Decarbonization begins at home

A substantial proportion of greenhouse gas emissions are generated by individuals and households – can we make the changes needed to reduce them?

When thinking about the challenges of meeting net zero, we often look at the actions being taken by industries and politicians. But individual households are a significant contributor to emissions. Can we play a bigger role in decarbonization?

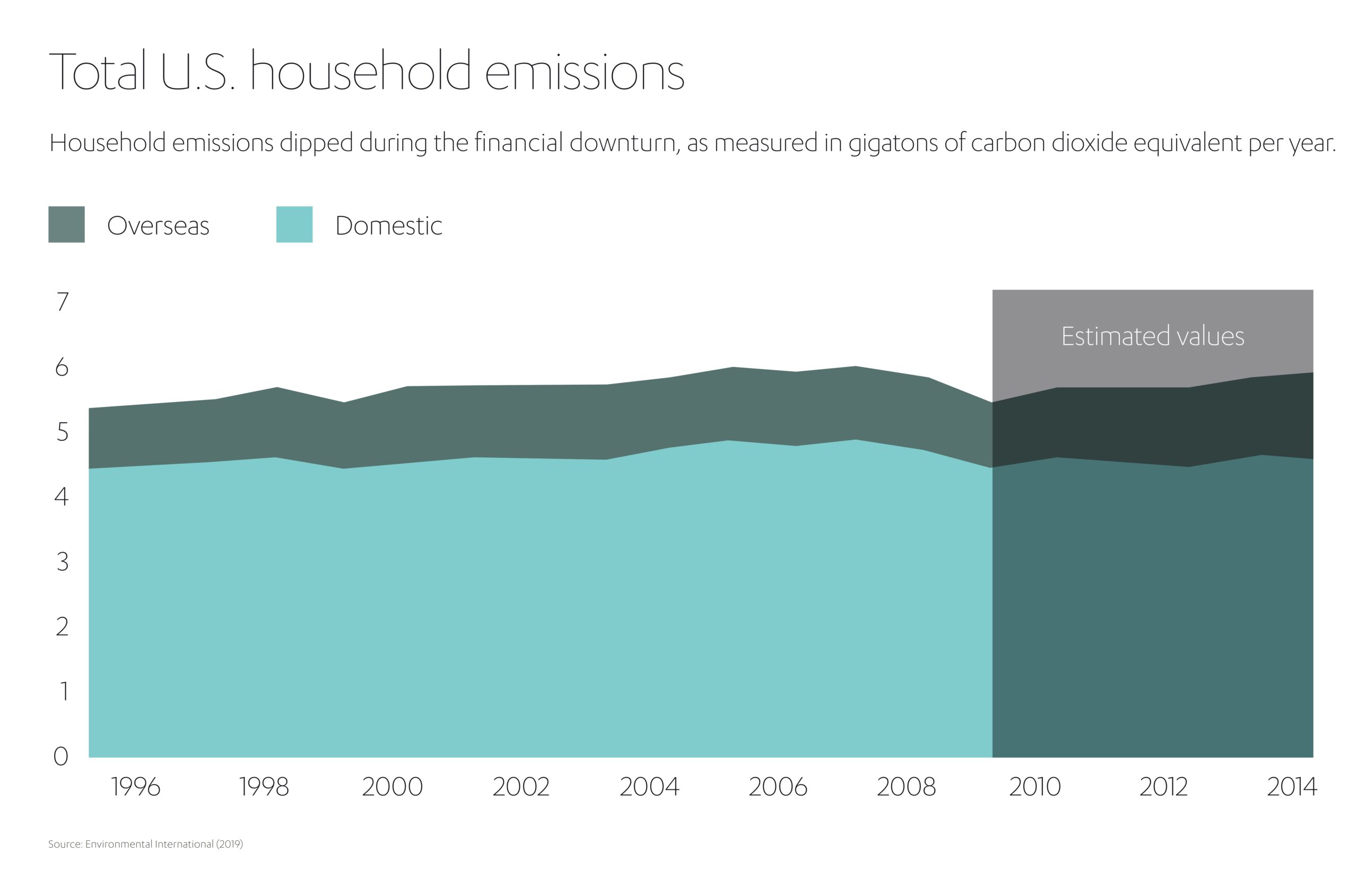

Researchers from the US have found that about 20% of greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed directly to households. This is mainly due to the use of fuel – for purposes including running private vehicles as well as heating, cooling and cooking[1]. The most recent data indicates that 59% of US households still rely on fossil fuels for their main heating – with just over half of homes (51%) using natural gas[2]. Emission-heavy fuels are also used extensively in European homes. In 2022, natural gas accounted for almost a third (30.9%) of energy consumption in EU households, with a further 10.9% down to oil and petroleum products. In the EU, almost two thirds of household energy use is accounted for heating buildings (63.5%), with a further 14.9% used for heating water.

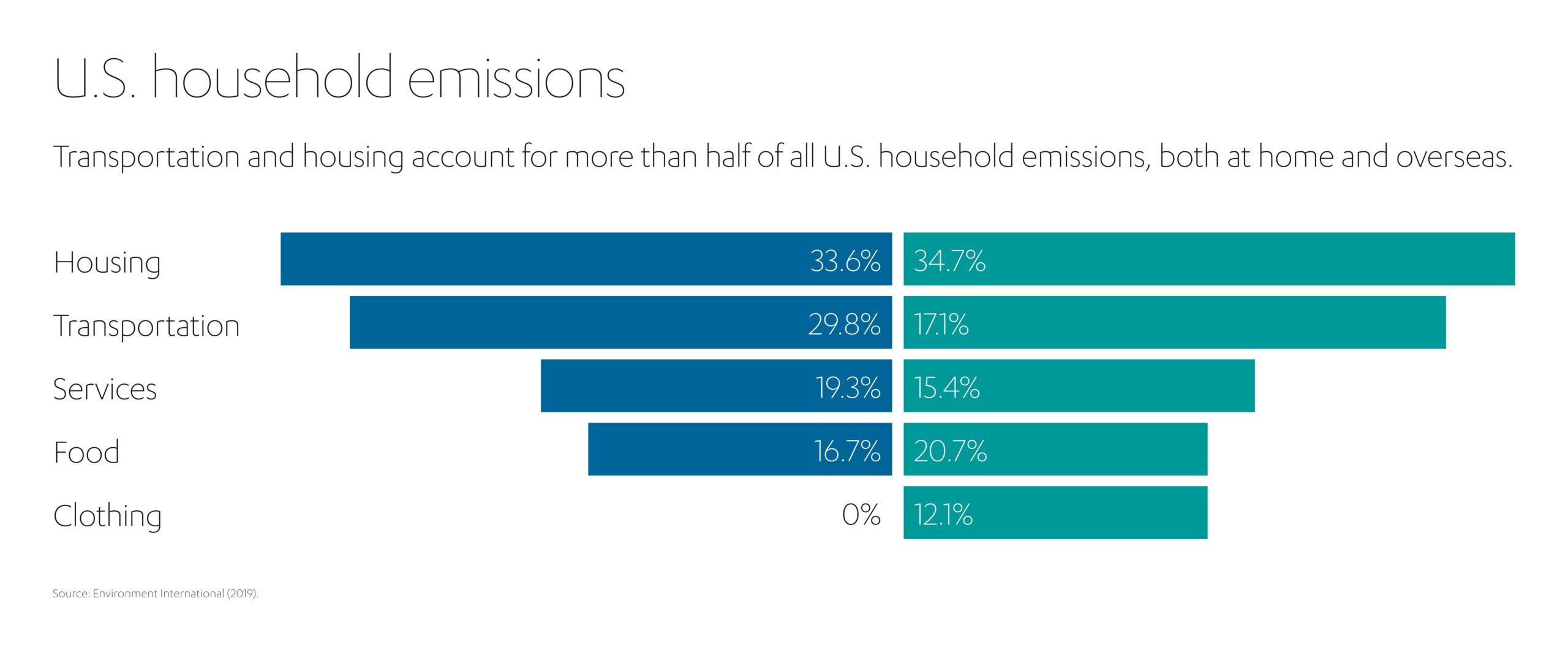

Being responsible for one fifth of greenhouse gas emissions is substantial. But the impact of households is even more significant when we also consider indirect emissions: the emissions that the consumption of goods and services creates in the supply chain. For example, although wearing clothes doesn’t emit any carbon directly, emissions are generated in the processes used to make them and provide them to consumers. Similar principles apply to most other ‘household’ categories, such as food, entertainment and public transport. Little wonder, then, that the combined direct and indirect impact of household consumption accounted for about 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions[3], often in countries far from where the end-products are actually consumed.

More than a quarter (27%) of US households’ overseas carbon footprint is generated in China – with Canada, India, Russia and Mexico also contributing significant proportions. Looking at different types of household consumption, about 70% to 85% of the carbon footprint of clothes bought by US households is produced overseas, along with about two-thirds (65%) of emissions driven by spending on electronics.

Overall, wealthier households are responsible for more emissions: although households earning more than US$ 100,000 a year comprised less than a quarter (22.3%) of the total population, they accounted for almost one third of households’ overall carbon footprint.

Potential for households and individuals to contribute

Given domestic life accounts for a considerable proportion of emissions both directly and indirectly, changing our behavior has the potential to make a significant contribution to net zero efforts. The Project Drawdown NGO explains that while most emissions are directly dependent on powerful decision-makers in business, government and elsewhere, “our choices as consumers, energy users, tenants, and voters have direct impact in their own right and can affect those decisions by sending signals across the system”.

According to an analysis by Project Drawdown, actions by individuals and households could potentially bring about more than a quarter of the total emissions reductions needed to stop global temperatures rising beyond dangerous levels[4].

The highest-impact actions identified by the organization are adopting plant-rich diets and cutting food waste, with other top recommendations including installing solar panels, adequate insulation and LED lighting in homes.

Aside from the direct impact of these actions themselves, Project Drawdown stresses that they can also contribute to developing momentum by making them more appealing and accessible to others. “If you are able to install solar panels on your home,” for example, “you will inspire your neighbors to do the same and will put your local electricity provider on notice that citizens want to get their power from renewable sources instead of fossil fuels.”

Challenges of implementation

So, in theory at least, there is clearly much scope for actions by individuals and households to contribute to reducing emissions. But it isn’t a simple matter and looking at one important area – housing – can help us understand both the potential and the challenges.

There are many ways in which homes can be more energy efficient: they can be built from greener materials, be better insulated, or use less carbon-intensive heating methods, for example. Some of the approaches that could help rely on innovative technologies. Hydrogen boilers, for example, offer a much more climate-friendly way of heating homes. But the use of hydrogen as a fuel is still at a prototype stage (though there have been successful pilots in some places). In contrast, heat pumps – which act as ‘reverse fridges’[5], using heat from the air in the ground or the air to heat homes – are an established technology that is ready to use. As with insulation, the challenges with implementing it are not technological – they’re to do with practicalities and cost.

The International Energy Agency, for example, describes heat pumps as “the key technology to make heating more secure and sustainable”, saying they have the potential to reduce global CO2 emissions by at least 500 million tons in 2030.[6] Nevertheless, some efforts to encourage their adoption have met resistance. In Germany in 2023, the government passed a law that will make heat pumps the default source of heating buildings in future years by effectively banning new installations of oil and gas heating systems. But the measures were met with vociferous protests from the media[7] and political opponents, who argued they would damage prosperity. They created major tensions in Germany’s ruling coalition, as one government party also spoke out strongly against the plans[8]. The controversy contributed to the country being set to miss its targets for heat pump sales in 2024[9].

Complexities of changing behavior

Germany’s experience is being viewed with alarm in other European countries. It illustrates how, even when greener approaches exist, getting people to adopt them can be a major challenge. An international study in 2019 found that people’s living situations can limit their ability to reduce their carbon footprint[10] – giving the example of people renting their homes, who do not have the ability to make efficiency improvements. The researchers also found that people’s carbon footprint can change according to their life circumstances: having children or living with a health condition can make a significant impact, for example. Most concerningly, the research found that “the greater the mitigation potential of an action, the less willing are households to implement them”. About one third of participants, for example, said they would be happy to buy a more eco-friendly car to reduce their carbon footprint – but only 4% would be willing to completely give up their existing conventional vehicle.

In some cases, trends in consumer behavior can even negate the impact of technological and regulatory improvements. Research from 2019, on emissions generated by US households, for example, found that even though cars have become more efficient, transportation emissions have risen over the past two decades – despite “significantly reduced tailpipe emissions” and improvement in cars’ fuel economy by nearly a third[11]. These sustainability improvements were attributed to regulatory changes at the state and federal level. But the researchers said that emissions had nonetheless continued to increase, due to factors including a growth in ownership of household vehicles, and people’s desire to travel more.

Barriers to behavior change

There are clearly a number of barriers to consumers making the necessary changes to their behavior – with one key issue being awareness of the challenges involved.

Research by Ofgem, the UK’s energy regulator, found that awareness was generally ‘low’. In discussions with consumers, “individuals rarely spontaneously linked sustainability to their household energy consumption” and “in general, people were not aware of the impact their current heating systems were having on the environment”.[12] In addition, while people generally felt that the UK’s target of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, was a good idea, they were “apprehensive about what this might mean for their current lifestyles”. Ofgem’s report concluded: “Overall, while most people are supportive of the targets and are aware things need to change in order to prevent further climate change, they are put off by the impact that decarbonizing might have on their own lives in the short term.”

When they were presented with alternative ways to heat their homes, people perceived a range of barriers. They feared the installation process would be inconvenient, or worried that new systems might not be suitable for all properties. The research participants also expressed concerns relating to the aesthetics and reliability of new heating approaches. But the biggest concern identified was “how much any changes would cost [consumers] financially.” Ofgem warned that “many feel they are very unlikely to make changes to their current energy supply or system without support or guidance”.

These findings align with a report published last year by the UK’s Behavioral Insights Team (BIT), which points out that despite nine in ten consumers wanting to make sustainable choices, “many of the necessary behaviors are currently too expensive, too inconvenient, too unappealing or simply not the default or norm we are used to”. In addition to heat pumps being expensive, electric vehicle ownership is too inconvenient for many, the report says. The country’s most popular dishes are meat-based, it adds – and there are no cheap and quick alternatives to long-haul flights.[13]

Taking action to drive change

So, while consumers are broadly supportive of goals to reduce emissions, they tend to hesitate when the necessary action will have a significant impact on our own lives. At the same time, when governments impose regulatory solutions – such as Germany’s heat pumps law – the political pushback can be considerable. Often, significant opposition to emission-reducing measures can cause governments to delay these or water them down, such as the UK government pushing back its ban on the sale of new petrol or diesel-powered vehicles from 2030 to 2035.[14]

Therefore if relying on either voluntary or imposed action tends to be ineffective, is there any other way?

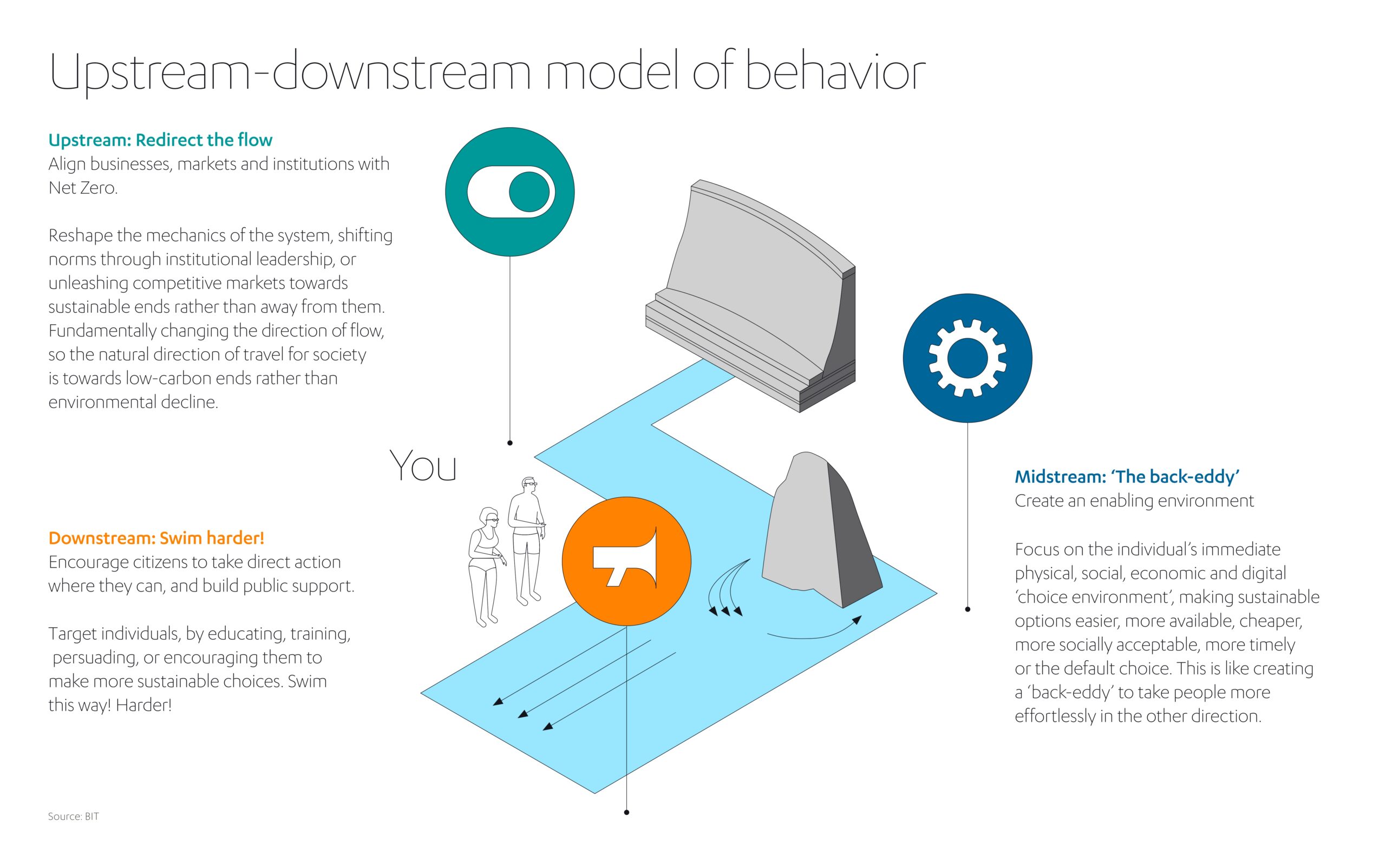

Researchers at the UK’s BIT argue there is. The organization’s 2023 report says that an approach to sustainability that tackles behavior change across multiple levels is likely to work best. The authors point out that while people have the capacity to make individual choices, they do so within “choice environments” that profoundly influence their actions through factors such as pricing, convenience, and norms.

These environments in turn are formed through a range of over-arching elements such as commercial incentives, regulation, and institutional leadership. Based on this model, BIT compares a person facing choices about their behavior to a swimmer in a stream: “free to swim in a different direction but constrained and influenced by the current”.

Rather than focusing on “downstream” interventions that directly target individuals, BIT emphasizes the “midstream” environments that people make choices within, and “upstream” factors which ultimately create those environments. It argues that by targeting people’s environment in this way, “greener behaviors can naturally flourish”.

In relation to energy use in homes, the BIT’s recommendations include reducing electricity prices relative to gas – through measures such as switching environmental levies or price caps. The report also calls on the government to incentivize retrofits among owner-occupiers and landlords – for example, by offering loans to support improvements and linking the level of tax on property purchases to environmental ratings. A national ‘one-stop-shop’ to support green homes is also called for, with the offer including access to a network of approved suppliers, guarantees of fair pricing, and consumer protections. Measures such as these are designed to “build an environment in which green options are naturally the more appealing, easy or default choices”.

Research last year by the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) came to similar conclusions, arguing that consumers are more likely to make green purchases if the government makes interventions focused on “behavioral and human factors”, as well as the systems and contexts that shape these. The IPPO used a model of behavior change which holds that people’s decisions are influenced by numerous factors and contexts, including interpersonal relationships, local communities, businesses and institutions as well as government policy.[15] Its recommendations include creating consistent incentive structures – including green low-interest loans and mortgages for insulation – and new home upgrade agencies that use data-driven segmentation techniques to provide tailored advice and financial support to consumers.

As both of these reports suggest, successful decarbonization efforts can rarely be explained by one factor alone.

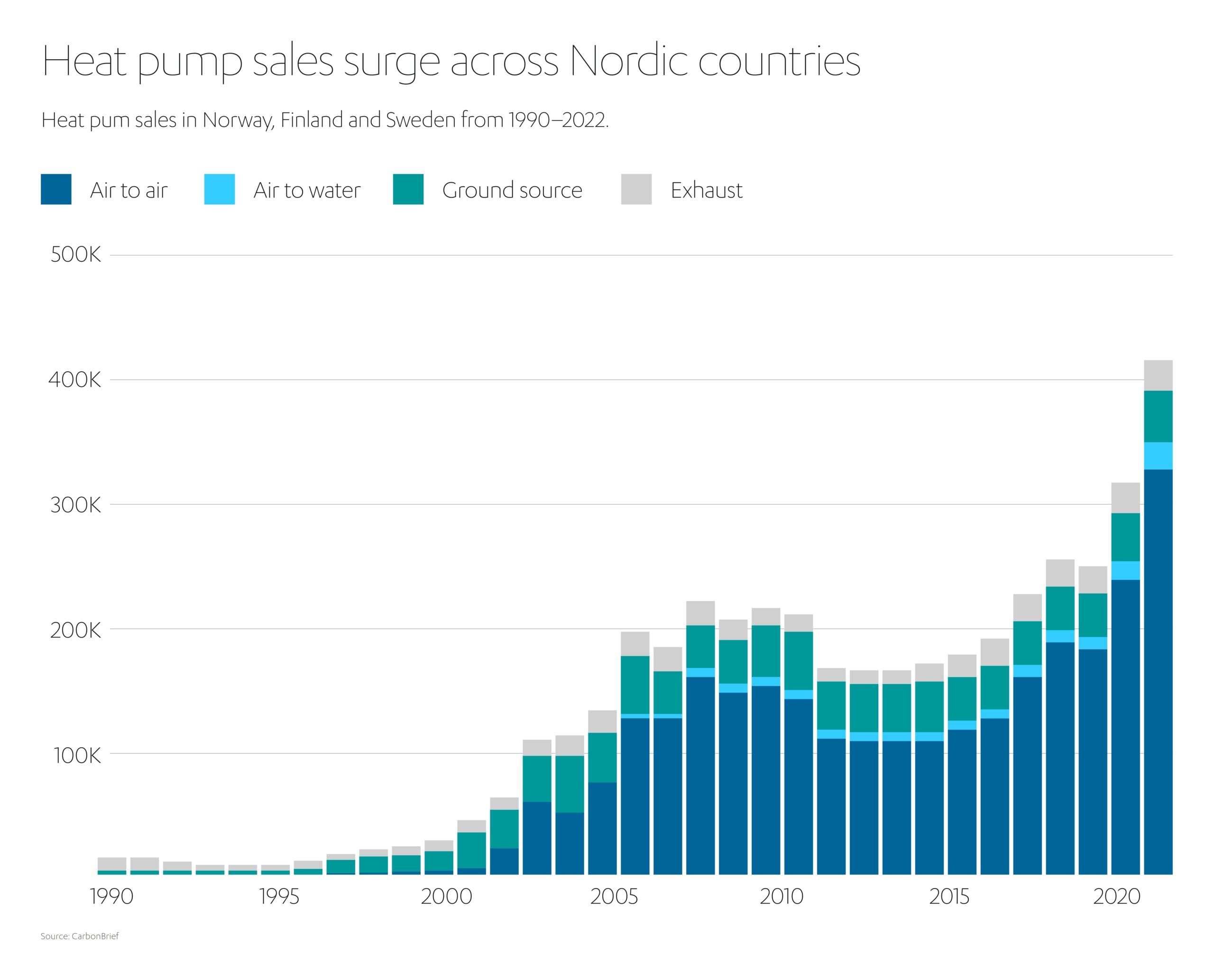

We can see this in Nordic countries such as Finland, Sweden, and Norway – which have the highest installation rates of heat pumps in the world, despite their cold climates. Over the past 30 years, pumps sold have contributed to large drops in CO2 emissions in each of these countries (-72%, -83% and -95% respectively)[16]. They previously used oil extensively for heating but following the oil crisis of the 1970s they all made concerted efforts to move away from fossil fuels.

Dr. Jan Rosenow, director of European programs at the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP) NGO, says that in each country this goal has been a “constant focus in national energy policy”, leading to fossil fuels playing a small role in heating.[17] This provided an important stimulus for research and development of heat pump technology, as well as government interventions such as information campaigns and grant payments. RAP found these countries’ success was down to a mix of policy instruments working in concert, including carbon taxation, government incentives, regulations, quality standards, and consumer protection. Rosenow stresses that there is no single policy that can deliver a mass market for heat pumps. Rather, he recommends a “well-designed policy mix of economic instruments, financial support and regulation, underpinned by coordination and engagement”.

What does the future hold?

These countries’ success with heat pumps shows that transformation is possible. But for the world to meet its decarbonization goals, change on a comparable scale will be needed across a wide range of different areas. Earlier this year, the Politico website highlighted how meeting the European Union’s target of slashing greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2040 would require Europe to “remodel its economy, alter its landscapes, and change its lifestyles”.[18] Assessing what such a scenario would mean in practical terms, it imagined a “continent transformed” – with the process of getting there involving “governing coalitions shattered, companies shuttered,” and farmers besieging Brussels.

The necessary changes would include consumers switching to more plant-based diets, with farmers keeping less livestock and rapidly reducing the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers. As well as more heat pumps, there would be reduced consumption overall and measures to incentivize people to reduce their living space. The majority of cars would be electric, with more use of shared mobility and active travel – and flights would become more expensive thanks to taxes and carbon pricing. The large-scale decarbonization of power would mean more transmission towers and electricity cables, more landscapes dotted with wind turbines and solar panels, and more utilization of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) to provide truly sustainable energy – a field in which Jameel Energy’s Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV) is a rising force.

Active across five continents, FRV develops and manages a growing portfolio of BESS facilities, with a particular focus on the UK, where it has established a BESS Center of Excellence headed by David Menendez.

In 2023, FRV reached financial close on two of its major UK battery storage projects – Contego, West Sussex and Clay Tye, Essex – the latter being one of the largest BESS projects in the UK and the joint largest operational BESS in Europe at the time of its inauguration.

Clay Tye came online at the end of March 2024. It utilizes 52 Tesla Megapack lithium-ion batteries to provide an output of 99 MW and capacity of 198 MWh. Similarly, Contego harnesses an output of 34 MW and capacity of 68 MWh from an array of 28 batteries. FRV has also begun construction of two further UK BESS schemes, this time in the Midlands. Each project covers 1.01 hectares, and together they will generate some 100 MW of energy. The two lithium-ion battery storage systems will allow the import and export of energy connected to the distribution network.

These schemes build on the success of its Holes Bay BESS project in Dorset, UK, active since 2020. The 15 MWh site was the first to go live in the National Grid’s new wider-access Application Programming Interface (API) for the Balancing Mechanism.

FRV now has more than 5 GW of BESS projects at various stages of operation or development in the UK. This is complemented by similar projects in Australia, where the company is developing BESS facilities at Gnarware, in Victoria, and a hybrid solar and BESS plant at Dalby, Queensland – this latter one, a hybrid solar photovoltaic (PV) and BESS facility came on line in July 2024.

It also has a majority stake in a BESS project in Greece, while in February 2024, FRV partnered with AMP Tank Finland Oy for a utility-scale battery energy storage system (BESS) project in Simo, Finland.

Risks of inaction

The risks of failing in the decarbonization challenge were emphasized by Wopke Hoekstra, the European Commissioner for Climate Action earlier this year. When announcing the EU’s climate targets, he stated that “the case for climate action is beyond doubt and requires planning now.” But he added that tackling the crisis “is a marathon, not a sprint. We need to make sure everyone crosses the finish line, and nobody is left behind.”[19]

Hoekstra’s words offer a salutary warning. Climate challenges are different everywhere, but far-reaching changes will be required in many places – including in our homes – if the world is to meet them. Finding the vision and leadership necessary to bring these about is a huge ask for societies and their leaders. Doing so while maintaining just, harmonious communities will be an even greater test.

“The choices we make today to make our homes and our lives more sustainable and less carbon-intensive can make a real contribution to Net Zero goals.

With the right commitment and determination, and with governments who are bold enough to implement the right policies, we can work together to decarbonize our homes, protect the environment and safeguard our societies in future.” says Fady Jameel, Vice Chairman, International, Abdul Latif Jameel.

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019315752?via%3Dihub

[2] https://atlasbuildingshub.com/2023/04/03/fuel-oil-and-propane-space-heating-across-the-united-states/

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019315752?via%3Dihub#bb0075

[4] https://drawdown.org/news/insights/the-powerful-role-of-household-actions-in-solving-climate-change

[5] https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/europe-struggles-heat-homes-without-cooking-planet

[6] https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4713780d-c0ae-4686-8c9b-29e782452695/TheFutureofHeatPumps.pdf

[7] https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/europe-struggles-heat-homes-without-cooking-planet

[8] https://www.politico.eu/article/heat-pumps-exploded-germany-ruling-coalition-green-law/

[9] https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/germany-to-miss-2024-heat-pump-target-by-half/

[10] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618310314

[11] https://theconversation.com/5-charts-show-how-your-household-drives-up-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-119968

[12] https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/sites/default/files/docs/2020/10/consumer_attitudes_towards_decarbonisation_and_net_zero_1.pdf

[13] https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/How-to-build-a-Net-Zero-society_Jan-2023-1.pdf

[14] https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/update-uk-government-announces-delay-zev-mandate

[15] https://theippo.co.uk/home-energy-behaviour-change-barriers-green-purchases-evidence-review/

[16] https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-how-heat-pumps-became-a-nordic-success-story/

[17] https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-how-heat-pumps-became-a-nordic-success-story/

[18] https://www.politico.eu/article/your-life-2040-if-eu-climate-plan-work/

[19] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_588

Added to press kit

Added to press kit