Wind energizes renewables market in record year

It would be a sensible assumption, given the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, to believe that 2020 – and much of 2021 – was a write-off for many sectors of the economy, particularly capital-intensive ones like renewable energy; a period when the world hit pause: societies locked down, projects put on ice, financial growth stalled.

And yet, in some corners of industry, nothing could be further from the truth. Confronted with the stark reality of humanity’s intricate relationship with the natural world, the past 18 months have witnessed a remarkable global doubling-down on the potential of wind power.

New wind energy installations have reached record highs and governments and investors have united to throw their weight behind wind. The industry has proved itself a true force of nature: relentless, indestructible, and capable of whipping up enthusiasm around the world.

The headlines provide succor for anyone passionate about wind, whether from an environmental or an economic perspective.[1]

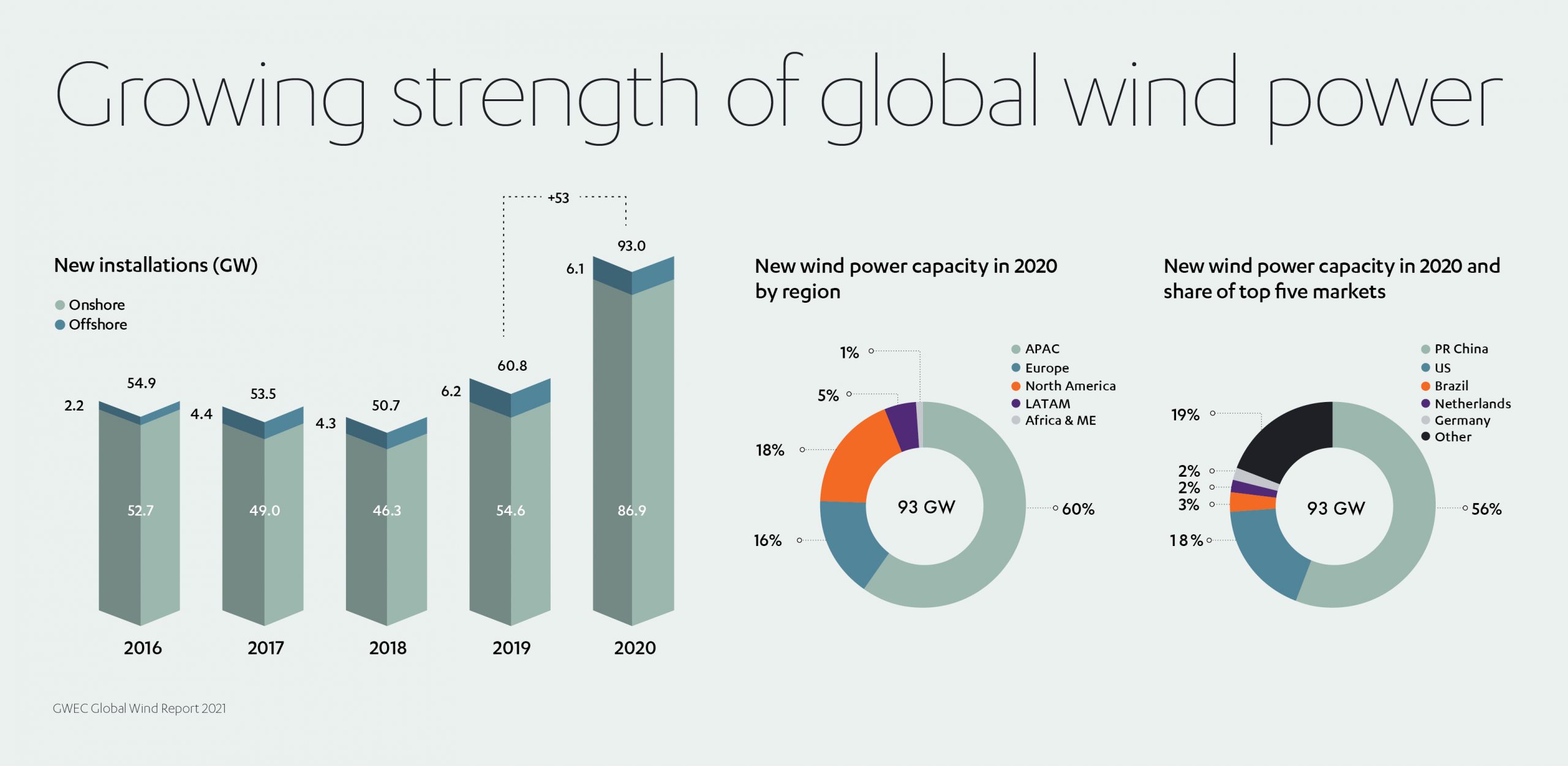

- Globally, the industry installed a record 93 GW of new wind capacity in 2020, bringing total capacity to 743 GW.

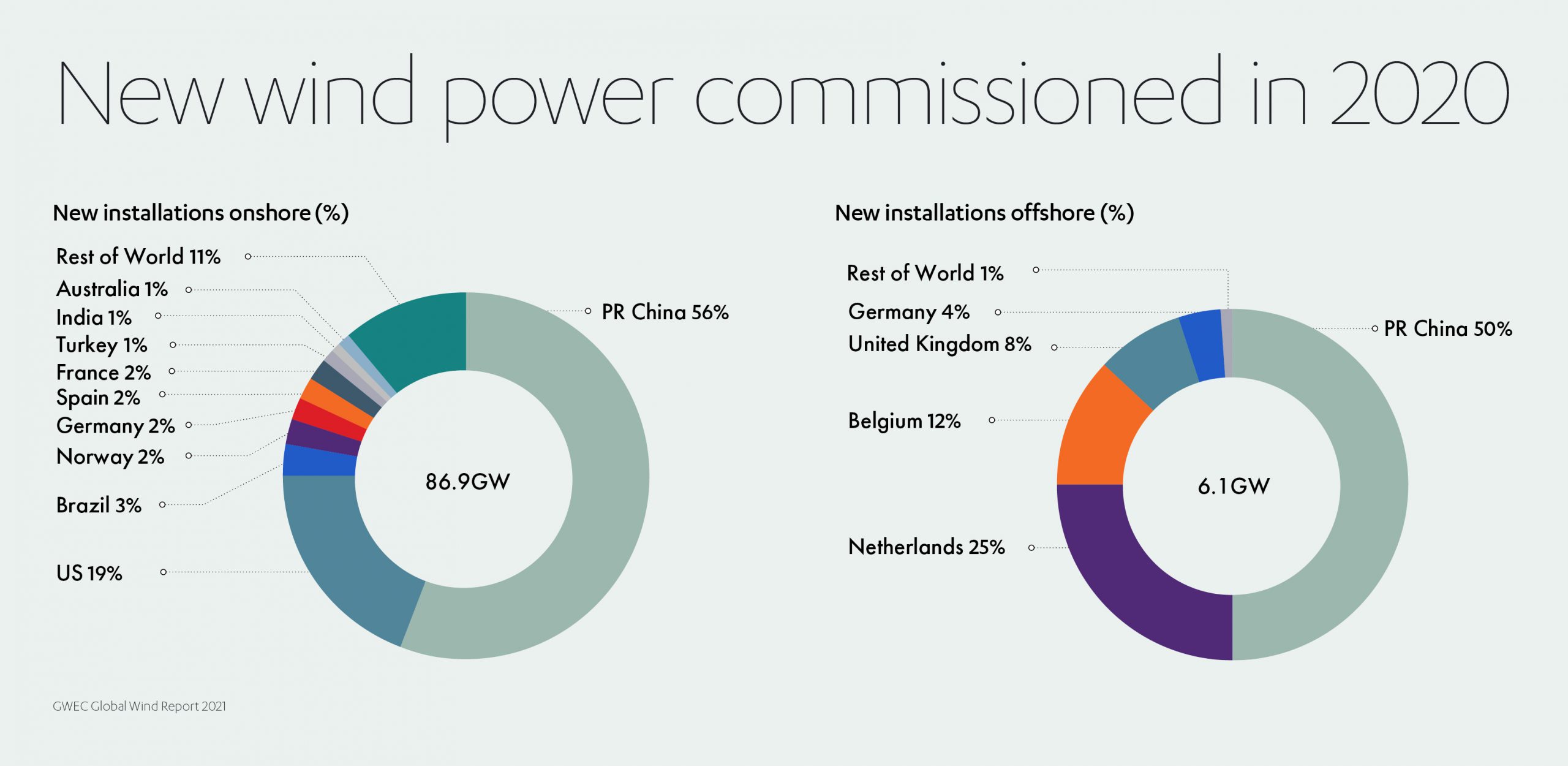

- New onshore installations hit 86.9 GW while the offshore wind market contributed 6.1 GW.

- The world’s top five markets for new installations in 2020 were China, the US, Brazil, Netherlands, and Germany, together comprising 80.6% of the global tally.

- Within the EU, for the first time ever, renewables generated more electricity than fossil fuels thanks to 14.7 GW of new plants joining energy grids.

- Bucking the overall investment slump in power generation, offshore wind financing quadrupled between H1 2019 and H1 2020 to US$ 35 billion.

- The commercial case for wind energy became inarguable, with research showing each dollar invested in wind reaps anywhere from x3 to x7 in returns.[2]

Rest assured – if you’re not yet blown away by wind power, you soon will be.

A breath of fresh air for energy-hungry world

2020’s new 93 GW of wind installations represented a remarkable 53% year-on-year growth.[3]

Highlights from this period of intense activity include China and the US strengthening their status as market leaders, increasing their combined wind power market share by 15% and together accounting for more than three-quarters of all global installations. Asia Pacific, North America and Latin America also experienced record wind growth, reaching 74 GW of new onshore wind capacity, 76% more than 2019. Similarly, Africa and the Middle East registered 8.2 GW of new onshore installations in 2020, maintaining their upward trajectories from the previous year, despite COVID-19 constrictions, while new auctions saw almost 30 GW of new wind power capacity awarded in H2 2020, up from 28 GW in the corresponding period of 2019.

It’s not just on dry land where turbines had investors in a spin. Offshore projects continued to surge, with 6.1 GW of new offshore wind power commissioned last year. It proved to be offshore’s second fastest year for growth ever, with China claiming half of this new activity.

In Europe’s offshore market, the Netherlands led the way, followed by Belgium, the UK, Germany and Portugal. Global offshore capacity hit 35 GW, or almost 5% of the total wind market. Just 1 GW of offshore wind capacity was awarded through auctions globally in 2020, but more than 7 GW of new tenders were announced – an indication of more rapid growth around the corner.

If there is a line-in-the-sand moment for the environmental crisis, 2021 could be that line. The UK hosted the COP26 UN Climate Change conference at the end of October.

If there is a line-in-the-sand moment for the environmental crisis, 2021 could be that line. The UK hosted the COP26 UN Climate Change conference at the end of October.

Billed as the final chance for a coordinated global effort to counteract global warming, COP26 saw leaders from around the world outline new commitments to quit fossil fuel dependency and achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

With the stakes so high, some doubt that such a goal can be met.

Present plans to cut global carbon emissions, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), will fall 60% short of targets necessary for net zero.[4] The IEA estimates an extra US$ 4 trillion of investment will be needed to make net zero achievable.

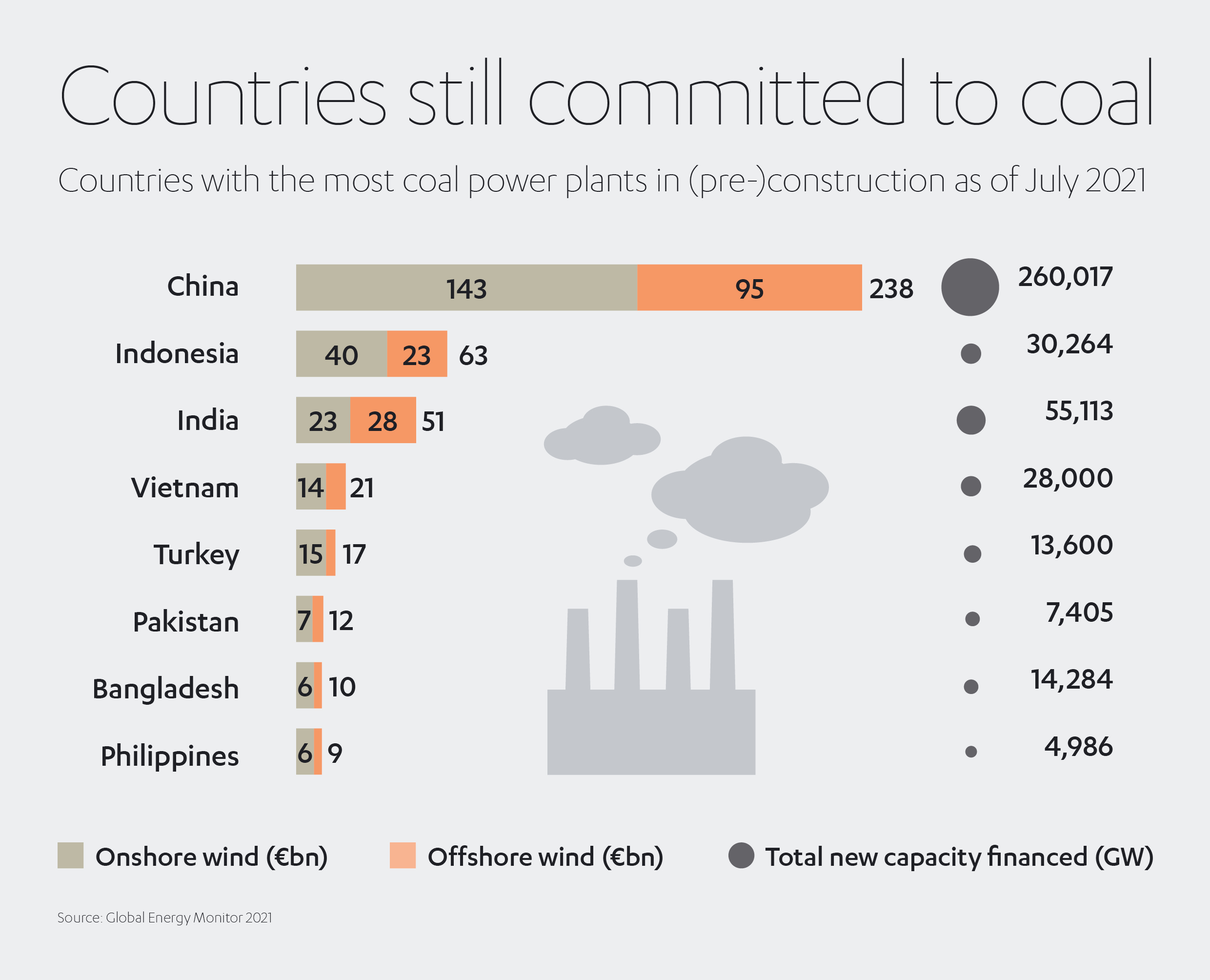

Fatih Birol, IEA executive director, has cautioned that governments’ pandemic recovery schemes are still placing too much emphasis on coal.[5] Among G20 countries, for every US$ 1 per head earmarked for clean energy in Covid recovery packages, US$ 1.05 per head is being spent supporting fossil fuel industries.[6]

Simultaneously, dual challenges lurk on the horizon.

Although China has pledged to end investments in coal power stations abroad, it currently remains committed to building new coal power plants domestically.[7]

Meanwhile, the case for wind is weathering legislative setbacks in both East and West, with the expiration of the Feed-in Tariff in China and the phase-out of the Production Tax Credit in the US.

With global energy consumption tipped to double by 2050, it seems time is running out to step back from the brink of environmental calamity.[8]

Industry braced for game-changing five years

Despite these challenges, the market outlook for wind remains extremely buoyant. Indeed, Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) chief Ben Backwell says society could remember 2021 as “the year when the world finally turned the corner in confronting the climate crisis by adopting a decisive path of collective action”.[9]

Why the optimism?

GWEC is predicting more than 469 GW of new wind capacity coming online in the next five years, or approximately 94 GW per year between 2021 and 2025. This includes an average of 79.8 GW new onshore wind capacity each year (total: 399 GW). The rate of new offshore installations is expected to quadruple during the same period (total: 70 GW), boosting offshore’s market share from 6.5% today to 21% by 2025.

Impressive – though still falling short of the 180 GW new installations thought to be needed annually to ensure IPCC global heating goals are met.

Still, when it comes to the existential peril of climate change, we increasingly find that necessity breeds action.

The EU, for instance, aims to greenlight 30 GW of new turbines per year between 2021 and 2030 – part of its Fit-For-55 package[10] aimed at reducing emissions across the continent by 55% by that date.[11]

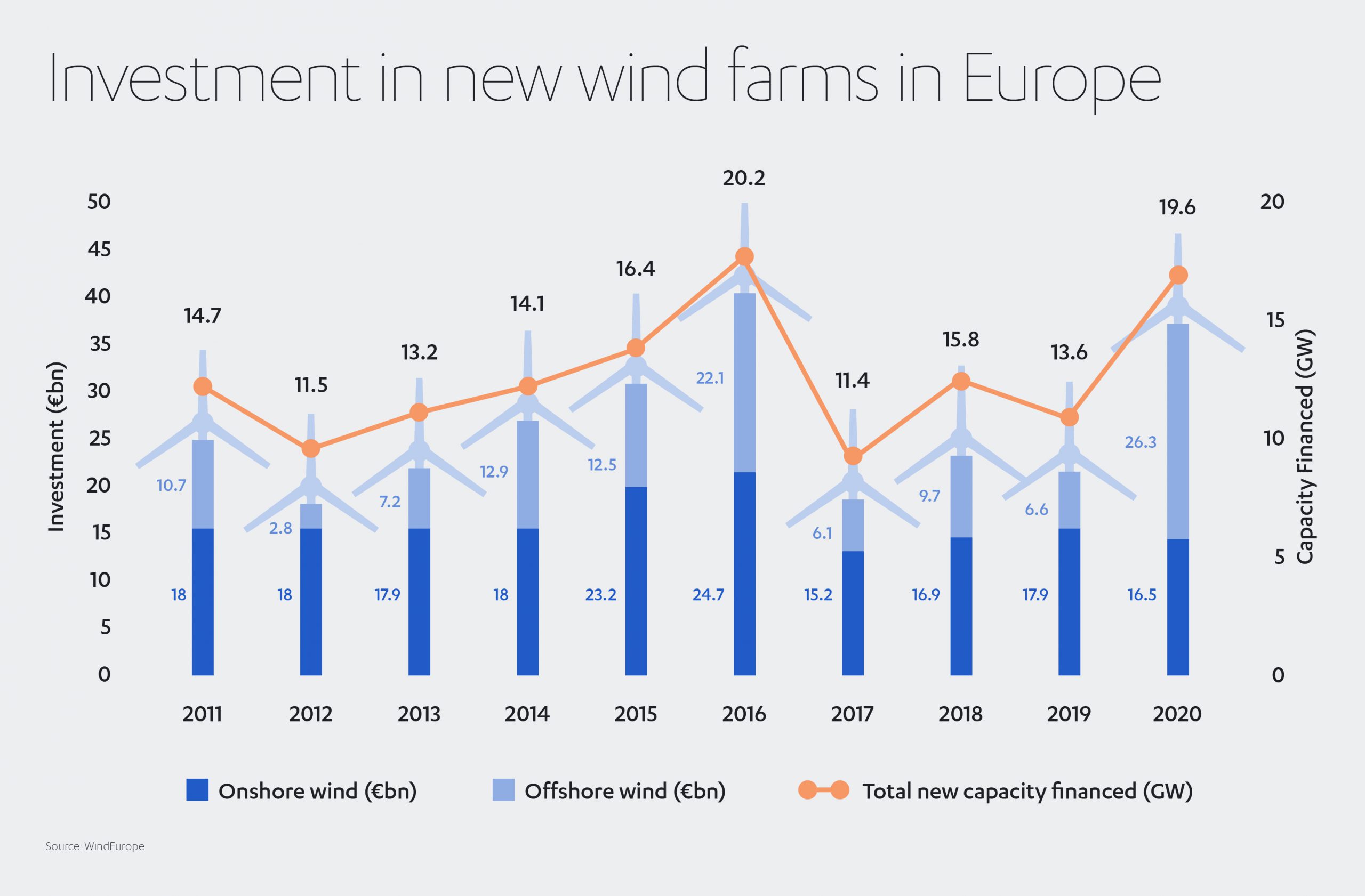

Certainly, Europe is moving in the right direction, confirming €43 billion of new wind farm investments in 2020, comprising €17 billion for onshore wind (13 GW) and €26 billion for offshore wind (7 GW). This marks a 70% investment leap from the previous year and includes funding for two major offshore developments currently under construction: Hollandse Kust Zuid in the Netherlands and Dogger Bank in the UK.

Leading the charge, the UK accounted for €13 billion of the €43 billion total, followed by the Netherlands with €8 billion, France with €6.5 billion and Germany with €4.3 billion.[12]

Plans for the wider rollout of wind continue to gather pace. The UK government has set aside a US$ 220 million kitty to invest in offshore wind port facilities around British waters – part of an initiative to generate 1 GW of energy from floating arrays by 2030.[13] The UK is also throwing its resources behind a US$ 4.1 billion Clean Green Initiative, a scheme aimed at helping developing nations establish renewable energy infrastructure and pursue ‘green growth’ post-pandemic.[14] Fossil fuel companies are waking up to the wonder of wind too. Norwegian oil giant Equinor has unveiled a first glimpse at its new floating wind platform design – a semisubmersible turbine foundation with steel beams connecting three floatation columns.[15] The system has several advantages over standard offshore turbine designs, being less prone to breakdown and quicker to assemble. The new-look turbines will allow the deployment of GW-size floating projects in a single phase and will feature in Equinor’s bid for the 15-acre ScotWind offshore lease offering.

Betting on the future appears to make sound business sense. A new report from the European Technology and Innovation Platform on Wind (ETIPWind) declares electrification to be the cheapest way of decarbonizing Europe’s economy. Its research suggests some 75% of Europe’s energy needs will be met by electrification by 2050, with wind supplying two-thirds of that total.[16]

Each new turbine generates an estimated €10 million of economic activity in Europe; with the right support and incentives, it is thought that the industry could create 150,000 new jobs by 2030.[17]

Technology rewriting the rule book

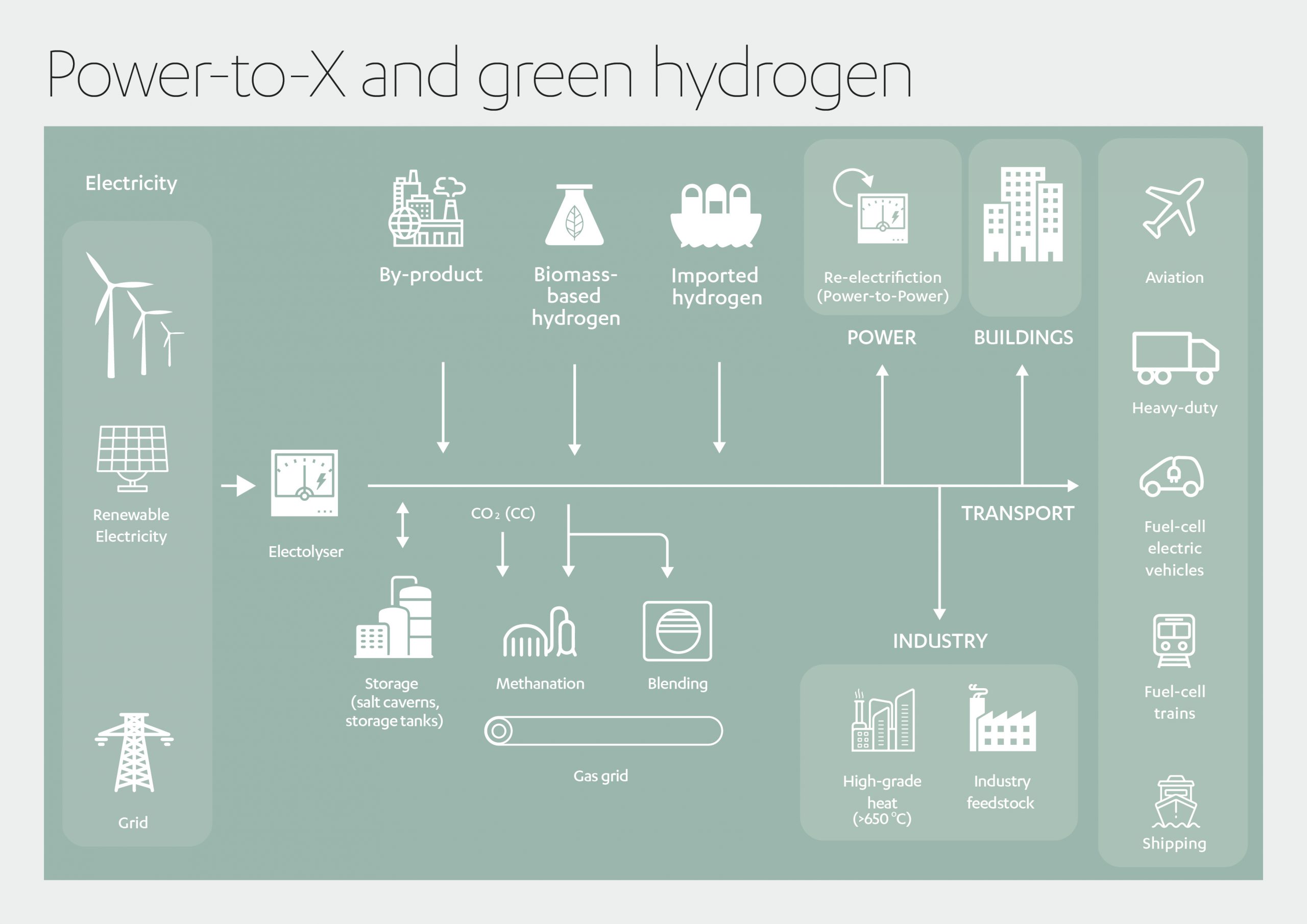

A common argument against renewable energy is the issue of fluctuating supply: what to do, for instance, when the wind fails to blow with vigor, yet our factories and transport systems still need to operate? Encouragingly, progress continued during 2020 and into 2021 on concepts involving battery storage and so-called ‘Power-to-X’ technology.

Power-to-X involves surplus energy being diverted from the grid during periods of over-supply and transformed by electrolysis into hydrogen for eventual use in different sectors: power-to-chemicals, for example, or power-to-fuel, or power-to-gas. The last 12 months has seen further progress in reconversion technologies such as gas turbines, combined cycle power plants, reciprocating engines and fuel cells.

Such breakthroughs provide a powerful boost to projects like the vast offshore NortH2 wind farm (a joint venture between Equinor, Gasunie, Groningen Seaports, RWE and Shell Nederland) located off the coast of the Netherlands. NortH2 aims to generate 4 GW of green hydrogen by 2030, rising a decade later to 10 GW.[18]

Elsewhere, commissioning is expected by the end of 2021 on a 200 MW onshore wind farm in Hebei Province, China, using electrolysis to produce 10 MW of green hydrogen annually.

Further south, Western Australia’s enormous 15 GW wind/solar Asian Renewable Energy Hub is expected to become operational in 2027, scaling up to 26 GW of renewable power with green hydrogen and ammonia production.

Battery storage technology, too, is continuing to decline in price, with battery prices falling by up to 90% over the last decade.

At Abdul Latif Jameel, we know that making big changes requires bold gestures, which is why we fund research into cutting-edge battery technology via our flagship renewables business Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV), part of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy.

FRV-X, the innovation arm of FRV, is involved in two groundbreaking energy storage projects in the UK, in partnership with British renewable energy developer Harmony Energy: the 34 MW Contego site, using a series of 28 Tesla Megapack batteries for capacity of 68 MWh; and the 7.5 MW Holes Bay development, providing the capability to store energy from renewable sources and afford peak-time flexibility to the UK National Grid. In addition, the partners recently announced plans for the UK’s biggest Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) at Clay Tye in Essex.

Felipe Hernández, Managing Director FRV-X, said: “These projects underline our commitment to renewable energy in the UK and our continuous support towards its transition to a decarbonized energy system. In the near future, we aim to keep growing our energy storage pipeline, not only in the UK, but also in all other markets where we have a presence”.

FRV is also behind the 5MW Dalby 1 hybrid solar and Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) project in the Dalby region of Queensland, Australia, due for completion in December this year.

These activities supplement FRV’s other green energy generation projects, including the Hybrid Wind Rarinco and Solar Punta del Viento 343 MW hybrid 945 MWh/year project in Chile, set to supply some 391,841 households when it becomes operational in 2023, and recently received environmental licensing approval.

Some of the most exciting advances in wind power could happen on Abdul Latif Jameel’s doorstep in Saudi Arabia, highlighted this year by GWEC as a ‘market to watch’.[19]

GWEC ranks Saudi Arabia 13th globally in terms of onshore wind production potential. Annual onshore wind speeds at designated sites register between 6-8 m/s and remain consistent during most of the year. If exploited fully, it is thought that Saudi Arabian renewables could create up to 750,000 jobs by the end of the decade.

The country’s National Renewable Energy Program (NREP) is targeting 58.7GW of renewables by 2030, with wind comprising 16 GW. Saudi Arabia’s first wind auction resulted in the US$ 500 million Dumat-al-Jandal project; a 400 MW wind farm due to commence operations in the first quarter of 2022.

The country’s National Renewable Energy Program (NREP) is targeting 58.7GW of renewables by 2030, with wind comprising 16 GW. Saudi Arabia’s first wind auction resulted in the US$ 500 million Dumat-al-Jandal project; a 400 MW wind farm due to commence operations in the first quarter of 2022.

Elsewhere in Saudi Arabia the case for wind is further validated by Neom, a renewables-only smart city in Tabuk Province, currently under construction. With phase one set for completion in 2025, Neom will stake a claim as the world’s largest green hydrogen project, powered by 4 GW of wind and solar energy.

As we can see, where there’s a wind, there’s a way.

Wind promises a new direction

Deputy President & Vice Chairman,

Abdul Latif Jameel

It might be tempting to believe that by reducing global power consumption, COVID-19 slammed the brakes on climate change. But this is only a temporary respite. As Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel, discusses in his recent Spotlight article, climate change is not on pause while the world grapples with COVID-19. While carbon emissions indeed dropped 6% in 2020, they are expected to rise by 4% across G20 nations in 2021 as industry ramps up once more.[20] Several countries, among them India and China, are actually set to surpass their 2019 emission levels.

“The figures may vary from year to year, but the underlying truth remains stark,” says Fady. “Wherever we live in the world, whatever our relative wealth, global warming remains a threat to our way of life.

“At Abdul Latif Jameel, we are passionate about leading by example, showing how private investment can spur the public sector to tangibly improve people’s lives and prospects, now and into the future.

“No one asked for a planet hovering on the cusp of 2 degrees warming, just as no one predicted a pandemic to run rife across the world. But what we cannot change we must not lament – there is simply too much work to do.”

Looking ahead, GWEC outlines several key steps, from the practical to the psychological, for placing wind power squarely at the heart of the green energy transition:[21]

- Honesty: legislators and regulators need to create a sense of urgency by emphasizing the gulf between where we are now and where we need to be.

- Urgency: planners must take a ‘climate emergency’ approach by cutting red tape and streamlining the permission process for new wind farms.

- Fairness: governments should help drain the energy system of fossil fuels and ensure the social debts of carbon emissions are fairly settled.

- Coordination: stakeholders in the renewables market must unite to help tough-to-transition industries such as chemicals, agriculture, and transport to decarbonize.

“The weather can be friend or foe – the choice is ours,” adds Fady Jameel. “By working in unison and harnessing the power of nature, we can together propel wind power up the energy agenda and help protect our planet.”

[1] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[2] https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Sep/IRENA_Transforming_2019_Summary.pdf

[3] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[4] https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/13/carbon-emissions-will-drop-just-40-by-2050-with-countries-current-pledges

[6] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/12/china-coal-fired-plants-uk-cop26-climate-summit-global-phase-out

[8] https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Oil%20and%20Gas/Our%20Insights/Global%20Energy%20Perspective%202019/McKinsey-Energy-Insights-Global-Energy-Perspective-2019_Reference-Case-Summary.ashx

[9] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[10] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/

[11] https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/its-official-the-eu-commission-wants-30-gw-of-new-wind-a-year-up-to-2030/

[12] https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/money-pouring-into-wind-energy-despite-covid-but-are-there-enough-projects-out-there/

[13] https://www.rechargenews.com/wind/britain-bets-on-floating-wind-with-220m-kickstart-pot-for-coastal-industrial-hubs/2-1-1091349

[14] https://www.rechargenews.com/energy-transition/britain-launches-developing-nations-angled-green-funding-package-plan/2-1-1091929

[15] https://www.rechargenews.com/wind/equinor-eyes-gigawatt-scale-floating-wind-off-scotland-with-new-foundation-concept/2-1-1091513

[16] https://etipwind.eu/files/reports/Flagship/fit-for-55/ETIPWind-Flagship-report-Fit-for-55-set-for-2050.pdf

[17] https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/money-pouring-into-wind-energy-despite-covid-but-are-there-enough-projects-out-there/

[18] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[19] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

[20] https://www.climate-transparency.org/g20-climate-performance/g20report2021

[21] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GWEC-Global-Wind-Report-2021.pdf

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit