Turning the tide

Leonardo DaVinci described water as “the driving force of all nature”. But, today, our marine life ecosystem hangs in the balance and is under constant and increasing threat. What is causing so many problems? Why is it so urgent and what actions can we take to rectify the situation?

By Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel

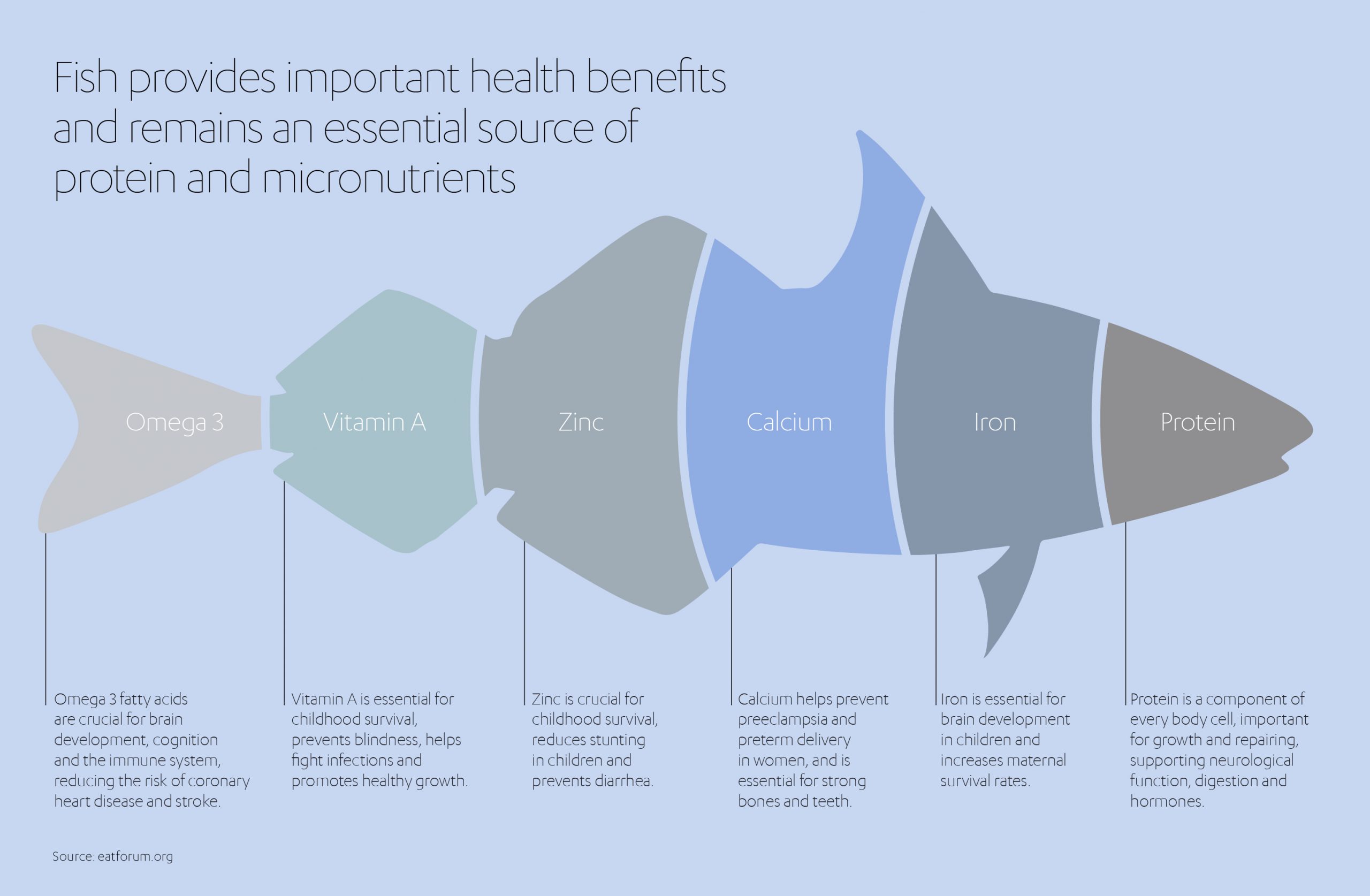

Our oceans comprise 70% of the planet – covering a staggering 362 million square kilometers – and supply more than half of the World’s oxygen[1], [2]. From our earliest recorded history, oceans have enabled trade between countries from East to West, led explorers to discover new continents, and been a primary source of food sustenance. Until today, the sea remains the economic mainstay of many coastal communities and its marine life continues to provide essential nutrients for a healthy diet, particularly in less-developed countries[3].

Yet, our oceans and marine life are under threat. Water temperatures have increased by around 0.1 degree Celsius over the past century[4]. At a first glance, this figure may not seem significant, but it is already having a major effect on the diversity of the ocean’s marine life. Coral reefs, which provide a home and protection for thousands of aquatic species[5], are also under threat, as rising sea temperatures kill the algae that keep the reefs alive[6].

The issue extends further to the biodiversity of our freshwater aquatic systems. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), our rivers, lakes and freshwater wetlands contain 10% of all marine species with a greater diversity per square kilometer than our oceans or on land[7]. But human interventions such as pollution, man-made dams, overfishing and sand mining are undermining both their diversity and abundance.

Swelling seas

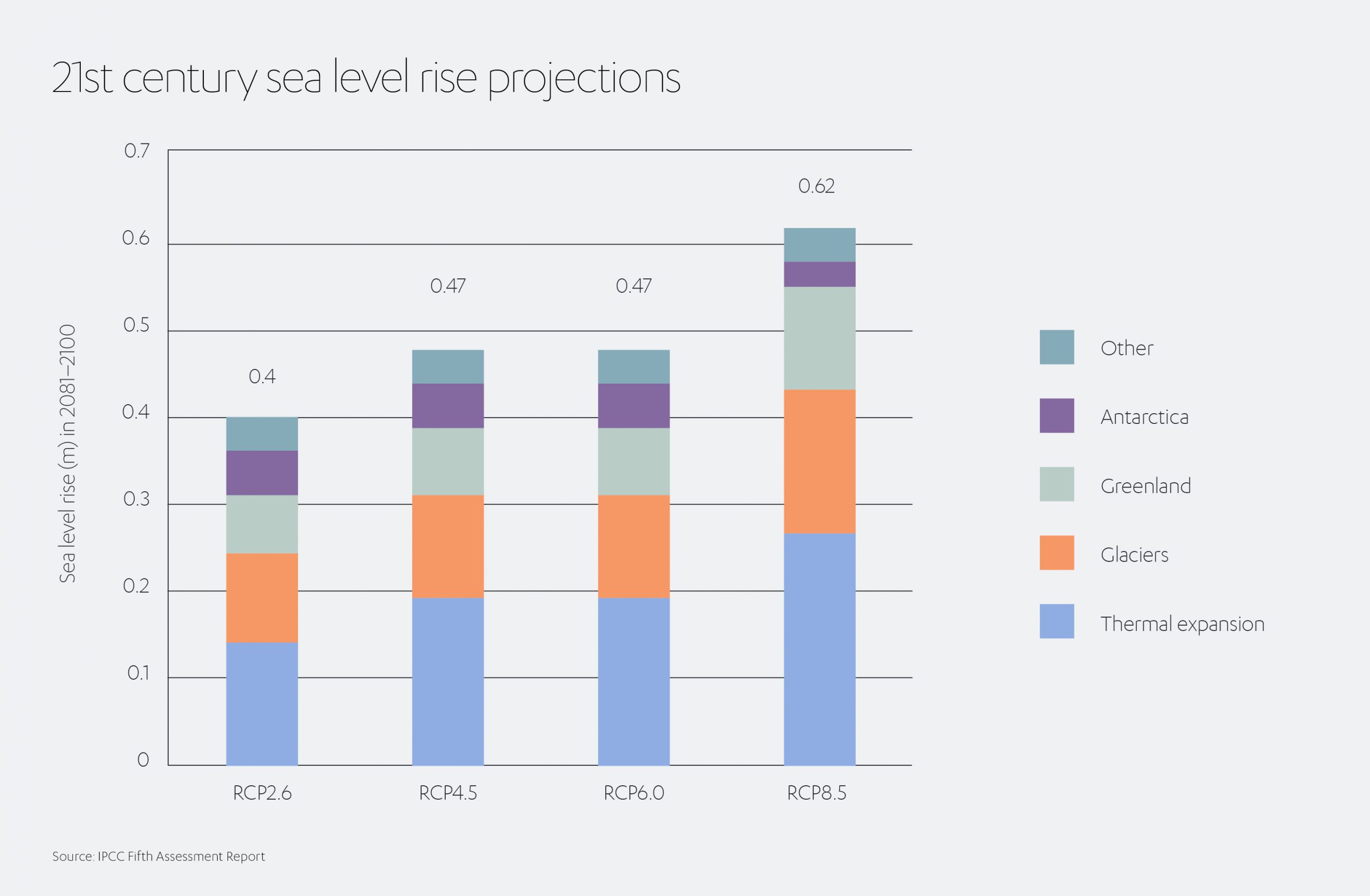

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), estimates that between 2081 and 2100, water temperatures could rise by between 0.40 and 0.63 degrees in low or high emission scenarios respectively[8]. From a scientific viewpoint, colder water can absorb more carbon dioxide (CO2). So as the oceans get warmer, they retain less CO2 – which means it stays in the atmosphere[9].

The same principle applies to our rising sea levels, caused by an increase in water volume. This temperature driven thermal expansion increases global sea water volumes even before additional volume from the melting of the polar icecaps is accounted for, which will cause sea levels to rise even further. And the issue is accelerating. Sea levels are thought to have risen by around 13-20 centimeters since 1900. By 2100, they are projected to rise between 30 centimeters and 1 meter[10].

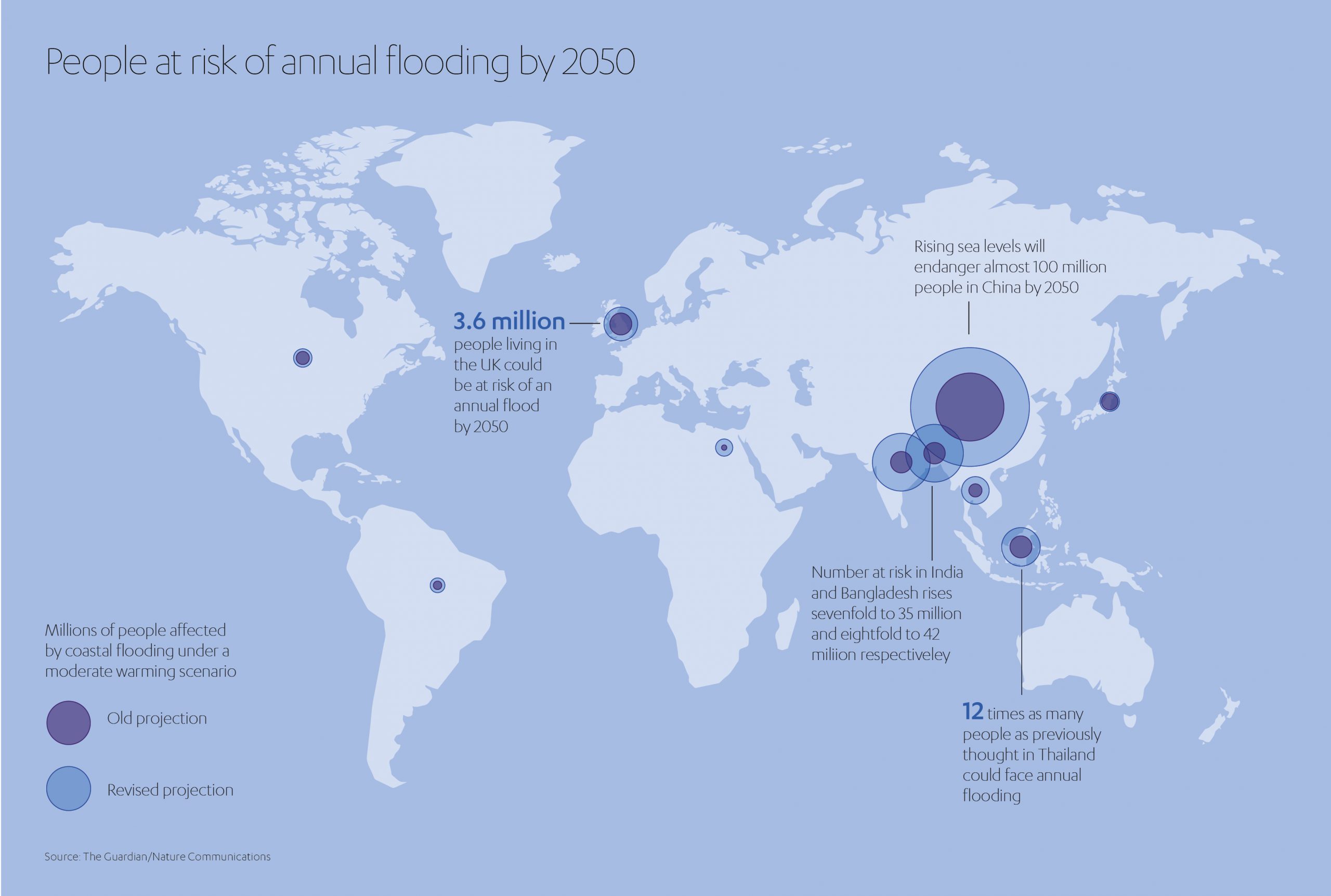

Already we are seeing the effects of rising sea levels through increased coastal flooding[11]. It is estimated that the 300 million people living in coastal areas globally will experience flooding at least once a year by 2050, unless carbon emissions reduce considerably, and coastal defenses are strengthened[12].

Climate Central has an interactive topological map model here, based on peer-reviewed scientific data to attempt to understand and quantify the areas at risk.

The protection of our coastal areas is also undermined by the depletion of coral reefs[13]. Hundreds of millions of people rely on coral reefs for essential nutrition, livelihoods, protection from life-threatening storms and crucial economic opportunity. They are a fundamental link in the marine food supply chain. According to WWF data, coral reefs occupy only 0.1% of the area of the ocean, but they support 25% of all marine species on the planet. In fact, the variety of life associated with coral reefs rivals that of the tropical forests of the Amazon or New Guinea[14].

The world’s largest coral reef system – the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia – comprises more than 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands spanning more than 2,300 kilometers. Like many of the thousands of reef systems around the world, it is also seriously endangered. Boston Consulting Group (BCG) estimates that without swift action, our oceans could be void of coral reefs by 2050[15].

For coastal-dwelling land creatures, rising sea levels mean surrounding freshwater areas are becoming more saline, putting the lives of species such as turtles and sea birds at risk[16]. This also has a significant impact on the availability of freshwater for human consumption.

Fishing for trouble

Rising sea temperatures are also having their effect on the fishing industry, as marine life migrates away from their natural habitats into colder waters. This means fishing fleets need to travel much further distances to secure their catch, spending more time and money – and as a consequence using more energy, pumping more fuel and carbon into the ocean and atmosphere. Some have resorted to using climate data to make their catches more effective. Others are moving into ‘aquaculture’ or ‘aquafarming’ (cultivating marine life under controlled conditions), or fish hatcheries (where fish are hatched and cared for, then released into natural waters)[17].

To exacerbate the situation further, 90% of our fish stocks are under threat, either by being fished to their maximum capacity or overfished[18]. Cod, swordfish and sharks are just some examples of species whose very survival is endangered. Fishing trawlers have come under particular scrutiny for their ‘dredging’ approach that catch large quantities of fish, with significant amounts then discarded. Trawlers also damage marine ecosystems, in what acclaimed marine biologist, Silvia Earle, has referred to as a ‘bulldozer’ approach. She suggests we need to be more conscious of the ‘real cost’ of our fishing activities and make better decisions[19].

The Marine Stewardship Council has developed a sustainable fishing model and what it describes as a science-based measurement standard for fisheries to follow. It suggests three measures for sustainable fishing:

- Fish at a level which can continue indefinitely and keep the fish population productive and healthy.

- Manage fishing activities to reduce their environmental impact and maintain the health of other species and habitats within the ecosystem.

- Fisheries should manage their operations in a way that complies with relevant laws and can adapt to changing environmental circumstances.

Plastic pandemic

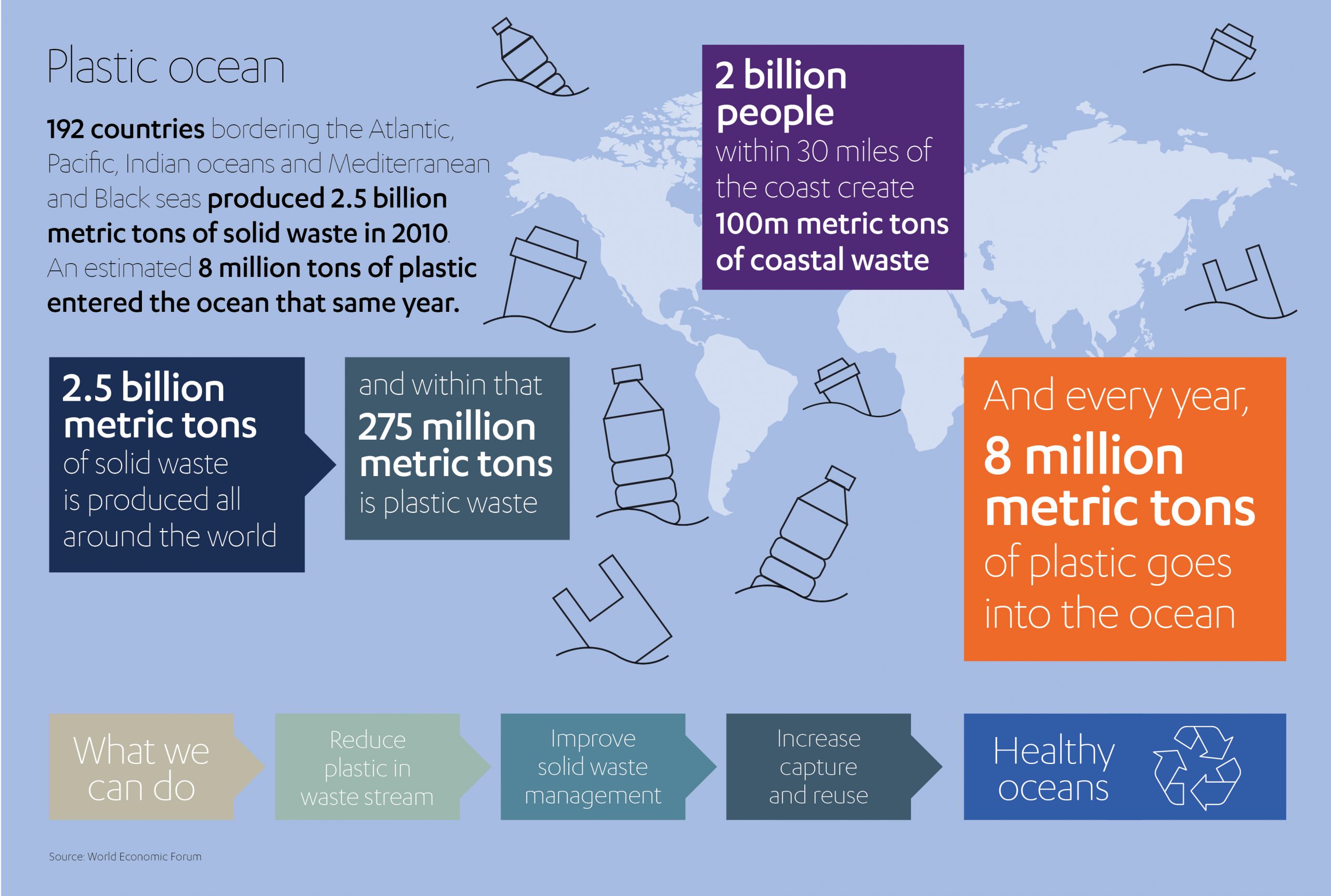

If the impacts of climate change is not enough, another unprecedent threat to the marine ecosystem is the huge amount of plastic waste which ends up in our oceans, estimated at around 150 metric tonnes in total worldwide[20] – currently around eight million tonnes a year. Around 80% of the volume comes from land-based sources through inadequate recycling awareness and collection. Plastic waste threatens an estimated 600 different ocean species, which often ingest it mistaking it for food[21]. There has also been an increasing concern about ‘microplastics’. These are tiny almost indiscernible plastic particles in the water that are ingested by marine life at all levels of the food chain including fish, which are then eaten by human and other land-based animals.

Consulting firm, McKinsey, estimates that based on current trends, this could increase to 250 million metric tonnes by 2025 — or one tonne of plastic for every three tonnes of fish[22]. It suggests a series of steps to combat the issue. They include setting meaningful and piloted waste management targets at government level, transferring best-practice global expertise to high-priority cities, ensuring the right project investment conditions, and equipping technology providers with detailed data to address the issue[23].

The business case for managing our marine environment

If you’re a skeptic, then perhaps the compelling reason to protect our ocean life comes down to basic economics. BCG describes the ocean as an “economic powerhouse” – effectively the world’s seventh largest economy worth more than US$24 trillion, not least in supporting livelihoods and creating jobs across areas such as fishing, tourism and shipping[24].

At the same time, more than two-thirds of the marine economy depends on maintaining healthy assets. BCG takes the Mediterranean Sea as an example, which touches 21 countries across Europe, Africa and Asia, supporting more than 150 million people along its coastlines.

Yet, while trillions of dollars in goods and services flow to and from our shores, our ocean assets remain exploited and depleting, it reports. By not addressing issues such as climate change, overfishing, and the depletion of marine habitats such as coral reefs and mangroves, we are “running down the ocean’s capital base”.

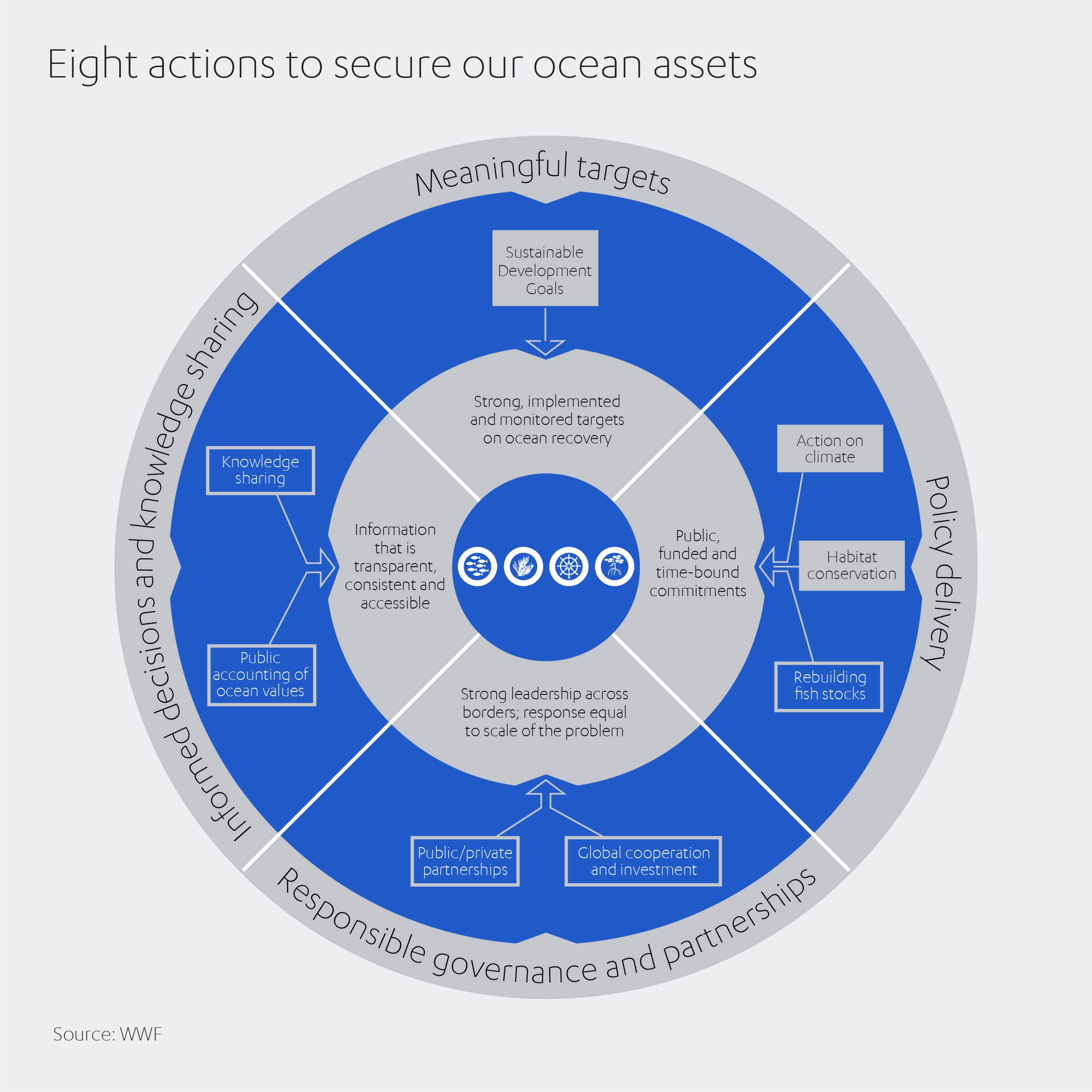

In its 2015 report, Reviving the Ocean Economy: A Case for Action[25], in collaboration with WWF, BCG had already proposed eight causes of action to cure ocean assets across the four pillars of ‘meaningful targets’, ‘policy delivery’, ‘responsible governance’ and ‘informed decisions and knowledge sharing’, shown below:

Shared seas

The UN Environmental Program is active in promoting the protection and sustainable management of the world’s marine and coastal environments. Its Regional Seas Program adopts a ‘shared seas’ approach – engaging neighboring countries to collaborate in taking specific actions to protect their common marine environment[26].

This is particularly prevalent when considering that most of the world’s ocean falls within international waters outside the national jurisdiction – or protection – of any particular country[27]. Today, more than 143 countries have joined 18 Regional Seas conventions and action plans in West Africa, East Africa, the Caribbean, Mediterranean, Northwest Pacific, East Asian Seas and Caspian Sea.

Recent initiatives under the UN scheme have included a project in Maputo, Mozambique, on the southeast African coast, where seagrass is essential for sustaining shrimps, sea cucumbers, clams and crabs – important sources of food and employment for the local community. Yet, through destructive shellfish harvesting, 86% of its seagrass meadows have been destroyed. A program, initiated by Eduardo Mondlane University and supported by the Mozambique government, is underway to educate the local community on non-destructive fishing practices that will also help to cultivate shellfish with the seagrass beds[28].

Known as the ‘Village of Coral’, Onna Village in Okinawa, Japan, is well-known for its reefs, attracting scuba divers from all over the world. While good for the economy, Onna Village’s tourist divers are less good for the reefs. In response, it has joined the UNEP lead ‘Green Fins’ code of conduct program, providing training and resources to dive and snorkel operators. The program started un 1999 by UK-based charity Reef World Foundation is running in conjunction with a local ongoing recovery project that has planted 30,000 corals[29].

Known as the ‘Village of Coral’, Onna Village in Okinawa, Japan, is well-known for its reefs, attracting scuba divers from all over the world. While good for the economy, Onna Village’s tourist divers are less good for the reefs. In response, it has joined the UNEP lead ‘Green Fins’ code of conduct program, providing training and resources to dive and snorkel operators. The program started un 1999 by UK-based charity Reef World Foundation is running in conjunction with a local ongoing recovery project that has planted 30,000 corals[29].

Agricultural practices and coastal developments are also depleting our mangrove forests, which are thought to be capable of storing up to four times more carbon than tropical forests for example. In certain areas such as Vietnam and India, more than 50% of the historical range of the mangrove forests have been destroyed[30]. Among the mangrove preservation projects underway is an initiative in Velondriake, Madagascar, to restore and conserve more than 1,200 hectares (almost 3000 acres) of forest[31].

As of January 2020, International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations have slashed allowable sulfur emissions from marine vessels in international waters from the previously allowed 3.5% down to just 0.5%. At more than 80%, it is the largest reduction in the sulfur content of a transportation fuel undertaken at one time[32]. This will significantly reduce the amount of sulfur oxides emanating from ships and should have major health and environmental benefits for the planet, particularly for populations living close to ports and coasts.

A collaborative effort

Turning around the collateral damage of the oceans caused so far will be no easy task. It will take a concerted effort of businesses, community leaders, consumers and government.

The UN-run Global Tourism Plastics Initiative has more than 450 signatories from businesses, governments, and other organizations to make concrete commitments to reducing plastics by 2025, through measures including eliminating unnecessary plastic packaging, moving from single-use to reusable plastics, enduring all plastic packaging is recyclable or compostable by 2025, and report publicly and annually on their progress[33].

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an environmental body with around 1,300 member organizations across government bodies, non-government organizations and business association and academic organizations[34]. At its World Conservation Congress in 2016, its members approved a resolution to protect 30% of the planet’s ocean by 2030. It calls for support for scientific research to analyze and monitor the impacts of climate change and use the knowledge to implement appropriate mitigation strategies[35]. The next event, which takes place every four years, is scheduled for June 2020.

At a personal level, I am proud that Abdul Latif Jameel – through Almar Water Solutions – is helping to address some of the issues around the availability and security of freshwater supplies to communities across the globe.

Almar Water Solutions is a specialist provider of technical capabilities for water infrastructure development, including design, financing and operation. It has proven to be the ideal complement to Fotowatio Renewable Ventures, the renewable energy arm of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy.

In January 2019, Almar Water Solutions was awarded the contract in Saudi Arabia to develop Shuqaiq 3 IWP, one of the world’s largest reverse osmosis desalination plants. Situated near the Red Sea city of Al Shuqaiq, a US$ 600 million investment will fund the development of a plant covering the size of 34 soccer fields. When it is completed in 2021, it will deliver 450,000m3 of clean water each day on a 25-year build-own-operate scheme with WEC. More than 1.8 million people will receive fresh water from the site, while 700 jobs will be created.

News of our involvement came less than eight weeks after we were awarded the contract to produce Kenya’s first large-scale desalination plant. Once operational, the site will deliver 100,000m3 of drinking water to more than one million people in Mombasa, on Kenya’s coastline, where a severe water crisis has caused interruptions in supply for several years.

The solution starts on land

As mentioned above, more than 80% of ocean pollution is from land-based activities. As well as plastics, these include urban discharges, coastal developments, the agricultural runoff of pesticides and discharge from factories and industrial plants[36], [37].

National Geographic estimates that US water sewage treatment plants discharge twice as much pollutants than oil tankers. Another menace, it continues, are the poisonous algae and plants that enter harbor waters. It suggests solutions such as establishing marine parks to protect biodiversity, reducing trawler fishing practices, minimizing the military sonar that harm or kill species such as dolphins and whales, and helping fishers to use conservation methods while still preserving their livelihoods[38].

The solutions are complex. But protecting our oceans should be one at top of the global climate change agenda – not least in terms of our food and water security. Our current global population of 7.6 billion will reach 9.8 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100, and for many communities – particularly in poorer countries – our seas still provide a primary source of food, nutrition and job creation. And while the ocean has historically been seen as one of the most effective ways to capture carbon, it is now reaching its limits and needs to be urgently preserved.

I am hopeful that by working together with businesses, governments, NGOs and communities in a spirit of collaboration and action, we can save our oceans before it is too late.

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/06/three-ways-can-save-worlds-oceans

[3] https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/11/Seafood_Scoping_Report_EAT-Lancet.pdf

[4] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/ocean-and-climate-change

[5] https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/quick-questions/why-are-coral-reefs-important.html?gclid=Cj0KCQjw09HzBRDrARIsAG60GP9hNeNmABUXeDcVs2NiWNvNQJXEEuprOW5-Zs00HmfkK_wmQOvu8k0aAopVEALw_wcB

[6] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/06/challenges-worlds-oceans

[7] https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/wwf/emergency-recovery-plan-could-halt-catastrophic-collapse-worlds-freshwater-biodiversity

[8] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/ocean-and-climate-change

[9] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2017/feb/16/scientists-study-ocean-absorption-of-human-carbon-pollution

[10] https://ocean.si.edu/through-time/ancient-seas/sea-level-rise

[11] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-51283716

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/29/rising-sea-levels-pose-threat-to-homes-of-300m-people-study

[13] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/ocean-and-climate-change

[14] https://wwf.panda.org/our_work/oceans/coasts/coral_reefs/

[15] https://www.bcg.com/en-gb/publications/2017/transformation-sustainability-economic-imperative-to-revive-our-oceans.aspx

[16] https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2018/05/rising-sea-levels-putting-wildlife-at-risk/

[17] https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/03/ocean-fish-swim-away-from-warming-waters/

[18] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/07/fish-stocks-are-used-up-fisheries-subsidies-must-stop/

[19] https://marinebio.org/interview-with-dr-sylvia-earle/

[20] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/saving-the-ocean-from-plastic-waste

[21] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/we-can-stop-choking-our-oceans-with-plastic-waste-heres-how/

[22] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/saving-the-ocean-from-plastic-waste

[23] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/saving-the-ocean-from-plastic-waste

[24] https://www.bcg.com/en-gb/publications/2017/transformation-sustainability-economic-imperative-to-revive-our-oceans.aspx

[25] https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/reviving-the-oceans-economy-the-case-for-action-2015

[26] https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/oceans-seas/what-we-do/working-regional-seas/why-does-working-regional-seas-matter

[27] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/06/three-ways-can-save-worlds-oceans

[28] https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/saving-mozambiques-seagrass

[29] https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/village-coral-moves-protect-its-namesake

[30] https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/wwf/climate-crisis-mangroves-bring-massive-benefits

[31] https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/greening-blue-championing-coastal-climate-solutions

[32] https://www.woodmac.com/nslp/imo-2020-guide/

[33] https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/tourism-tackle-plastic-pollution-new-commitment

[35] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/ocean-and-climate-change

[36] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/ocean-threats/

[37] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/ocean-and-climate-change

[38] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/ocean-threats/

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit