Rising to the climate challenge

The climate crisis threatening our planet is so big, so serious and – seemingly – so intractable, it’s not surprising people sometimes feel helpless in the face of such an enormous challenge. But addressing the climate challenge, and all that this means, is one I feel passionately about.

By Fady Jameel, Deputy President & Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel

There are so many interconnected issues to consider and address that, in this article, I’ll start with a more generalized view and return to some of the detail of individual problems and paths to a solution in future articles.

With a swathe of worrying predictions of rising sea levels, soaring populations and runaway temperatures from credible organizations in every corner of the globe, it’s all too easy to empathize with those who say it is too late to change direction; that the planet will ‘correct’ itself in time; or that technology will provide an easier solution at some unspecified time in the future.

And yet, rather being despondent about such dire prognoses, I believe we should treat them as an inspiration. As a spark to push us all to do more, to act quicker, and to strengthen our resolve. Because such forecasts offer us something invaluable: unprecedented clarity of vision.

We now know, indisputably, the consequences of our behavior if we do not adapt our way of living; we know that our response cannot commence at some hypothetical point in the future, but must begin now; and we know that the ultimate goal of our journey is nothing less bold than a net-zero pollution planet.

In the face of such stark choices, what more motivation does one need?

Risks of inaction

The recent United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on ‘Global Warming of 1.5°C’[1] aims to strengthen “the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty” – something we can surely all get behind.

The report highlights the scale of pressures currently facing our environment.

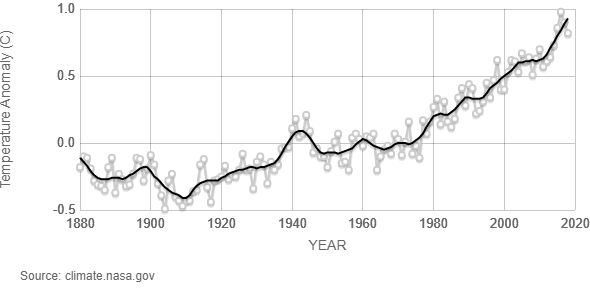

First, the bad news. Warming from existing human-centric emissions (in other words, those already generated) will persist over a time scale from centuries to millennia to come and continue to cause further long-term changes in the climate system. If it continues at the current rate, global warming is likely to reach at least 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 – and maybe more.

As the IPCC report makes clear, even a 1.5°C rise will hit humanity across the spectrum of basic needs, from health, livelihoods and food, to water supply, security and economic growth. Should temperatures instead rise by a quite plausible 2.0°C, that extra half degree is likely to add an additional 10cm to sea levels. It doesn’t sound much, but 10cm would be enough to trigger more extreme impacts on terrestrial, freshwater and coastal ecosystems, increasing ocean acidity while decreasing ocean oxygen levels, forever damaging marine biodiversity and fisheries.

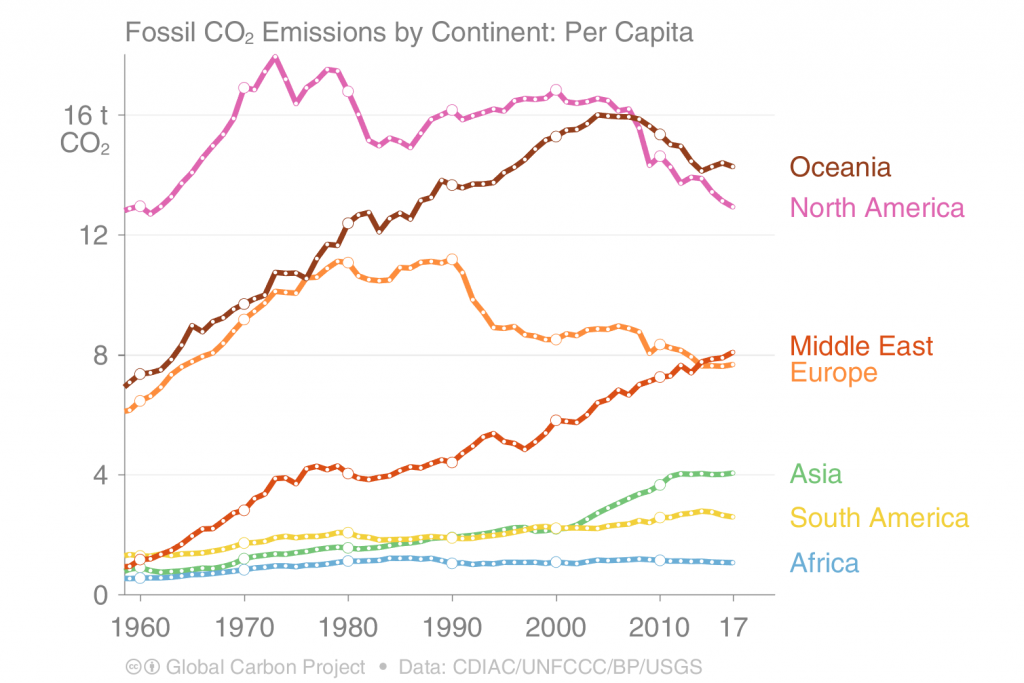

Even limiting temperature rises to ‘just’ 1.5°C will require dramatic intervention, with global CO2 emissions requiring a 45 per cent cut from 2010 levels by 2030, and by necessity reaching net-zero by 2050.

Achieving 1.5°C will, the IPCC notes, require “rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure and industrial systems” unparalleled in scale and incorporating deep CO2 reductions across all sectors. Tellingly, such a target also assumes large-scale adoption of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies capturing between 100 and 1,000 gigatons of CO2 throughout the remainder of the 21st Century.[2]

Data from NASA paints a similarly somber picture. In its report ‘The Effects of Climate Change’, NASA warns that the Arctic Ocean “is expected to become essentially ice free in summer before mid-century” and points to an eight-inch rise in global sea levels since reliable records began in 1880.[3]

Daunting, whichever way one looks at it. So, in practical terms, just what is to be done?

Solution One: Dealing with our existing carbon

CDR is rapidly establishing itself as a valid tactic for cutting greenhouse gases. CDR solutions span everything from the very high-tech (equipment that sucks CO2 straight from the air) to the notably low-tech (smarter land management).

Naturally, speed is of the essence, and a report from the US-based National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine suggests how we can fire some opening salvos in the battle.[4] Let’s start with the low-tech: and here nature is on our side, having provided us with a planet full of CO2 absorbers in our plants, trees and algae. Although hard to quantify precisely, three metric tons of CO2 can typically be absorbed by one acre of forest each year. Forestation as a whole, currently absorbs just under one third of our emissions. So, in short, we need to grow more trees to absorb more CO2 – a process called ‘offsetting’. We can also address our approach to rearing livestock. Letting animals graze over larger pastures, in contrast to intensive factory farming, helps aerate wider expanses of soil and encourages carbon-capturing grasslands.

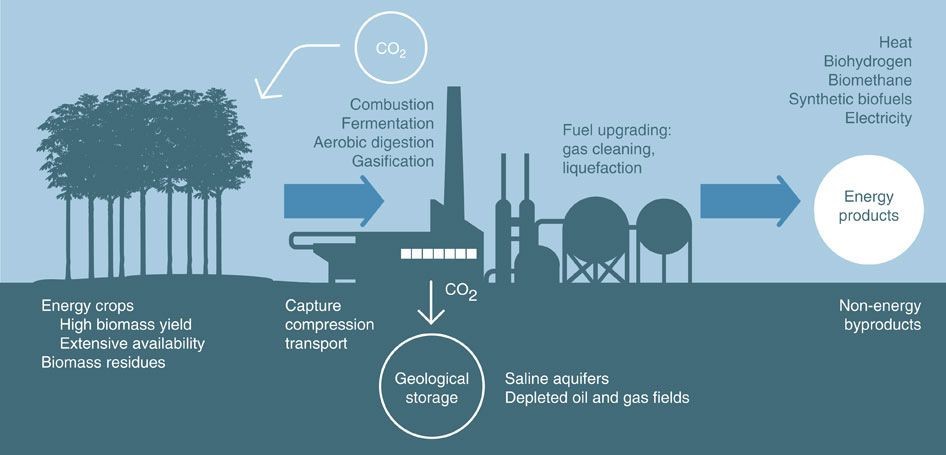

Inevitably, competition for land can constrain these natural remedies, but that’s not the end of the story. Biofuels represent a more high-tech natural answer and their benefits are twofold. Firstly, growing crops for fuel absorbs CO2 from the air. Secondly, when those crops are burned (for heat or power) at a bio-energy plant, the released CO2 can be permanently captured and stored. So-called ‘bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration’ (BECCS) schemes, however, require large areas of land to become truly game changing. Something that has limited their usage up to now.

Source: Nature Climate Change journal, volume 5, 2015

More nascent carbon-capture technology offers hope in the longer term. It’s incredibly challenging to artificially extract CO2 from the air. Despite its serious impact as a catalyst of climate change, CO2 represents just 0.04% of the atmosphere. Finding it, and trapping it, means sifting enormous amounts of air. But the technology to do this is improving all the time. A prototype plant now operating in Canada captures around one ton of CO2 daily. The company behind it, Carbon Engineering, has designed a similar, but much larger, plant in Texas that will capture around 5,000 kilotonnes annually, while a chain of three plants across Italy, Switzerland and Iceland collectively account for 1,200 tons annually. Making a sound economic case for capturing carbon will, of course, be crucial for its widespread endorsement. Here, the signs are good, with stored CO2 potentially being used in industry as methane fuels and fertilizers.

The concept of net-zero – where the amount of CO2 produced is balanced by the amount taken out of the atmosphere – is gradually moving from the realms of conjecture to reality.

In June this year, the UK became the first major world economy to pass legislation ending its contribution to global warming by 2050.[5] New rules will oblige the UK to render all greenhouse gas emissions net-zero by 2050, replacing a previous target of at least 80 per cent reduction from 1990 levels. Strategies will combine both offsetting and carbon capture. Payback could be tangible: the government anticipates the number of so-called ‘green collar jobs’ growing to two million by 2030, and the value of exports from the low carbon economy rising to £170 billion annually. Other countries will be watching closely.

Solution Two: Transitioning to a low carbon economy

Of course, the best way to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is limiting the amount we unnecessarily release in the first place. There is a vast and exciting movement under way to shift our economies to low carbon alternatives.

Notwithstanding the unfortunate withdrawal of the United States, the UN’s 2016 Paris Agreement still spearheads global efforts in this regard. Rewards can be sizable. As the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) observes in its 2018 report on a low carbon transition in the energy sector, successfully managing this shift has the potential to “reduce inequality, boost sustainable development and create new economic opportunities”.[6]

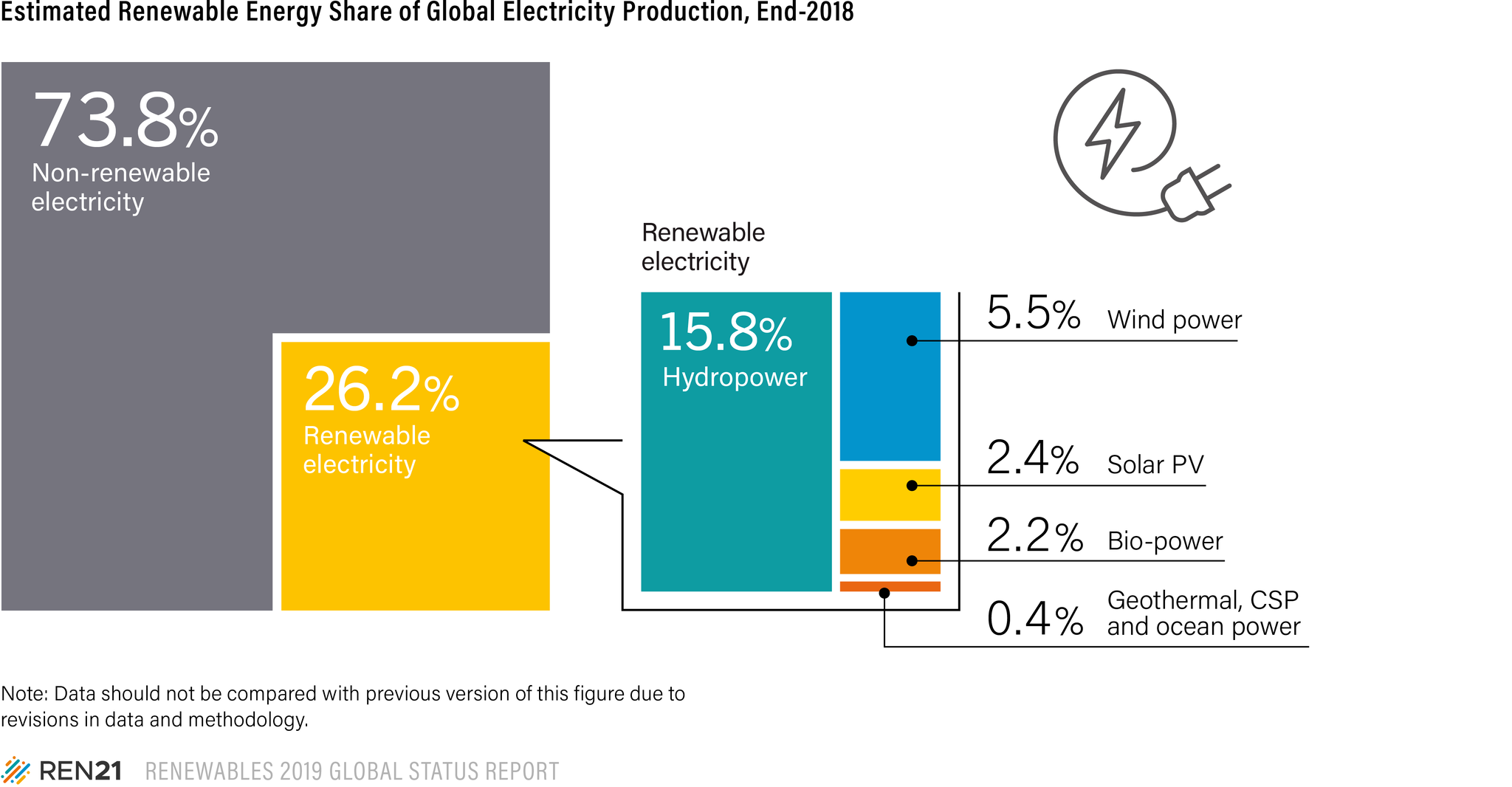

Promisingly, the global drive towards green energy continues to forge ahead. The Renewables 2019 Global Status Report[7] states that in 2018, a further US$ 289 billion of new investment was made globally in renewable power and fuels. In the power sector alone, renewable capacity leapt from 2,197 gigawatts in 2017, to 2,378 in 2018.[8]

Goldman Sachs, in its ‘Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy’ think-piece, states that a successful transition will require both public-private partnerships and international collaboration. Synergy between three key elements – policy, technology and capital – is imperative. Some US$ 10.5 trillion of investment in low carbon technology and energy efficiency will be needed by 2030 to limit temperature rises to 2.0°C, encompassing all sectors (power, transport, residential, commercial building, agriculture and industry). [9]

Putting the statistics aside, we need to accept that many countries, and their citizens, might struggle for stability amid such fundamental changes. One instructive voice on this subject is anthropologist and environmental historian Jared Diamond, whose recent book ‘Upheaval: How Nations Cope with Crisis and Change’ draws parallels between crises at personal and national level and finds common solutions.

If the crisis in this instance is global warming, Diamond argues there are several stages to responding effectively, including: accepting responsibility, garnering comprehensive support, modeling solutions from other nations, and rebuilding identity through honest self-appraisal and flexibility. Just as there are many examples of major nations having rebounded from significant crises (post-WW2 Germany and Japan among them) the world, similarly, already has the capability to respond from the climate peril and emerge stronger as a result. What continues to be needed is the will and policy direction to move into action.

Will such global thinking be essential to mitigate the effects of climate change? Undoubtedly, if ‘first’ and ‘developing’ worlds are to have equitable means of cleanly producing power for their societies; or if further environmental decline forces us to confront difficult issues such as border strife and migration.

“Nations and individuals accept national and individual responsibility to take action to solve the problem,” writes Jared Diamond, “or else deny responsibility by self-pity, blaming others, and assuming the role of victim.”

It’s clear to me which path we must choose in the climate crisis.

Investing in our shared future

At Abdul Latif Jameel, we recognize that a problem exists and that its scale is considerable – but we also take ownership of the problem by embedding it in our long-term mission.

Peak Power: 125.00 MWp, annual Production: 283,325 MWh/Year; CO2 Avoided: 175,000 t/Year, Households Supplied: 45,000 Homes, Area: 400.00 Hectares, Type: Single Axis Tracking System.

Through Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV), party of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy we are harnessing low carbon solutions such as wind and solar energy to generate clean energy across a growing global footprint.

In April this year we further expanded our active global solar portfolio by beginning power generation at two new sites: the Lilyvale Solar Plant in Queensland Australia (powering 45,000 homes while saving 175,000 tons of CO2 per year); and the Al Safawi Solar Plant in Jordan (a 150 hectare site powering 21,000 homes). Lilyvale is one of six Australian projects and Al Safawi one of three in Jordan. We’re currently constructing a 50 MW solar farm in Spain, too.

In tandem with solar, our wind projects continue to gather pace. In Chile, we’re developing our first hybrid solar-wind plant in a project that will power 224,000 homes and save 221,000 tons of CO2. We’re also active across other markets Latin America including Mexico and Uruguay, and continually assess opportunities in other countries.

In January, we entered the Japanese energy market with a project to install micro wind turbines that began with the initial two at Cape Erimo in Hokkaido. With a capacity of 20 KW each, these new installations will bring the total micro-turbines to be delivered through this project to 20: 6 units in Hokkaido, 12 in Aomori and 2 in Akita. Their combined power will generate a total of 400 KW into the national grid: enough to supply energy to around 400 typical homes and saving around 1,000 tons of CO2 annually through 20 year agreements with regional power companies Hokkaido Electric Power Company and Tohoku Electric Power Co., Inc. respectively.

It is a small step, but one that is a sure sign of our intent. In partnership with FRV, more than fifty further turbines will be added in the coming years.

We’re also determined to overcome one of the age-old problems of renewable energy – ensuring round-the-clock power in conditions dependent on the elements. That’s why, through FRV, we’ve this year launched a dedicated team to focus on the next generation of high-performance batteries, recognizing that power storage is critical to a dependable green energy future.

As anyone who understands our business knows, we’re also heavily invested in the global transportation market, and here too we’re favoring the greener route to success.

We’re the longstanding distributor in Saudi Arabia of Toyota and Lexus cars.

We’re the longstanding distributor in Saudi Arabia of Toyota and Lexus cars.

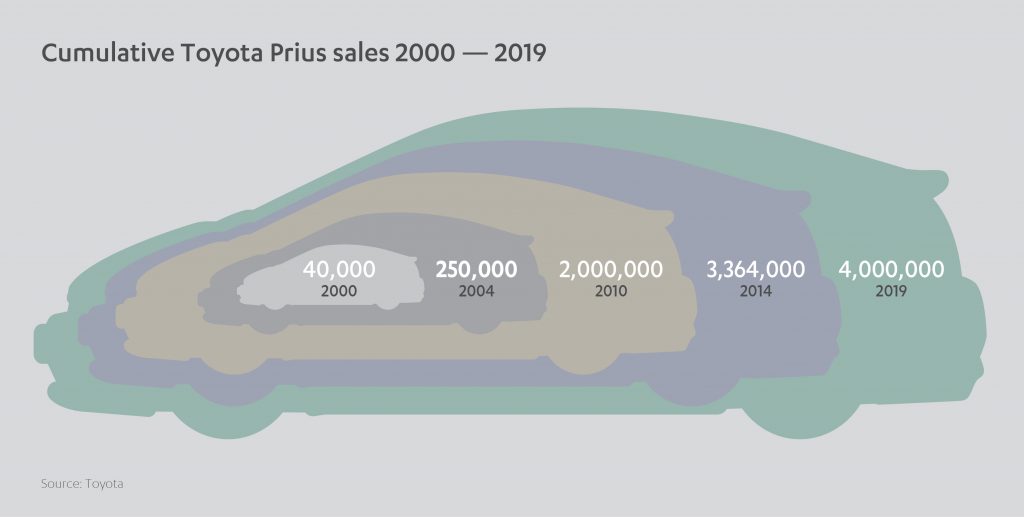

Toyota is widely acknowledged as the market leader in hybrid electric vehicles (HEV), with its landmark Prius model being the world’s bestselling hybrid, and the Toyota Mirai fuel-cell vehicle pioneering the hydrogen vehicle segment.

We were also an early investor in Michigan-based electric vehicle (EV) start-up RIVIAN, followed by major names such as Amazon, Ford Motor Co., and Cox Automotive.

RIVIAN unveiled its first two high-performance adventure models last year at the LA Auto Show and is working toward production start in 2020.

As sales of EVs continue to surge, the numbers suggest we’re heading in the right direction.

Global plug-in vehicle sales reached 1.1 million units in the first half of 2019, 46 per cent higher than for 2018.

Title: The surge in electric vehicle sales

Source: EV volumes, September 2019

With all this momentum, there’s no excuse for standing still. Our funding of four research labs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) includes J-WAFS, the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab. Since its foundation in 2014, J-WAFS has been seeking answers to the world’s water and food needs to combat the unprecedented challenges of climate change, population growth, urbanization and development. The lab employs cutting-edge technologies and programs to make a measurable international impact as humankind is forced to adapt to a fast-changing planet.

If ground-breaking action is needed – let’s break new ground

All evidence suggests that our environment is evolving quicker than seemed imaginable even a few years ago.

The empowering news is that the potential to change things for the better rests with us. The specter of failure is too ominous to accept.

Instead, we must see it as an opportunity.

An opportunity not just to improve the experience of life on Earth, but to unite people of all nations, backgrounds, beliefs and skills behind a common cause – recognizing our universal vulnerability and our collective capacity for transformation.

We recognize our pivotal role in making a more sustainable world. It’s a journey we’re on together.

[2] https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Headline-statements.pdf

[3] https://climate.nasa.gov/effects/

[4] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25259

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-becomes-first-major-economy-to-pass-net-zero-emissions-law

[6] https://www.sustainablefinance.hsbc.com/reports/enabling-a-just-transition-to-a-low-carbon-economy-in-the-energy-sector

[7] https://www.ren21.net/gsr-2019/

[8] http://www.ren21.net/gsr-2019/

[9] https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/archive/archive-pdfs/trans-low-carbon-econ.pdf

Added to press kit

Added to press kit