcare. However, high-income countries also have a range of other advantages that contribute to their population’s health. Over the past century, advances in various medical fields, such as sanitation, vaccines, and preventative healthcare, have significantly increased life expectancy globally. The effectiveness and efficiency of a given country’s healthcare system, its funding, and distribution, as well as the health of the population that uses it, all play a role in determining the relationship between healthcare spending and health outcomes.

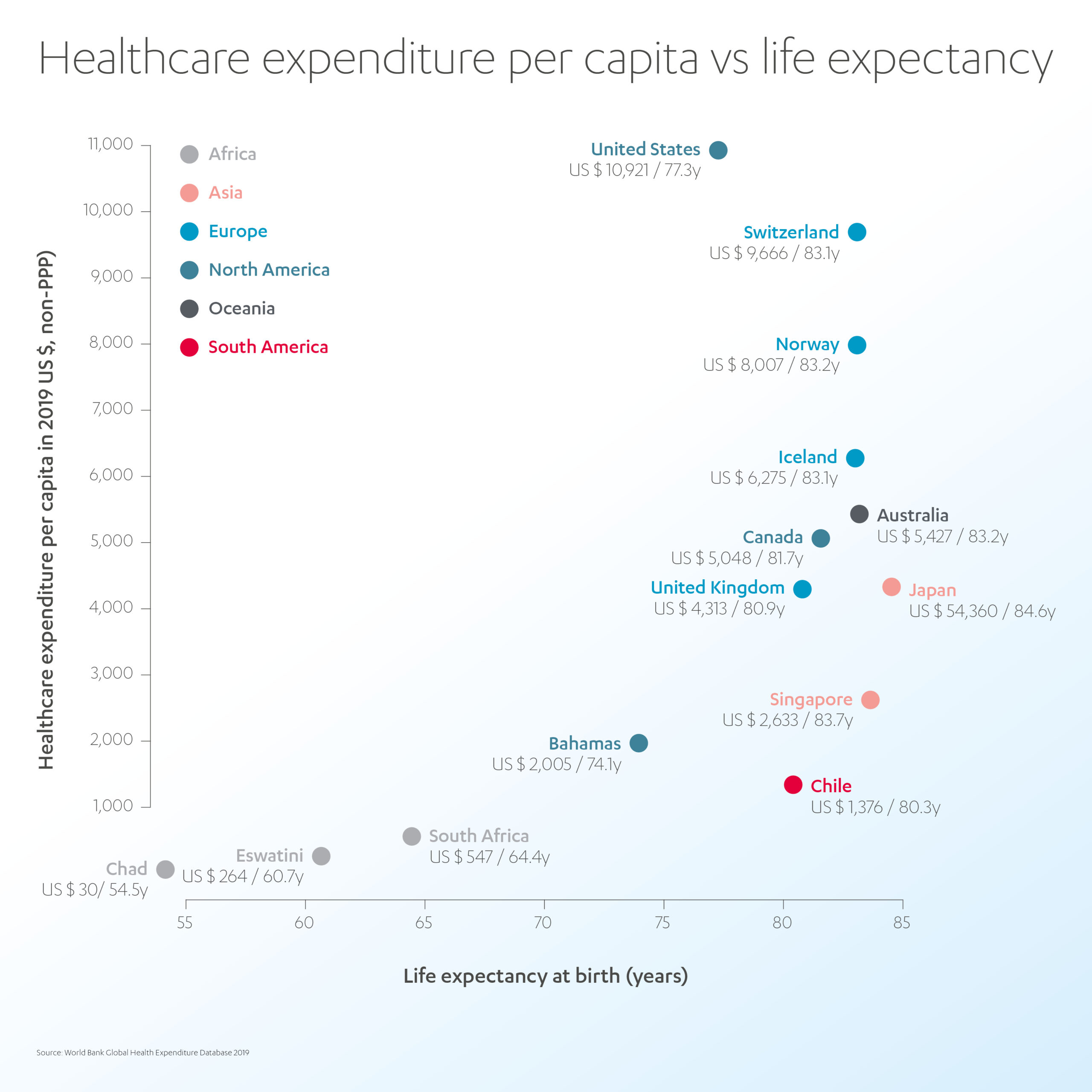

According to data from the World Bank, higher spending on healthcare typically leads to better health outcomes at a national level. The data from 178 countries shows that countries that spent more on healthcare had higher average life expectancies until reaching the 80-year mark.[7]

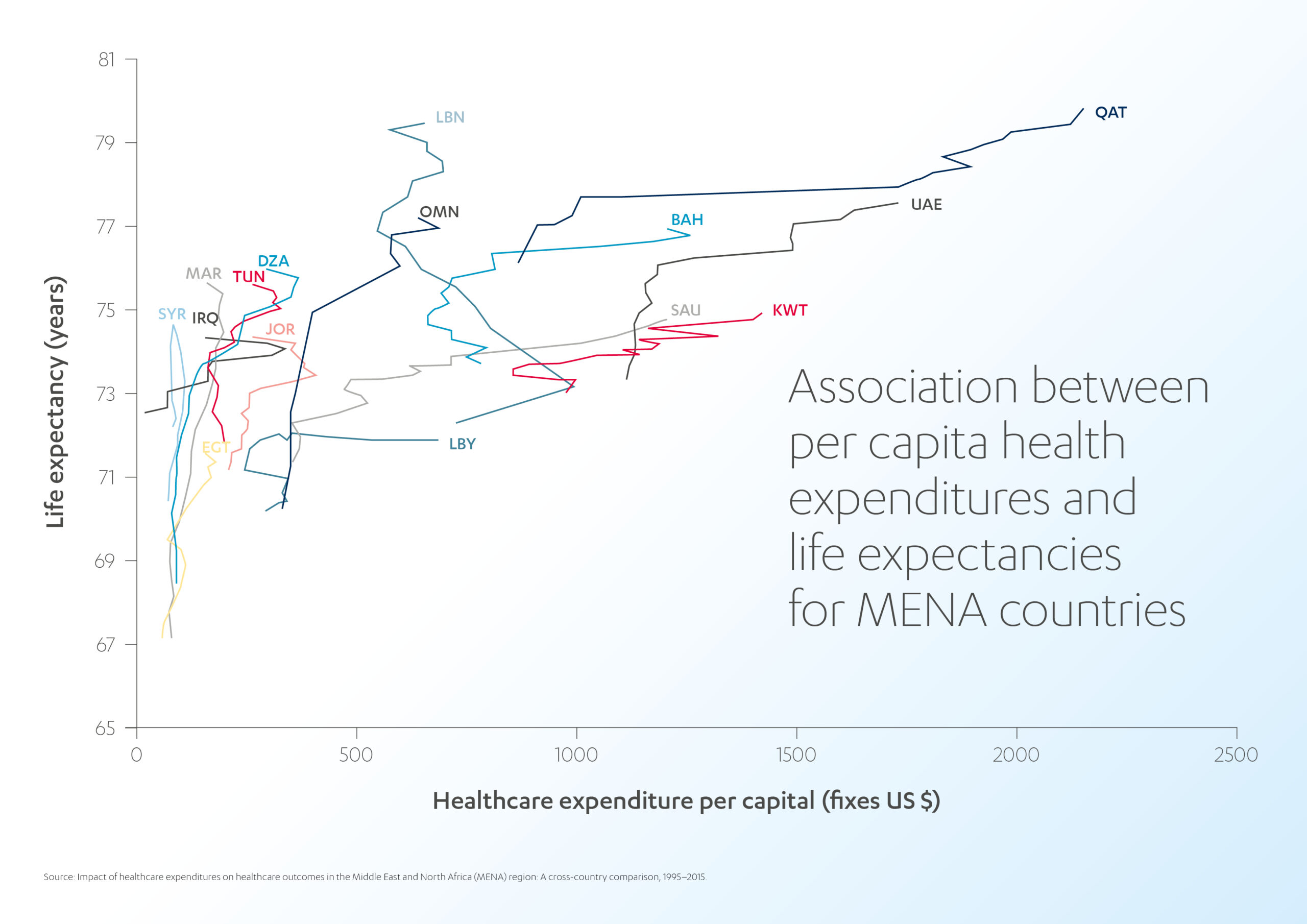

A similar trend was observed in the MENA region between 1995 and 2015, where increased healthcare expenditure was linked to a five-year increase in average life expectancy.[8] Lebanon stood out with the highest life expectancy at the lowest per capita expenses, as demonstrated by the almost vertical curve topping its contemporaries. The development pace of countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates was similar to that of developed countries like Japan and Germany.

However, the link between spending and outcomes is not clearcut, and there are notable exceptions.

Some countries spend more on healthcare per capita and have shorter life expectancies than those spending equivalent amounts. For example, Qatar and the UAE are outliers in the MENA region, as they spend more on healthcare but have a similar life expectancy to some countries that spend less.[9]

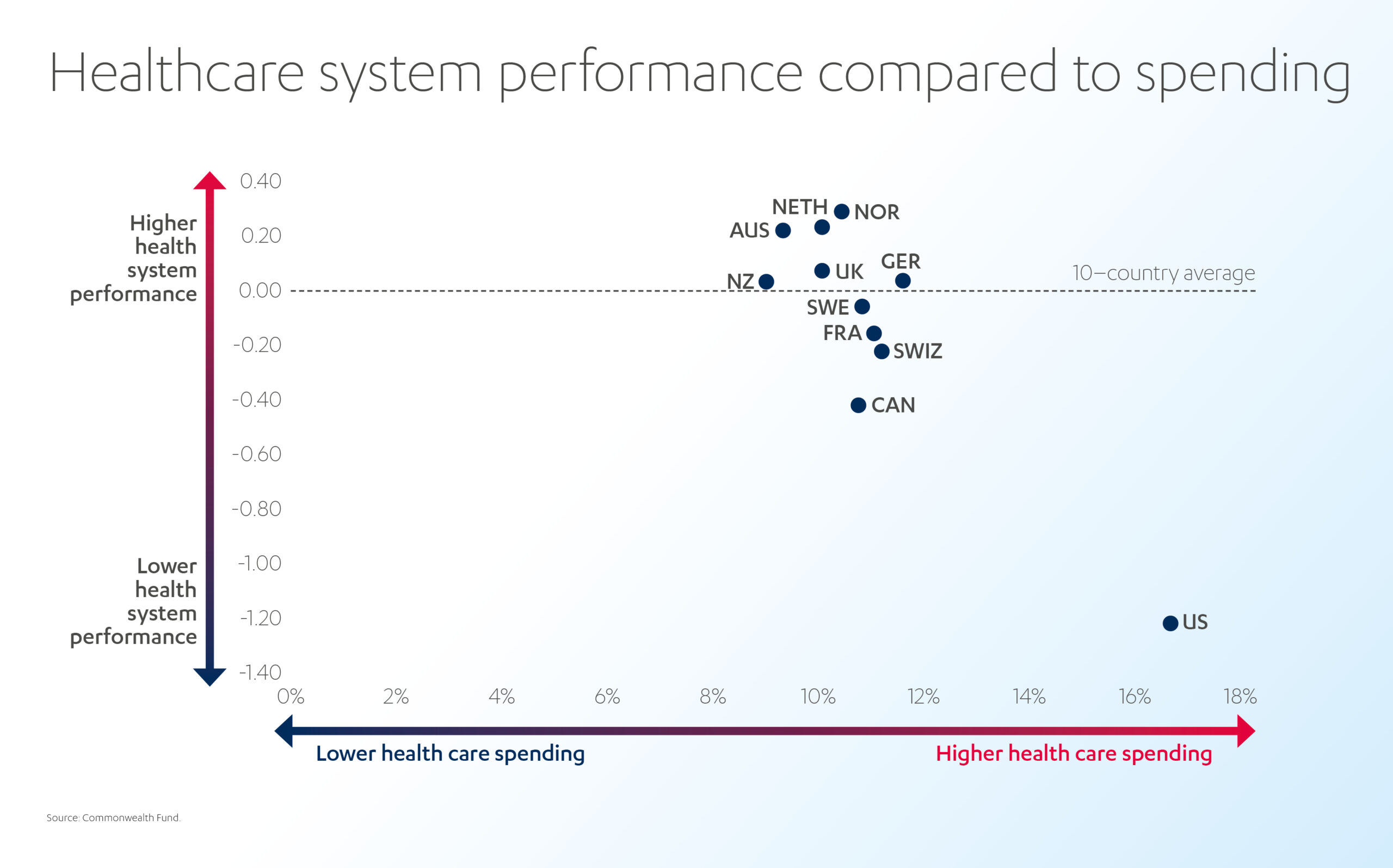

Globally, the United States spends the most on healthcare as a share of GDP but has a lower average life expectancy than many other countries that spend far less. This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors, such as inefficient healthcare systems, a population with a higher need for healthcare interventions, and lifestyle choices such as smoking and obesity.[10] On the other hand, Europe has shown mostly comparable results with varying levels of healthcare expenditure. The UK even reduced per capita costs while maintaining life expectancy.[11]

The best way to improve the effectiveness of healthcare spending is to make healthcare more affordable, accessible, effective, and efficient.

Removing cost barriers

Universal healthcare can reduce healthcare costs by lowering administrative expenses, promoting preventive care, and improving overall health outcomes. A study by the Commonwealth Fund found that countries with universal healthcare systems have lower per capita healthcare costs compared to the US, where 40 million citizens are without health insurance and must pay for treatment out of pocket.[12] Canada and the UK are examples of countries with successful universal healthcare systems that effectively control healthcare costs while providing comprehensive coverage to their citizens.

However, the World Health Organization (WHO) states there is no clear difference between health spending, priority, coverage, or life expectancy between systems funded through compulsory health insurance and those funded through government budgets.[13] An increase in health spending through either funding source can improve health outcomes, but spending alone is not enough to guarantee better health. The wide variation in life expectancy at different health spending per capita levels highlights this.

Widening access to care

Ensuring high-value health services are readily accessible to all communities and individuals, regardless of their socio-economic status, is not only a moral obligation but also makes economic sense. Primary care meets most of a person’s health needs throughout their lifetime, is more cost-effective than hospital care, and helps to reduce the likelihood of emergency interventions and hospitalizations.

Unfortunately, as discussed in a previous Abdul Latif Jameel Health article, about half the world’s population cannot access essential healthcare services.[14] Many countries in the Global South lack a well-developed health system and have limited access to healthcare services, particularly in rural areas. The lack of healthcare facilities, shortage of trained personnel, and poor infrastructure make it challenging for people to access essential health services, leading to longer wait times and higher healthcare costs.

For instance, sub-Saharan Africa has an average of 2.5 physicians per 10,000 people, compared to 33.5 in Europe. Maternal health facilities in low-income countries, especially Africa, are inadequate, contributing to the high maternal mortality rate.[15]

The issue is not confined to low and middle-income countries. Although developed countries in the Northern hemisphere have better access to healthcare services, disadvantaged communities still face barriers such as cost, lack of education, and even geographical constraints. For many people, healthcare is still a “postcode lottery.”

Like healthcare spending, access to care is a complex problem. But they are also closely linked. Ultimately, provided access to care is prioritized with appropriate business incentives and government coordination, anything that reduces healthcare costs should also improve access to care.

When China undertook a major reform to its healthcare system, strengthening the capacity of the primary healthcare system was its top priority. The government extended and removed barriers to care by investing in rural village clinics, town health centers, and urban community health stations and centers.[16]

In Sub-Saharan Africa, Philips has pioneered resilient, community-owned healthcare clinics offering integrated healthcare enabled by digital technologies and capacity-building services, like education and staff training. The Community Life Centers also include solar power units, clean water, LED lighting, and solutions for waste management, helping to drive economic and social development for the local population.[17]

Leveraging technology

Technology can play a significant role in improving the impact of healthcare spending by making the delivery of care more efficient, effective, and affordable. Some of the key ways technology can help to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of healthcare budgets include:

- Electronic Health Records (EHR): EHRs can help to improve the quality of care by providing a comprehensive view of a patient’s health history, reducing medical errors, and improving care coordination. The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) has implemented a comprehensive EHR system known as the NHS Spine, which has been credited with improving the quality of care and reducing medical errors.[18] In Kenya, the government has launched an initiative to create a centralized health information system, which will use EHRs to improve health outcomes and increase the efficiency of health services.[19]

- Telemedicine: Telemedicine allows patients to receive medical care remotely, which can help to reduce the cost of care, improve access to care, and reduce the burden on hospitals and clinics. Telemedicine has been rapidly adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and has proven valuable in providing remote care to patients worldwide.[20]

- Medical devices and diagnostic tools: Advancements in medical devices and diagnostic tools can help improve the accuracy and speed of diagnoses, reducing unnecessary testing and procedures and improving health outcomes. Abdul Latif Jameel Health and Butterfly Network are distributing Butterfly iQ+, a remote ultrasound device, throughout the Middle East, North Africa, Turkey and India to make medical imaging accessible to all—without the massive investment of traditional ultrasound scanners. Similarly, Abdul Latif Jameel Health’s partnership with San Francisco-based iSono Health is set to bring the world’s first AI-driven portable 3D breast ultrasound scanner to the Global South, potentially helping millions of women in the developing world access meaningful cancer treatment.

- Predictive analytics: Predictive analytics is being used to identify patients at risk for certain conditions, allowing for early intervention and improved health outcomes. In Europe, the EU-funded project “PREDICT” uses predictive analytics to improve care for patients with chronic conditions.[21]

- AI and machine learning: AI and machine learning are being used in countries to improve decision-making, automate tasks, develop new drugs, and provide real-time insights into patient health. In China, AI is used to enhance the accuracy of cancer diagnosis, reduce misdiagnoses, and improve health outcomes.[22]

Improving healthcare systems

Implement evidence-based best practices

Many treatments are low-value, unnecessary, duplicative, or even potentially harmful. In OECD countries, one in ten patients is harmed due to unnecessary treatments, and one in three babies is delivered by cesarean section, whereas medical indications suggest that C-section rates should be 15% at most.[23] Other examples of wasteful procedures include imaging for low back pain or headaches and cardiac imaging for low-risk patients.

Various methods can be employed to tackle this issue, such as information campaigns targeting patients and clinicians, implementing clinical guidelines, monitoring and reporting low-value care, evaluating the effectiveness of new medical technologies, and financial incentives. For instance, Queensland in Australia has taken the step to withhold payments to hospitals for certain events deemed as “never events.”[24] The Choosing Wisely campaign is a global initiative to reduce low-value care by promoting conversations between patients and healthcare providers about the necessity of specific treatments.[25]

Incentivize value-based care

Provider payment models can improve healthcare spending effectiveness by aligning incentives, creating competition, and promoting innovation. Examples include Pay-for-Performance (rewarding providers for quality and outcomes), Accountable Care Organizations (coordinating care for populations rather than billing for individual services), Public-Private Partnerships (leveraging private sector resources to increase the efficiency and impact of healthcare spending), and Value-Based Purchasing (reimbursing healthcare providers based on the value rather than volume of services).

Reduce hospitalization

Hospital inpatient care accounts for 28% of health spending in OECD countries, but research shows that up to 20% of hospital visits can be avoided.[26],[27] Effective primary care and information campaigns can reduce hospitalization and emergency care. For example, ambulance admissions could be reduced by between 8% and 18% in England, saving up to £238 million annually.[28] In the same country, telemedicine has been shown to reduce emergency admissions by 20% and attendance by 15% for patients with long-term conditions, including diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure.[29]

Improve hospital efficiency

Improving administration can lead to more outpatient surgeries, shorter hospital stays, and reduced medical mistakes or infections—saving time and money while improving patient outcomes. In Japan or Korea, patients often stay for as long as 15 days or more, while those in Denmark, Turkey, and Mexico stay for fewer than five days.[30] Time is of the essence, and not just for money. In OECD countries, hospitals spend over 10% of their budgets on correcting preventable medical mistakes or infections people catch during their stay.[31]

Reducing waste

Simplify insurance coverage, billing, and payment

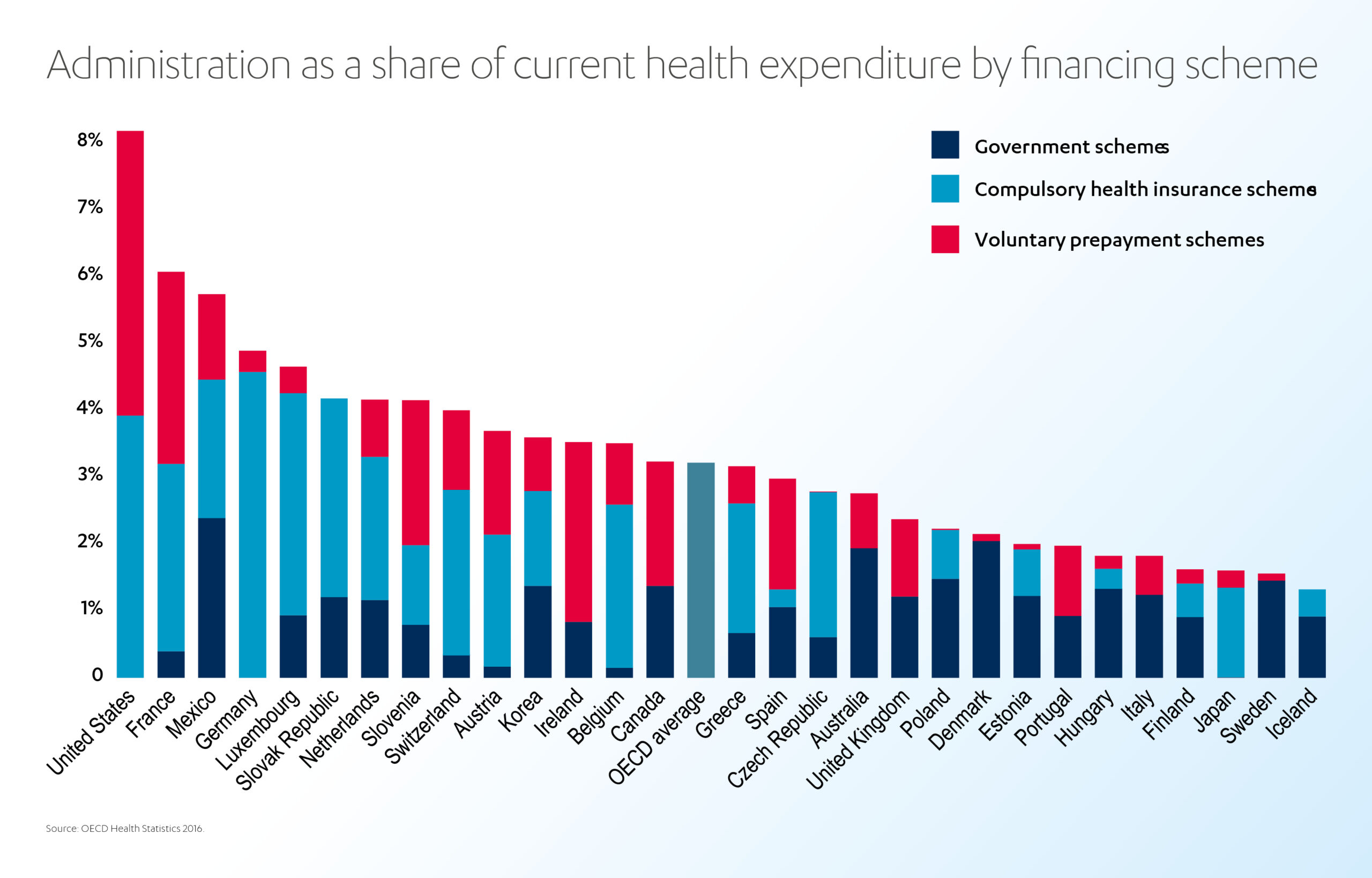

Administration accounts for around 3% of health spending but “varies in a ratio of one to seven across OECD countries, with no obvious correlation with health system performance.”[32] Systems with a single payer, such as social health insurance or government-funded, tend to have lower administrative costs than those with multiple payers and a free choice of insurers. Meanwhile, private insurance often has much higher administrative costs than public schemes.

Simplifying insurance coverage, billing, and payment through regulation, standardization, and legislation can help reduce costs and improve treatment access. For instance, Norway uses a standardized copayment system for physician fees, determined on a regional basis for all public sector physicians within a specific area and specialty.[33] The Commonwealth Fund affirms that collective negotiation and standardized payment for services at a national or regional level can simplify transactions, reduce errors, and free up resources for improved care.[34]

Reduce wasteful spending on pharmaceuticals

Pharmaceuticals are often overpriced, over-prescribed, poorly managed (or even discarded). As we explore in a previous article, the misuse of antimicrobials is a hazardous form of wasteful care—and one of the top 10 global public health threats, according to the WHO.[35] Almost 50% of antibiotic treatments globally are initiated with the wrong drug and without a proper diagnosis.[36] In OECD countries, pharmaceuticals comprise 20% of healthcare spending but don’t always add value for patients.[37]

Wasteful pharmaceutical spending can be reduced through various strategies, such as rapid diagnostic testing, incentives for doctors to prescribe generic drugs, and patient education. In some countries, such as France, Hungary, and Japan, pay-for-performance schemes have been introduced to incentivize doctors to prescribe generic drugs.[38] Greece even requires public hospitals to reach a 50% share of generic drug prescriptions.[39]

Allowing patients to discuss their medication-related concerns before starting a new treatment can also help to reduce waste (telemedicine is ideal for this). Improving procurement systems and negotiating drug prices can also help reduce waste. In Norway, for example, a drug procurement cooperation that includes all public hospitals has successfully negotiated a 30.4% average discount on purchased hospital medicines.[40]

Tackle fraud, abuse, and corruption

Corruption swallows 7% of healthcare spending, costing the world an estimated US$ 500 billion yearly.[41] High levels of corruption correlate with negative health outcomes, such as high infant and child mortality rates, decreased life expectancy, low immunization rates, and increased antibiotic resistance.[42] Corruption can take various forms, including theft and misappropriation of resources, absenteeism, informal payments, and counterfeit medical supplies. It often disproportionately affects more vulnerable patients, particularly those in poor health or with lower socio-economic status.[43] Effective anti-corruption measures include increasing accountability and enforcement, promoting transparency, and implementing preventative measures.

The US has made progress in fighting healthcare corruption through the efforts of an anti-corruption task force. The task force’s improved analytical capacity led to the recovery of US$ 1-3 billion in Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse over 10 years.[44] The success of anti-corruption efforts in low and middle-income countries has been varied. In India, an anti-corruption agency in Karnataka uncovered widespread corruption, but weak political support hindered their ability to secure convictions.[45] While in Uganda, anti-corruption efforts led to a marked decrease in bribery among healthcare workers, but this was accompanied by a devastating strike due to a lack of efforts to raise salaries and improve working conditions.[46]

Reducing demand for healthcare

One way to reduce healthcare spending is to help people avoid becoming sick in the first place.

As we explored earlier, improving access to primary care reduces the likelihood of more expensive emergency procedures and hospitalizations later on. Investing in infrastructure and social services, including housing, sanitation, transport, welfare, worker benefits, child-care support, and education improves overall health. Education is especially important, as it can raise awareness about healthy diets and lifestyles, including contraception and sexual health, thereby reducing the likelihood of developing serious and expensive health conditions. In countries where sexual health is stigmatized, promoting education and confidence in healthcare is crucial, particularly for women.

A healthy outlook?

Healthcare spending can go much further. Which is fortunate, because healthcare budgets can’t. Demographics and economics may vary, but all nations have significant opportunities to improve healthcare outcomes by leveraging best practice, incentives, regulation, and technology – while investing in public health, infrastructure, and social services. Over 8 billion people (and counting) depend on it.

[1] https://apps.who.int/nha/database

[2] https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041219

[3] https://www.who.int/news/item/20-02-2019-countries-are-spending-more-on-health-but-people-are-still-paying-too-much-out-of-their-own-pockets

[4] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

[5] https://www.oecd.org/health/health-spending-set-to-outpace-gdp-growth-to-2030.htm

[6] https://www.un.org/en/dayof8billion#:~:text=On%2015%20November%202022%2C%20the,nutrition%2C%20personal%20hygiene%20and%20medicine

[7] https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/healthcare-spending-versus-life-expectancy-by-country/

[8] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.624962/full

[9] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.624962/full

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62584/

[11] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.624962/full

[12] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022

[13] https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041219

[14] https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/clinical-services-and-systems/primary-care

[15] https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per-10-000-population)

[16] https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l2349

[17] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/tackling-healthcare-access-constraints/

[18] https://digital.nhs.uk/services/spine

[19] https://www.data4sdgs.org/sites/default/files/services_files/Kenya%20Health%20Information%20Systems%20Interoperability%20Framework.pdf

[20] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7612439/

[21] https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/808677

[22] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7259877/

[23] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[24] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2798115

[25] https://www.choosingwisely.org/

[26] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[27] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[28] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[29] https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/Reducing-Emergency-Admissions-long-term-conditions-briefing.pdf

[30] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[31] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[32] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[33] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/norway

[34] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly

[35] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

[36] Drug Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future, World Bank, 2017

[37] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[38] https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Tackling-Wasteful-Spending-on-Health-Highlights-revised.pdf

[39] https://www.valuehealthregionalissues.com/article/S2212-1099%2818%2930116-X/pdf

[40] https://www.jhpor.com/article/1312-drug-procurement-cooperation-lis—norwegian-tender-system-to-reduce-cost-of-expensive-medicines

[41] https://ti-health.org/content/the-ignored-pandemic/

[42] ‘Corruption in the health sector: A problem in need of a systems-thinking approach.’ Emily H. Glynn

[43] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617300837

[44] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/fact-sheet-health-care-fraud-and-abuse-control-program-protects-conusmers-and-taxpayers

[45] https://www.jstor.org/stable/45090768

[46] https://www.dlprog.org/publications/research-papers/islands-of-integrity-reductions-in-bribery-in-uganda-and-south-africa-and-lessons-for-anti-corruption-policy-and-practice

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit