Where next for mobility?

Turn back the clock a mere 50 years and the global mobility picture would be barely recognizable from today’s: among a global population of 3.7 billion people, only 30 million new cars and trucks were produced annually, and just 310 million passengers were carried in the air.

Jump forward to now, and while the world’s population has doubled, the number of new vehicles produced has increased three-fold to almost 100 million per year, and the number of air passengers has increased by more than 10 times to 4 billion.[1], [2]

With more people on the planet than ever before, it is no surprise that the demand for mobility has increased – and will continue to do so as global population levels and living standards continue to rise. But it is not only in terms of demand that today’s mobility model looks very different to that of 1969.

Fifty years ago, for most people, the mobility options had not changed much for decades. Mobility generally meant a motor vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine, a train or possibly a ship. Air travel was largely the preserve of the wealthy. City transport policies, such as they were, tended to prioritize getting as many motor vehicles into and around the city as quickly as possible.

In recent years, however, the expectations, models and technologies around global mobility have all undergone dramatic changes. Today’s transport planners and civic leaders across Europe, North America, the Middle East and elsewhere are more likely to be banning traditional motor cars from their cities than encouraging them. The mayors of Paris, Madrid, Mexico City and Athens, for example, have said they plan to ban the most polluting diesel vehicles from their city centers by 2025.[3]

This pace of change looks set to accelerate even further in the coming decades as our society looks for ever faster, cleaner and more efficient ways to move large numbers of people and goods around the planet.

Understanding how new mobility systems will operate in the future – and the technology underpinning them – can help shed light on the opportunities and challenges that face us. Anticipating these changes will help drive the economy, protect the environment and safeguard societies, but planning how best to address them needs to start now.

Car ownership booms despite bumpy roads

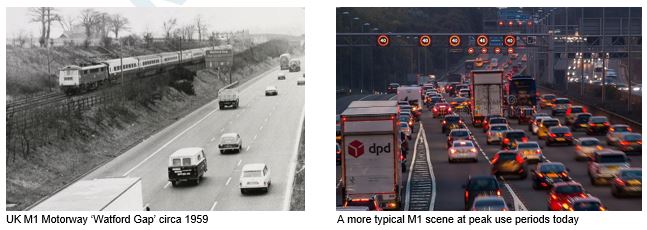

On the face of it, the long term prospects for the traditional motor vehicle do not look good. City roads are progressively more congested, leaving drivers stranded behind their wheels when they could be working or enjoying private leisure time. With average city density tipped to increase by 30 per cent over the next 15 years,[4] many conurbations around the world are maxing out their infrastructure scope – there’s little physical space for more roads, leaving ever-more vehicles funneled on to existing routes.

Research by traffic information company Inrix[5] shows that drivers are spending an average of 73 hours a year stuck in traffic jams in London – ranked the seventh worst city in the world for congestion, while the UK as a whole is ranked the third worst traffic congestion nation in Europe, with some drivers spending up to 32 hours a year in traffic, equating to around £31 billion (US$ 38.6 bn) in opportunity cost.

Data published last year by Transport for London revealed that the average bus speed on many routes was under 5 miles per hour – significantly slower than an average donkey! It is a similar situation in Hong Kong, where the average speed on some central roads is less than 6 miles per hour, according to a 2015, government report.[6]

Then there’s the no small matter of pollution. According to the UN Environment Program, the transport sector is the fastest growing contributor to climate emissions. Particles from cars and other vehicles – including black carbon and nitrogen dioxide – also contribute to a range of illnesses including respiratory conditions, strokes, heart attacks, dementia and diabetes[7].

In the United States, cars and trucks account for nearly one-fifth of all US emissions, while the transportation sector as a whole – which includes cars, trucks, planes, trains, ships, and freight, produces nearly 30 per cent of all US global warming emissions – more than almost any other sector.[8] So any steps to reduce emissions from the transport fleet will bring exponential benefits for emissions and air quality.

Air pollution causes an estimated 40,000 early deaths in the UK every year. The British government, (which has lost three court cases over air quality since 2015), plans to ban new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2040 as part of a £3 billion (US$ 3.9 billion) clean air strategy.

They are not alone.

France has also pledged to end the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles by 2040, whilst Denmark has proposed a full ban on new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 and even on hybrid vehicles from 2035.[9]

Although data varies, many scientific studies predict that without remedial action, a rise in average global temperatures of several degrees by the end of the century is realistic. And if the Paris Climate Agreement targets are not met, up to a quarter of the world could experience drought by 2050.[10]

Dwindling fossil fuel supplies cast a further shadow over the longevity of the current generation of cars and trucks. Based on known reserves and annual production levels, oil and natural gas could run out in as little as 50 years.[11]

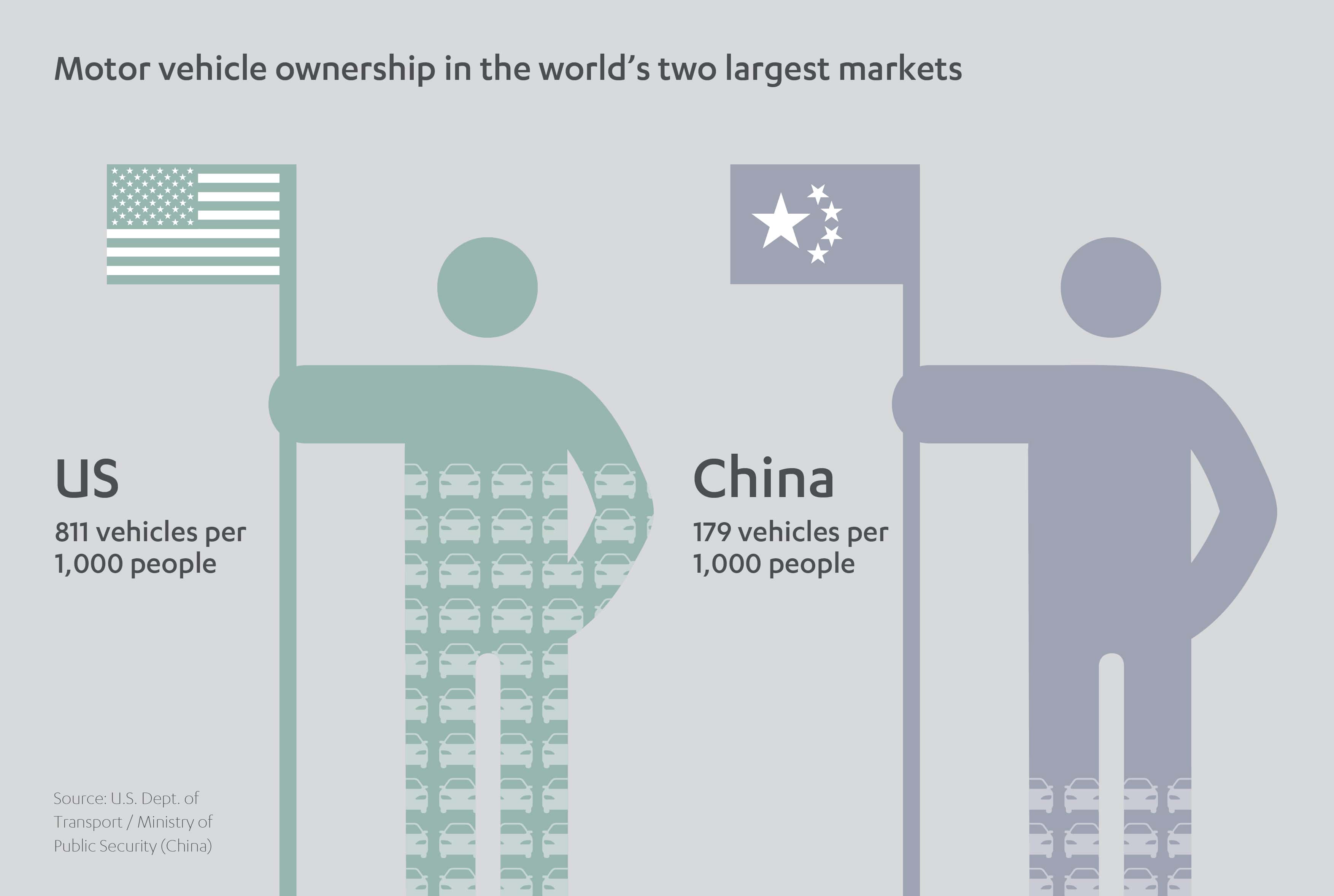

Yet despite these drawbacks and limitations, the motor vehicle is proving resilient. Two countries alone, the USA and China, account for almost a half-billion vehicles in operation[12]; the difference in per capita ownership between the two countries (857 vehicles per 1,000 people in the USA, compared to just 155 per 1,000 in China) suggests that with the Asian economy continuing a positive growth trajectory, the expansion in vehicle ownership in China still has a long way to go. In Saudi Arabia, itself a fast-growing economy, registered motor vehicles hit 6.6 million as recently as 2015, having doubled from the previous decade.[13]

While the concept of the ‘private vehicle’ may be with us for some years yet, then, the nature of that vehicle – and the way it interacts with the wider transport picture – is one of the areas expected to see the biggest changes in future mobility systems.

Vehicular visions of the (near) future

Global management consultancy McKinsey believes many urban areas will undergo a mobility revolution driven by the growth of megacities, the emergence of business disruptors such as Uber and China’s Didi Chuxing, and electrification. In its report, ‘An integrated perspective on the future of mobility’[14], McKinsey says that while the changes will vary globally, they will generally be based around one of three models:

- Clean and shared applies to high-population metropolitan areas in developing countries from Mexico to India, where poor infrastructure and haphazard road behavior could limit the continued rise of self-drive internal combustion engine cars. Instead, hybrid and electric vehicles (EV) will come to the fore, along with shared ownership, ride hailing and an expanded public transport system. By 2030, McKinsey believes shared vehicles could account for around 50 per cent of journeys in many Asian cities.

- Private autonomy will affect more developed economies such as the United States where urban sprawl has made car ownership vital. This will lead to the rise not just of EVs in ever connected ‘smart cities’ packed with convenient (and rapid) charge stations, but also self-drive autonomous AI vehicles. A large number of these were unveiled at the recent Frankfurt IAA motoshow.

- The seamless mobility system is most likely to surface in wealthy, densely-populated cities like London and Singapore, where private, shared and public transport integrate in streamlined fashion, all managed by smart software platforms.

Making the case for electrification, McKinsey notes that “the costs of a lithium-ion battery pack fell 65 per cent from 2010 to 2015 and they are expected to drop below US$ 100 per kilowatt-hour over the next decade”.

These changes are already having an impact. Data from EV volumes, the electric vehicles world sales database, reveals that over 1.1 million plug-in electric vehicles were sold during the first half of 2019, 46 per cent higher than the same period in 2018. This includes all battery-powered and plug-in hybrids (PHEV) passenger cars sales, light trucks in the Americas and light commercial vehicle in Europe and Asia. The data shows that 74 per cent of sales were battery powered and 26 per cent were PHEVs, a shift of 11 per cent towards batteries compared to the same period in 2018[15].

The McKinsey report urges collaboration towards shared goals by private and public sectors. Governments and innovators should be aware how the success of some aspects of a model (for example, self-drive cars or sharing schemes) could counteract others, such as public transport.

Public transport, in fact, is one area where electrification is already picking up pace across the globe. In 2017, the Chinese city of Shenzhen said all of its more than 16,000 buses had gone electric, giving it the world’s first 100 per cent electrified bus fleet. In Germany, Siemens worked with bus operators to provide re-charging stations for models from different manufacturers, a key step in ensuring interoperability.[16]

Similarly, in Adelaide, Australia, city authorities introduced the world’s first electric solar-powered bus in 2013, while London plans to add 68 new zero-emission double-decker buses to its fleet in 2019, bringing the total number of electric buses in the city to 240. By 2037, all buses in London will be zero-emission, authorities say.[17]

Despite these new models of public mobility, however, the rise of urban e-scooters and hire bikes indicates that demand for single-person vehicles is far from waning. Industry experts at Deloitte highlight such ‘micromobility’ as having the potential to join-up disparate public transport networks, cut reliance on private cars, and reduce greenhouse gases.

Despite these new models of public mobility, however, the rise of urban e-scooters and hire bikes indicates that demand for single-person vehicles is far from waning. Industry experts at Deloitte highlight such ‘micromobility’ as having the potential to join-up disparate public transport networks, cut reliance on private cars, and reduce greenhouse gases.

Growth has been rapid.

E-scooter rental service Bird, Deloitte notes, notched up 10 million rides in its first year in California, while Lime’s range of e-scooters, e-bikes, and car-shares recorded 34 million journeys in a similar timeframe.[18]

Naturally, micromobility arrives with its own set of challenges: vandalism and theft, the cost of retrieving and recharging units, their unsuitability for commercial transportation, and alignment with government policies (such as safety or rights-of-way).

Again, the private and public sectors must work in harmony to ensure early enthusiasm continues and micromobility doesn’t disappear beneath red tape and regulations. Deloitte predicts that, via micromobility, “trailblazing cities have a real opportunity to transcend the limits of existing infrastructure and forge a new approach to governing the future mobility ecosystem”.

Taken together, these technologies could slot into a broader landscape of greener air travel (electrically powered aircraft are being tested today and some flights might even become solar-powered[19]) and eco-trains (in September 2018, the world’s first commercial hydrogen-powered passenger train entered service in Lower Saxony, Germany[20]) to usher in a future of cleaner, safer and faster journeys for all.

Uniquely placed to capitalize on golden opportunities

If the future of personal mobility is electrification, few countries are better positioned to prosper than those in the Middle East. Long hours of intense sunshine, affordable labor and plenty of wide open spaces enable the region to produce an increasing amount of electricity by solar power.

Saudi Arabia alone is planning an extra 9.5 GW of green energy in the coming decade. Jordan and Egypt are likewise securing financial backing from international banks for photovoltaic projects. Research consultancy Wood Mackenzie recognizes the fastest movers in the PV market as all being concentrated around the Middle East and Mediterranean (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt and Italy).[21]

The relative ‘youth’ of many Middle Eastern cities is also advantageous. Speaking at the fourth International Conference on Future Mobility in Abu Dhabi 2018, Christian Drakulic, Director of Innovation at the Austrian Ministry of Transport, Innovation, and Technology, earmarked the UAE as an early adopter of AI in future mobility systems.

“Compared to Europe, the UAE doesn’t have long-lasting history in transport infrastructure, yet this might turn out as an advantage since the country doesn’t need to consider an ‘old heritage’ with stranded investments and technically determined mobility patterns,” said Drakulic. “It seems viable for the UAE to leapfrog some technological development stages and directly kick-off the launch of novel mobility solutions, making full use of AI as an enabling technology.”[22]

The key, some argue, isn’t necessarily in owning individual mobility assets. Rather, it’s in controlling the digital platform that unites these various modes of transportation. This not only allows traffic flow to be managed, but also allows commuters to access transport information via a single, real-time and easy-to-use interface.

Any future road networks in the Middle East will need to tackle the challenges of congestion and safety, both areas where this rapidly mobilizing region trails the developed world. In Dubai, for example, an average trip takes 29 per cent longer than it would in uncongested periods, compared to 20 per cent in the West.[23] Road deaths also need combating via more traffic calming and enforcement; the UAE has 18.1 fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants per year, Saudi Arabia 27.4, and Oman 25.4, as opposed to just 3.1 in the UK.[24]

Particularly in the Middle East, it will prove imperative to view transport systems in an integrated rather than individual manner. In hot climates, where walking and cycling are less viable options for extended periods of the day, particularly in summer months, public transport systems must –wherever possible – mimic a door-to-door solution. If trips are joined-up and seamless, they will automatically become popular.

The region is bursting with vision and foresight. Dubai’s Autonomous Transportation Strategy aims to transform 25 per cent of total transportation in Dubai to autonomous mode by 2030, involving five million daily trips and saving AED 22 billion in annual economic costs.[25] Similarly in Riyadh, the government is investing billions of dollars in a new transport system that will integrate metro, bus and bus rapid transit systems across the city.

Towards a new kind of mobility

Passionate about supporting a sustainable environment for future generations, Abdul Latif Jameel, too, is making its own contribution towards cleaner, more efficient mobility systems.

An influential player in key sectors throughout the Middle East and North Africa region and beyond, it recognizes the significance of sustainable and efficient transport options for flourishing communities. Planning for the movement of people and goods is as critical as planning for housing, education and health, and feeds into all these sectors, too.

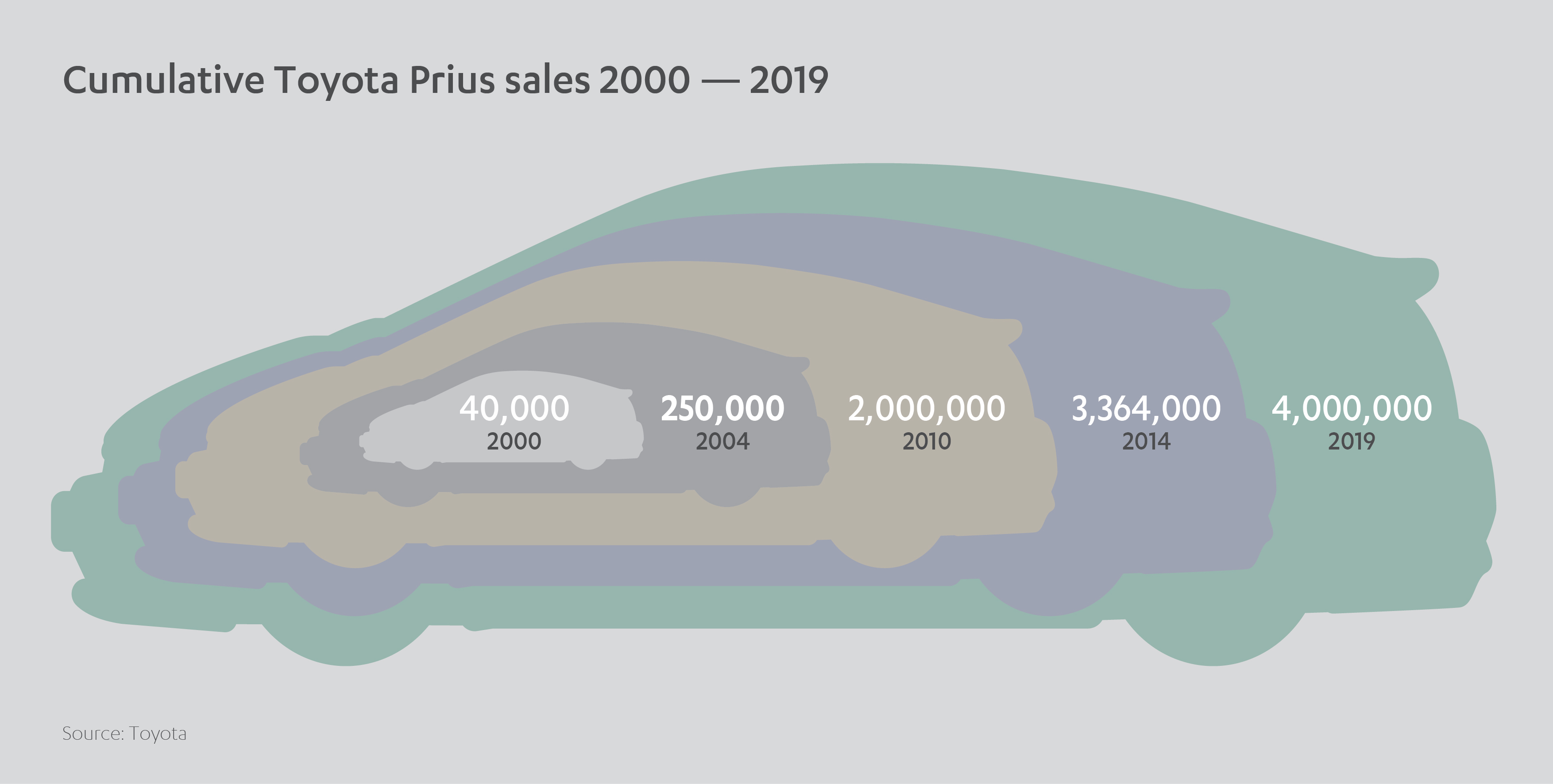

Abdul Latif Jameel has been Toyota’s distributor in a number of key markets for many years (Saudi Arabia since 1955). Toyota itself is at the forefront of the move towards greener, more efficient motor vehicles. It is the world market leader in hybrid electric vehicle (HEV) sales, and the first to mass produce such cars as the Toyota Prius in 1997, now the world’s top-selling hybrid with sales of over 4 million.

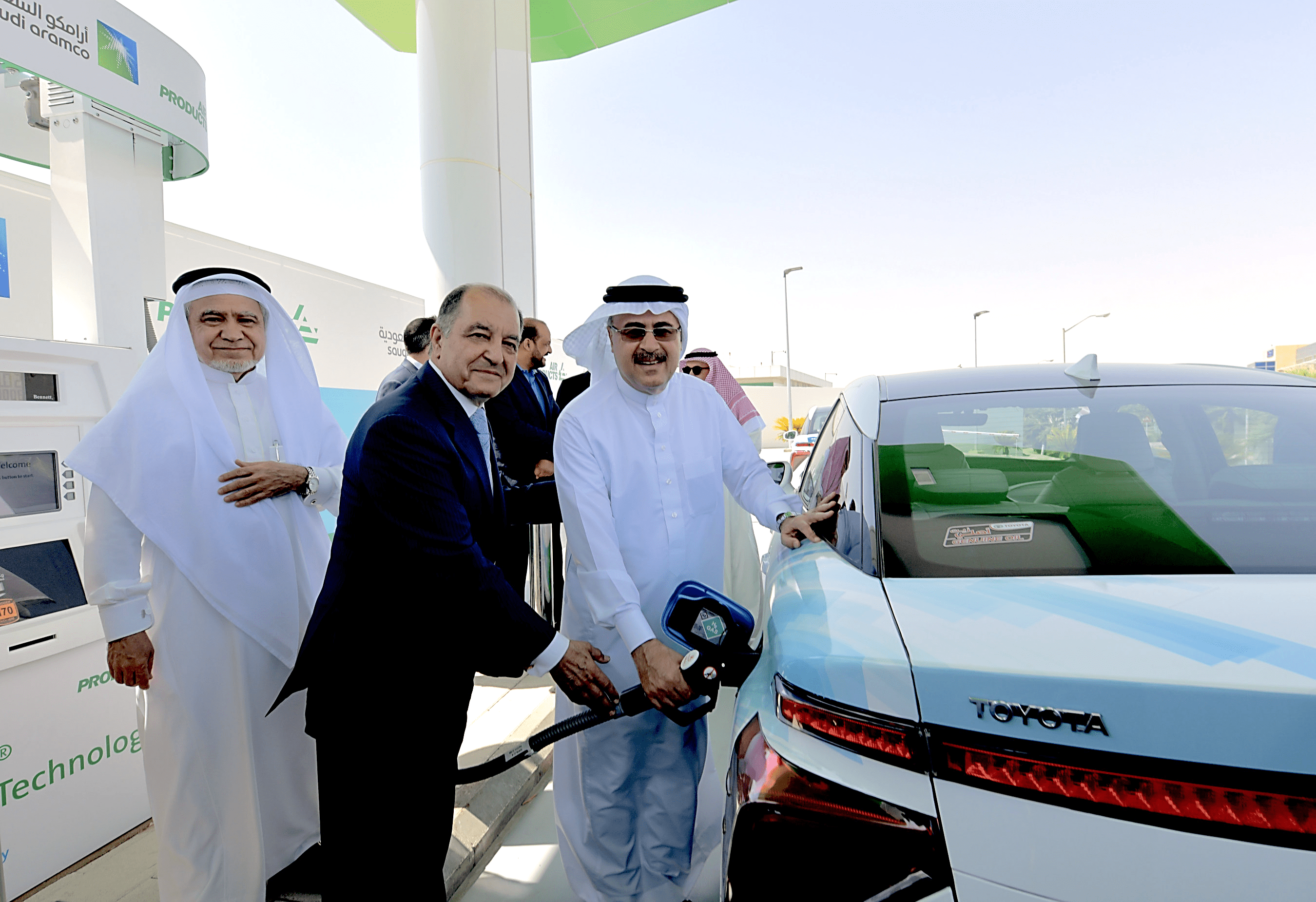

Toyota’s leadership and innovation at the cutting edge of environmental mobility solutions does not stop there. It has been researching and developing hydrogen fuel cell vehicles since the early 2000s, and in 2014 it unveiled the Mirai, a zero-emission hydrogen fuel cell vehicle that runs on compressed hydrogen gas and emits only water.

Toyota’s leadership and innovation at the cutting edge of environmental mobility solutions does not stop there. It has been researching and developing hydrogen fuel cell vehicles since the early 2000s, and in 2014 it unveiled the Mirai, a zero-emission hydrogen fuel cell vehicle that runs on compressed hydrogen gas and emits only water.

Abdul Latif Jameel recently supplied a test fleet of Mirai vehicles for a pilot project between Saudi Aramco and Air Products, opening Saudi Arabia’s first hydrogen vehicle fueling station in the Dhahran Techno Valley Science Park.

Raad Al Saady, of Abdul Latif Jameel, described hydrogen as a “clean and sustainable fuel that offers drivers the same five minute gas station fueling experience with a much higher ranger compared to electric vehicles”.[26]

Raad Al Saady, of Abdul Latif Jameel, described hydrogen as a “clean and sustainable fuel that offers drivers the same five minute gas station fueling experience with a much higher ranger compared to electric vehicles”.[26]

Further demonstrating its commitment to a more sustainable future mobility model, Abdul Latif Jameel is a primary investor in RIVIAN, a fast-growing US-based EV and mobility firm. Other investors in RIVIAN include, the retail giant Amazon who led a US$ 700m funding round in the company and US$ 500 million from Ford Motor Company followed most recently by a further US$ 350 million from Cox Automotive.

The CEO of Amazon’s Worldwide Consumer division, Jeff Wilke, said Amazon was “inspired by RIVIAN’s vision for the future of electric transportation” and in announcing their intention to make the giant carbon neutral by 2040, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos kicked this off with an order of 100,000 electric delivery vehicles from RIVIAN with 10,000 to be on the road by 2022 and all 100,000 by 2030, “saving 4 million metric tons of carbon per year by 2030”.

RIVIAN unveiled its first two models, an electric pickup truck (R1T) and an electric SUV (R1S), at the LA Auto Show in November 2018, targeted at 2020 production start. The vehicles are classed as ‘Level 3 Autonomous’ – meaning drivers’ eyes can safely be taken off the road – and are predicted to redefine performance for electric cars. The RIVIAN truck, for example, can achieve 0-97km/h in three seconds, safely traversing 1.1m of water and climbing a 45 degree incline. Top-end models could boast a 725 km range on a single charge.

As exciting as these advances are, however, the future of mobility is not about any one individual product, system or brand. The watchword on the lips of governments, researchers, technologists and planners is ‘integration’.

Of course, specific technologies like electric or hydrogen vehicles, electric buses, e-scooters or autonomous metros will be a key part of tomorrow’s mobility landscape, but only by connecting these different nodes together into joined-up, easy-to-use, efficient integrated mobility systems can long term change be achieved and decades of behavior and public perceptions changed.

As Deloitte states in its Governments and the future of mobility report[27], “creating and maintaining a new mobility ecosystem will require rethinking traditional ways of doing business”.

This is a challenge that touches every community on our planet. But innovative investment on a global scale is the cornerstone of Abdul Latif Jameel’s approach to business. Through its continued investment in the ‘infrastructure of life’ in key markets around the world, from transport to energy, e-commerce to real estate, Abdul Latif Jameel is committed to supporting a new approach to mobility that can help to deliver a cleaner, greener future for all.

[1] https://www.bts.gov/bts/archive/publications/national_transportation_statistics/table_01_23

[2] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.AIR.PSGR?end=2017&start=1970

[3] Gearing up for change: transport sector feels the heat over emissions

[4] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/an-integrated-perspective-on-the-future-of-mobility

[5] http://inrix.com/scorecard/

[6] https://www.erp.gov.hk/download/PEReport_full_EN.pdf

[7] Gearing up for change: transport sector feels the heat over emissions

[8] https://www.ucsusa.org/clean-vehicles/car-emissions-and-global-warming

[9] Gearing up for change: transport sector feels the heat over emissions

[10] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-017-0034-4

[11] https://ourworldindata.org/how-long-before-we-run-out-of-fossil-fuels#note-6

[12] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackperkowski/2018/11/27/will-2018-be-an-inflection-point-for-chinas-auto-sales/#5d5b30983ed1

[13] https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/saudi-arabia/motor-vehicle-registered

[14] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/an-integrated-perspective-on-the-future-of-mobility

[15] http://www.ev-volumes.com/news/81958/

[16] Gearing up for change: transport sector feels the heat over emissions

[17] https://www.intelligenttransport.com/transport-news/87086/the-london-electric-bus-fleet-is-the-largest-in-europe/

[18] https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/future-of-mobility/micro-mobility-is-the-future-of-urban-transportation.html

[19] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/26/solar-impulse-plane-makes-history-completing-round-the-world-trip

[20] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/sep/17/germany-launches-worlds-first-hydrogen-powered-train

[21] https://www.woodmac.com/news/editorial/10-trends-shaping-the-global-solar-market-in-2019

[23] https://www.newmobility.global/future-transportation/urban-mobility-growth-leading-example-middle-east/

[24] Global status report on road safety 2018, WHO, 2018.

[25] Dubai World Congress for Self-Driving Transport

[26] https://alj.com/en/news/saudi-aramco-air-products-build-saudi-arabias-first-hydrogen-fuel-cell-vehicle-fueling-station/

[27] https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/future-of-mobility/government-and-the-future-of-mobility.html

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit