The economic costs of climate change

More soaring temperatures, higher tides and higher winds. More rain, more storms, more pests, more disease pathogens and more fires. Less rain, less glacial ice and less habitable landmass. 2019, and the years immediately preceding it, have seen a string of climate-change-related disasters around the world, from floods to wildfires, hurricanes to drought.

By Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel

Warmer, wetter, wilder

In March, Cyclone Idai made landfall in Mozambique, killing more than 1,000 people and causing flooding and power outages throughout southern Africa. In August, huge wildfires swept across several of the Canary Islands, while monsoon-related floods killed more than 200 people across India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Chile has been suffering the worst drought in some 60 years.

More recently, high tides and a storm surge, the like of which have not been seen in Venice for half a century, submerged much of the city beneath 187cm of water. In California and Australia, wildfires destroyed thousands of acres and left whole communities homeless.

UK-based humanitarian charity Oxfam estimates that ‘extremes in weather’ mean that more than 52 million people across 18 countries in Africa are facing hunger[1]. Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the huge fires that swept through the Amazon earlier this year, NASA identified that many of the fiercest conflagrations were in “water-stressed areas”[2] where human activity has reduced the amount of water vapor released by plants, making them more susceptible to fire[3].

The seemingly increasing frequency of these incidents comes amid growing recognition that previous projections of the scale and pace of climate change may have been woefully underestimated. In fact, as far back as 2013, a report in the journal Global Environmental Change found that “at least some of the key attributes of global warming from increased atmospheric greenhouse gases have been under-predicted, particularly in IPCC assessments of the physical science.” [4]

This historic failure to accurately predict the accelerating pace of climate change brings with it a very real risk that we are also underestimating the reality of its economic costs. After all, estimates based on flawed data will inevitably be inaccurate themselves.

Compounding this, is our human tendency to base estimates of future cost on our previous experiences. For instance, basing the financial impact of an impending hurricane purely on our past experience of hurricanes. Statisticians call this ‘stationarity’: using past occurrences to define future predictions. Many economists have been slow to appreciate – or at least consider – the link between stationarity and predictions about the true costs of climate change.

Climate damage was regarded as a specific challenge to be ‘fixed’ on our path to continuing economic growth, because that is what has always happened in the past. But when conditions change so rapidly and so acutely that the past is no longer a reliable guide – as with climate change – estimates of cost based on the past quickly become irrelevant.

Added to this is the cascade effect of climate change. One reason the impacts of climate change are hard to fathom is that they will not occur in isolation, but will likely feed into each other, altering, exacerbating, mitigating or slowing outcomes in as-yet unknown ways.

For example, a warming climate could reduce food production in a country, leading to widespread malnutrition that diminishes the capacity of its population to withstand heat and disease, leading to an increase in mortality and making it harder for them to adapt to climate change. In a worst-case scenario, climate change leads to economic recession, which leads to social and political disruption that undermines countries’ capacity to prevent further climate damage.

Not an easy chain of events to simply put a cost on, and one reason why, through the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS) at MIT, Community Jameel is helping to fund pioneering research that could help make food and water systems around the world more resilient and sustainable in the face of climate change.

These sorts of cascading effects have only recently begun to be captured in economic models of climate change – but a shift in attitudes appears to be underway.

Is climate policy beginning to catch up with climate science?

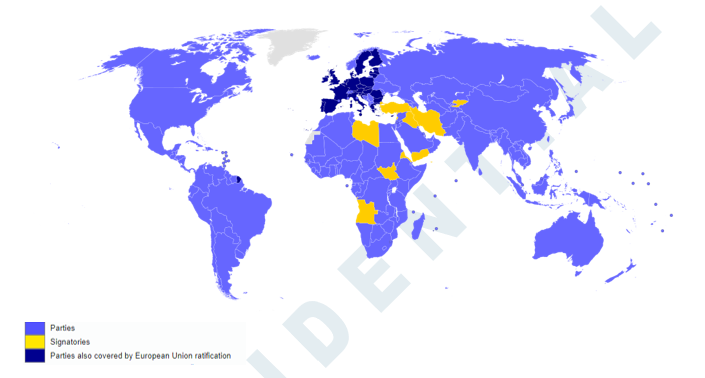

One year after the Paris Agreement in 2016, the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Action Summit in New York saw an announcement that some 77 countries had committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Several, including the UK, France, Sweden and Norway, introduced legislation to that effect. Unfortunately, for many others – some critical to achieving global targets – such a goal remains merely ‘aspirational’.

As the impacts of climate change begin to escalate, the monetary costs will be felt at every level of the economic system: from individual businesses, through to national balance sheets, even impacting the entire global financial structure.

Businesses braced for blow to bottom line

In June 2019, research by charity CDP – formerly known as the Carbon Disclosure Project – revealed that 200 of the biggest listed companies in the world had forecast that climate change could cost them a combined total of almost US$ 1 trillion, with much of the pain due to come in the next five years. [5]

The CDP’s Climate Change Report 2018 says that companies, from Apple and Microsoft to Unilever and China Mobile, anticipated a total of US$ 970 billion in extra costs.

The CDP’s Climate Change Report 2018 says that companies, from Apple and Microsoft to Unilever and China Mobile, anticipated a total of US$ 970 billion in extra costs.

Likely triggers included costs associated with higher temperatures, chaotic weather patterns and the pricing of greenhouse gas emissions. Approximately half of these costs are regarded as “likely to virtually certain.”

According to a UN International Labor Organization (ILO) report published in July 2019[6], given a 1.5°C temperature rise by the end of the century, we can expect to see an increase in work-related heat stress and loss of productivity equivalent to 2.2% of total global working hours (or 80 million jobs) by 2030. Agriculture and construction will be two of the sectors worst affected. Some 940 million people work in agriculture worldwide, and the sector could account for 60% of global working hours lost due to heat stress by the year 2030. Global working hours in construction could be reduced by 19% by the same date.

Productivity isn’t the only pillar of the economic model under stress – so too is purchasing. The impact of extreme natural disasters equates to a global US$ 520 billion loss in annual consumption. [7]

A 2012 study led by Melissa Dell, Harvard professor of economics and faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research, indicates that every 1°C increase in average temperature translates on average to a fall in per capita income of 8%. [8]

Natural disasters alone force some 26 million people into poverty each year – and without urgent action, climate change could push an additional 100 million people into poverty by 2030. Such economic stagnation could have a paralyzing effect on bottom lines, for businesses and countries alike.

‘First world’ economies vulnerable to GDP shrinkage

Effectively, business losses from climate change will reinforce already existing economic disparity, as those in the poorest regions of the world, with fewer resources to adapt as quickly or effectively, will inevitably suffer the most significant loss.

The World Bank believes that as many as 143 million people across three developing regions could become climate migrants by 2050[9], with individuals, families and even whole communities forced to seek places to live that are less susceptible to climate change.

“Bear in mind that we, the developing states, are the least responsible for the causes of climate change, but we are the very first victims of it,” said Simon Stiell, Minister of Climate Resilience in Grenada, one of the convening nations behind the Global Commission on Adaptation (GCA).

“Bear in mind that we, the developing states, are the least responsible for the causes of climate change, but we are the very first victims of it,” said Simon Stiell, Minister of Climate Resilience in Grenada, one of the convening nations behind the Global Commission on Adaptation (GCA).

The GCA is led by former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and International Monetary Fund Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, and comprises countries such as China, Mexico and the UK, as well as climate-vulnerable countries such as Bangladesh and the Marshall Islands.

It was formed in 2018 to help ensure that social and economic systems can withstand the consequences of climate change.

This doesn’t mean, though, that developed markets can afford to be complacent, safe in the knowledge their economies are protected from the worst effects of climate change. If anything, the impact could be greater, as relatively speaking, they have more to lose.

An August 2019 study from the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) estimates far higher potential costs from climate change than previously thought, particularly within the industrial world. [10]

An August 2019 study from the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) estimates far higher potential costs from climate change than previously thought, particularly within the industrial world. [10]

For example, a continued temperature increase of about 0.04°C under a ‘business as usual’ scenario (where carbon continues to be emitted at its current rate) would mean a 7.2% cut to GDP per capita worldwide by 2100.

The NBER estimates that the US could lose up to 10.5% of its GDP by 2100, equivalent to over US$ 2 trillion at 2018 levels. Canada’s GDP would reduce by more than 13% (approx. US$ 221 billion), while Japan, India and New Zealand could each lose around 10% (around US$ 500 billion, US$ 270 billion and US$ 20 billion respectively).

The UK government’s landmark Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change[11] warns the costs of extreme weather events alone (storms, hurricanes, typhoons, floods, droughts, heat waves) could reach 0.5 – 1% of global GDP annually by the middle of the century – or higher still if the world continues to warm.

It raises the specter of annual flood losses in the UK growing from 0.1% of GDP today to 0.2 – 0.4% if global temperatures rise by 3 or 4°C. Furthermore, it suggests that heat waves such as the one experienced in Europe in 2003, causing agricultural losses of some US$ 15 billion, will be ‘commonplace’ by mid-century.

Financial onus of climate change spans borders

Few economies will emerge unscathed from the burden of tackling climate change. It is, after all, a uniquely global crisis which recognizes no borders, whether cultural or economic.

The Stern Report says nothing less than a ‘transformation’ in the flow of international carbon finance will be necessary to achieve meaningful emissions reductions. This strategy comes at a price. Incremental costs of low-carbon investments in developing countries are likely to be ‘at least’ US$ 20-30 billion annually. Sharing these costs equitably will hinge on a major expansion of trading schemes, such as the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS).

Furthermore, research suggests that the ‘opportunity cost’ (i.e. financial potential left unexploited) of forest preservation within the eight countries accounting for almost three-quarters of emissions from land use could run to US$ 5 billion annually. How these sacrifices can be fairly compensated is part of an ongoing debate.

Whichever direction one looks, the costs of climate change escalate. Within OECD countries alone, additional costs for bolstering new infrastructure and buildings against climate change could reach US$ 150 billion per year (0.5% of GDP)[12].

Take the recent announcement by the Drax Group of its plan to make the Drax power plant in North Yorkshire, UK, carbon negative within 10 years – becoming the world’s first carbon-negative business in the process.[13] Even in its current form, having already converted its huge coal generation units to run on renewable biomass, Drax requires government subsidies of £2 million (US$ 2.63 million) a day to operate. Its new initiative, to capture millions of tons of carbon emitted by the plant and store it underground, will require yet further state support to become viable.

It is clear that a global crisis requires a global response – and part of that means ‘selling’ the notion that climate-focused investment can reap measurable benefits.

A new kind of cost/benefit analysis

Research from the GCA[14] points to potential benefits of tackling climate change that could potentially far outweigh initial costs.

According to the research, the world must invest no less than US$ 1.8 trillion by 2030 to prepare for the effects of global warming – but the benefits that come from this investment could be worth up to four times as much.

According to the research, the world must invest no less than US$ 1.8 trillion by 2030 to prepare for the effects of global warming – but the benefits that come from this investment could be worth up to four times as much.

It estimates that a US$ 1.8 trillion investment in weather warning systems, infrastructure, dry-land farming, mangrove protection and water management by 2030 would yield US$ 7.1 trillion in benefits.

It points to the Thames Barrier in the UK, which protects 1.3 million Londoners from flood waters, as an example of the benefits that can accrue from this kind of foresight.

Although construction costs for the barrier ran to £534 million (US$ 686 million), without it, flood risk would have precluded the investments that allowed Canary Wharf to become one of the most important financial centers on the planet, home to many of the world’s largest financial businesses and generating huge tax revenues for the UK government.

Although construction costs for the barrier ran to £534 million (US$ 686 million), without it, flood risk would have precluded the investments that allowed Canary Wharf to become one of the most important financial centers on the planet, home to many of the world’s largest financial businesses and generating huge tax revenues for the UK government.

Similarly, looking to the future, the GCA suggests that investing US$ 800 million on warning systems for storms in developing countries could avoid the need to spend up to US$ 16 billion per year mitigating the damage done by such storms.

Natural disasters currently cost about US$ 18 billion a year in low and middle-income countries just as a result of damage to power and transport infrastructure, triggering wider disruption for households and firms to the tune of US$ 390 billion a year[15].

“Governments and businesses need to radically rethink how they make decisions,” Ban Ki-moon said, at the report’s launch. “We need a revolution in understanding, planning and financing that makes climate risk visible.”

Further research shows that countries could collectively save around US$ 250 billion a year by reforming inefficient energy systems and removing costly energy subsidies. Such numbers are a powerful motivator. [16]

Apart from money saved, there is also money to be made. The UK’s Stern Report envisions huge new business opportunities as demand for low-carbon, high-efficiency goods and services grows: “Markets for low-carbon energy products are likely to be worth at least US$ 500bn per year by 2050, and perhaps much more,” it states, before recommending that companies and countries alike position themselves to capitalize on these opportunities.

Specific areas where prompt investment could trigger rapid returns include improved energy efficiency and reduced gas flaring, as well as “large-scale pilot programs [that] would generate important experience to guide future negotiations”.

Delayed response increases risk, jeopardizes opportunities

Given the high stakes, governments globally should invest immediately in measures to combat climate change, protect our economies and safeguard our communities – thus avoiding even greater outlays in the future to try and rebuild them.

There are some elements of this puzzle that can be costed – for example, the decarbonization of the world’s electrical power generation and distribution systems. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that circa US$ 26 trillion of investment in low-carbon generation is needed by 2050. Decarbonization of society at this scale demands comprehensive change in just about every part of our current economic model. The power and utilities sector must play a pivotal role in the majority, or perhaps even all, of these shifts.

Change is never easy. As in any transition, what is for some a seemingly insurmountable cost is for those willing to embrace a new world, an investment opportunity and future revenue stream. A future low-carbon economy – just like the transformation in the industrial revolution or to a digitized world – presents vast developmental opportunities in areas including electrified transportation solutions, sustainable heating and cooling, the rise of a ‘hydrogenized’ economy and smart, loading-balanced, electricity grids to optimize supply and demand fluctuations.

I hope that public-private partnership will be part of the answer and that institutional investors seeking predictable returns will join with governments to help secure the necessary capital. We can then marry this with those pioneering the building of our clean energy systems of tomorrow.

[1] More than 52 million across Africa going hungry due to weather conditions, Oxfam, November 7, 2019

[2] https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-satellites-reveal-major-shifts-in-global-freshwater

[3] A recent systematic increase in vapor pressure deficit over tropical South America, Nature, October 25, 2019

[4] Climate change prediction: Erring on the side of least drama?, Global Environment Change, Vol 23, Issue 1, February 2013

[5] Major risk or rosy opportunity: Are companies ready for climate change?, CDP, 2018

[6] Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on productivity and decent work, International Labour Organization, 2019

[7] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/overview

[8] https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/dell/files/aej_temperature.pdf

[10] https://www.nber.org/papers/w26167

[11] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/4/3/executive_summary.pdf

[12] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/4/3/executive_summary.pdf

[13] “Drax owner plans to be world’s first carbon-negative business”, The Guardian, 10 December 2019.

[14] Adapt now: A global call for leadership on climate resilience, GCA, 2019

[15] Lifelines: The resilient infrastructure opportunity, World Bank, 2019

[16] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/4/3/executive_summary.pdf

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit