Food for thought

How the Jameel Family is supporting the shared vision of the UN in eradicating poverty and ending hunger.

Since the very beginning, Abdul Latif Jameel has always been more than a business.

Our late founder, Sheikh Abdul Latif Jameel, was himself born in a developing country which – pre-oil – knew more than its fair share of poverty and hunger.

Having seen at first-hand the impact this had on communities across the Middle East and North Africa, he instilled from the outset, in the business and in his family, a strong sense of active philanthropy and a vision to create a better, more inclusive, society.

In the decades that followed, through both the business activities and what is today, known as Community Jameel, we have remained true to that spirit, helping to create opportunities, reduce hunger, tackle poverty, and set people, and communities, on the path to economic independence.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that the first two sustainable development goals are also two of the primary areas of action for the Jameel Family: SDG1 – eradicating poverty and SDG 2 – ending hunger.

Despite the progress made towards these objectives over the three-quarters of a century since both the UN and Abdul Latif Jameel were founded, never has action been more needed.

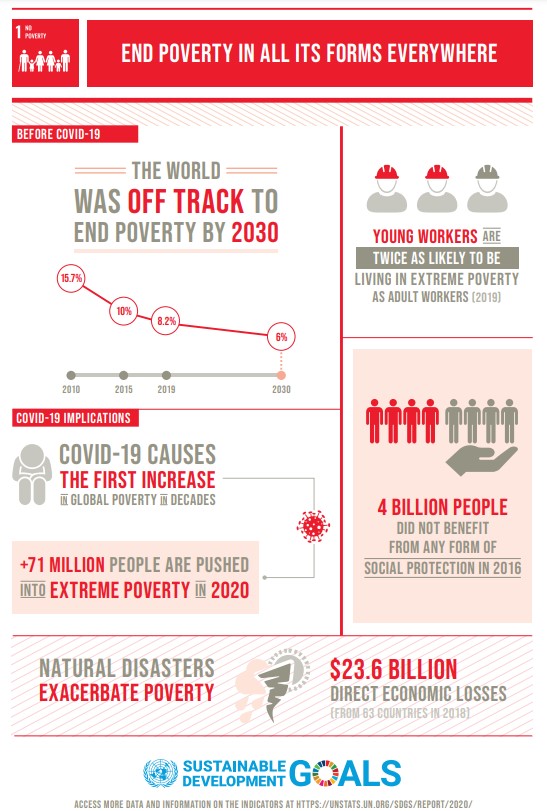

Efforts to eradicate poverty

Poverty is more than simply a lack of income and resources. It includes hunger and malnutrition, limited access to education and other basic services, social discrimination and exclusion, as well as the lack of participation in decision-making. And in 2020, for the first time in a generation, global extreme poverty increased, driven by a deadly combination of conflict, climate change and COVID-19[1].

Even before COVID-19, estimates suggested that 6% of the global population would still be living in extreme poverty in 2030, missing the SDG target of ending poverty.

Since the pandemic, around 120 million additional people are living in poverty, according to World Bank data, with the total expected to rise to about 150 million by the end of 2021[2]. The scale of the problem is evident in some painful facts[3]:

- around 80% of people living below the international poverty line live in rural areas

- half of the poor are children

- a majority are women

- more than 40% of the global poor live in countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence – a figure that is expected to rise to 67% within the next decade

- around 132 million of the global poor live in areas with high flood risk

The official UN definition for SDG 1 is to: “Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programs and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions.”

The SDGs also aim to create sound policy frameworks at national and regional levels, so that by 2030, “all men and women have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance.”[4]

These are undoubtedly laudable aims which we can all support, but well-meaning words and worthy policies are not enough to drive real change.

For change to occur, words, ambitions and policies must translate into effective action on the ground.

Nobel-Prize-winning innovation

The need to ensure that policies to tackle poverty are implemented as effectively as possible is one of the core aims of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, or J-PAL.

The need to ensure that policies to tackle poverty are implemented as effectively as possible is one of the core aims of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, or J-PAL.

The Poverty Action Lab was founded in 2003 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) by professors Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, with the goal of transforming how the world approaches the challenges of global poverty. In 2005, the lab was renamed as the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, beginning a close collaboration with Community Jameel.

J-PAL is a global research center working to reduce poverty by ensuring that policy is informed by scientific evidence. Anchored by a network of 227 affiliated professors at universities around the world, J-PAL conducts randomized impact evaluations to answer critical questions in the fight against poverty. To-date, J-PAL has touched the lives of over 400 million people.

Examples of J-PAL-affiliated projects include research into the impact of job networks on women’s recruitment in Malawi, and evaluation of a program to understand the impact of a universal basic income during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya.

In October 2019, two of J-PAL’s cofounders, Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, along with one of its original affiliated researchers, Michael Kremer, were awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty. Esther is the youngest winner of the Prize, and only the second woman to receive the award.

Talking about the collaboration with the Jameel family, Esther commented, “Mohammed Jameel saw in us…and in our project, something that could make a difference, and decided to risk his reputation and his money, behind that. This would never have happened without the ecosystem and his vision and commitment for the World’s poor, which was apparent then, and [is] still important today.”

Halting the spread of hunger

The challenges of poverty are often inextricably linked to issues around hunger (SDG 2 – ending hunger), as food is often one of the vital resources lacking for people who live in poverty. And in a world that is becoming more populated, more developed, and more urbanized, the pressures on the productivity, accessibility, and sustainability of food and agriculture systems are only going to intensify. Add in the effects of climate change, and these threats to the world’s agriculture and food supplies are compounded.

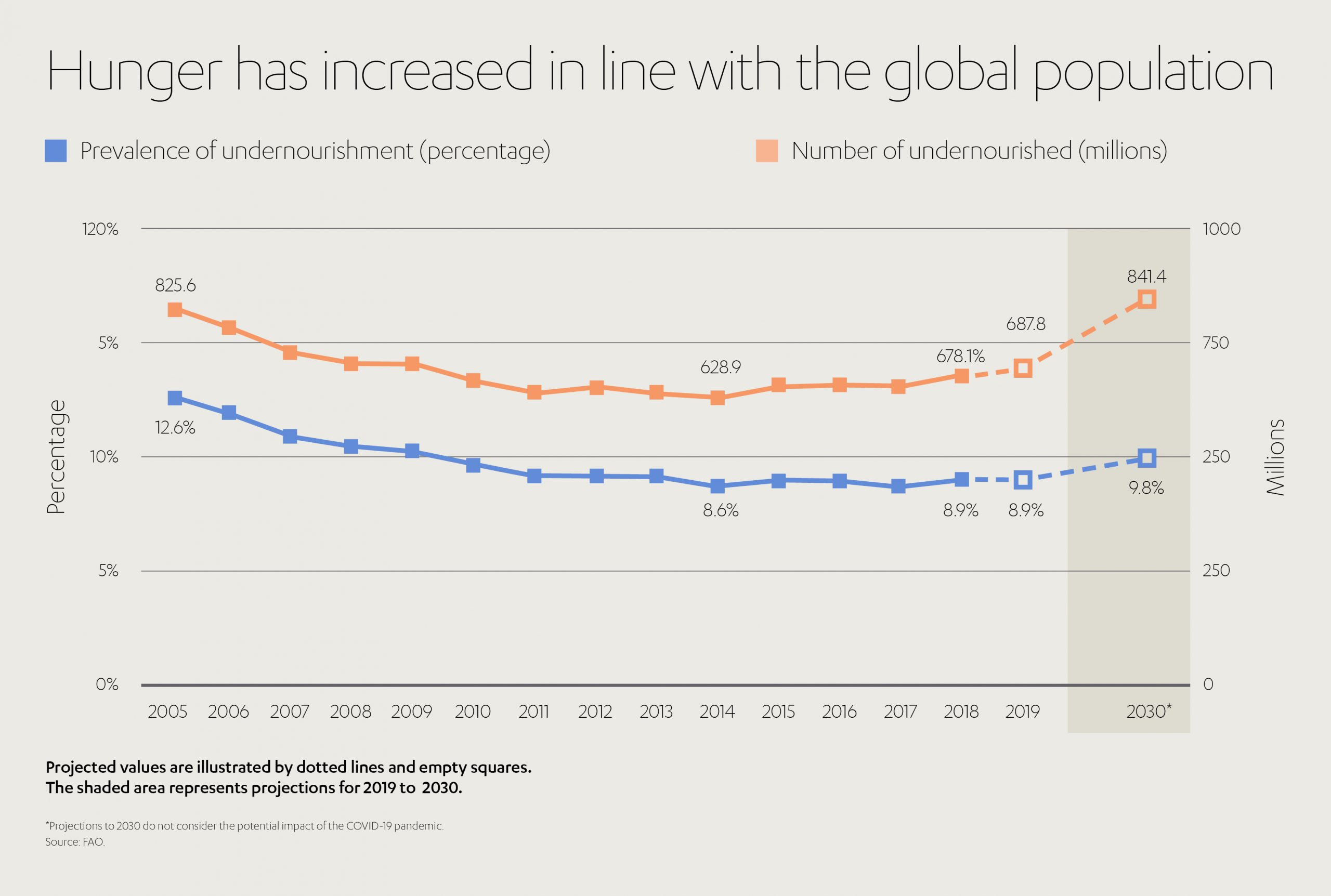

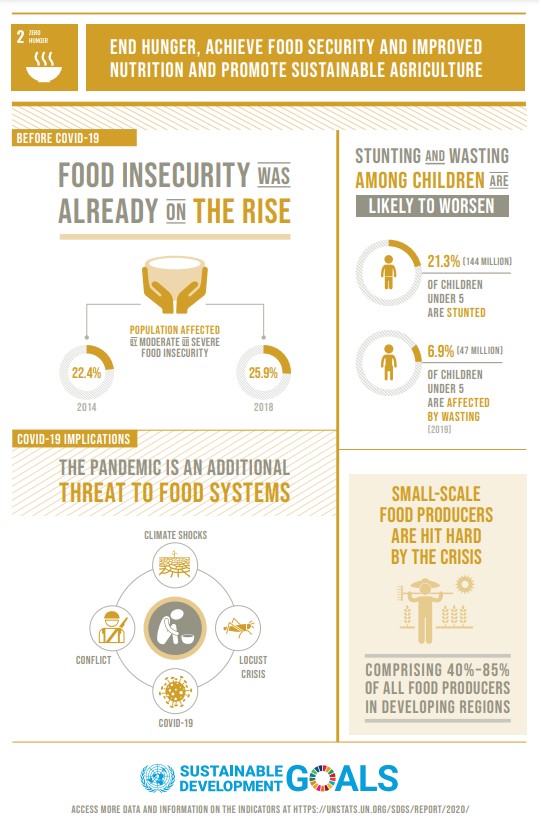

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN estimates that almost 690 million people went hungry in 2019. This represents an increase of 10 million on 2018, and of almost 60 million in five years[5].

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN estimates that almost 690 million people went hungry in 2019. This represents an increase of 10 million on 2018, and of almost 60 million in five years[5].

High costs and low affordability also mean billions pf people that do have access to food, cannot afford to eat healthily or nutritiously, while the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic could tip an additional 130 million more people into chronic hunger by the end of 2021.

The largest number of undernourished people (381 million) live in Asia. Africa is second with 250 million, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean at 48 million. The global prevalence of undernourishment – or overall percentage of hungry people – has remained relatively stable in recent years at 8.9%, but absolute numbers have been rising since 2014. In short, this means that in the last five years, hunger has increased in line with the global population[6].

Tackling global hunger is another long-standing focus of the Jameel Family and its support for programs, people and projects that can make a tangible difference to those most in need.

J-PAL itself has a specific agriculture program that focuses on improving agricultural systems in developing countries. This includes evaluating strategies to help farmers adopt practices and technologies that are profitable or environmentally sustainable, and programs that have the potential to better link farmers to markets

J-WAFS in the vanguard

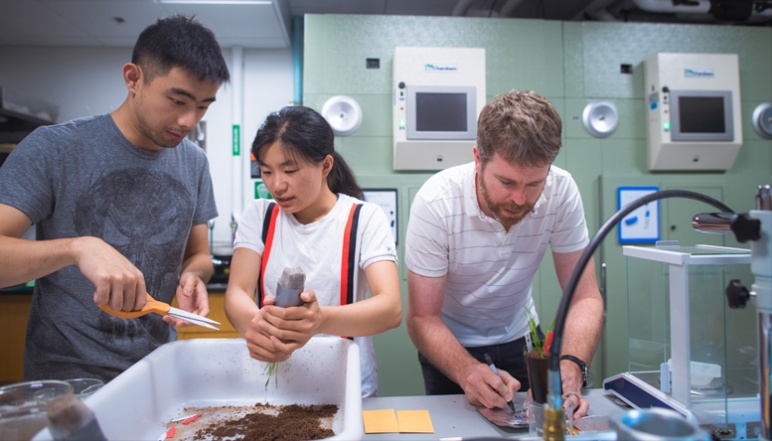

One of J-PAL’s sister labs at MIT is the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food and Systems Lab (J-WAFS), which supports research, innovation and technology to ensure safe, resilient food and water supplies with minimal environmental impact.

One of J-PAL’s sister labs at MIT is the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food and Systems Lab (J-WAFS), which supports research, innovation and technology to ensure safe, resilient food and water supplies with minimal environmental impact.

The gravity of the challenges to our global food system drives J-WAFS’ Institute-wide, solutions-oriented approach to research and innovation. To ensure safe and resilient food supplies now and into the future, J-WAFS catalyzes new research, leads transdisciplinary studies, supports commercialization efforts, and fuels cross-institutional collaborations. The results include policy and technology innovations, supply chain interventions, new food safety technologies, and many more. Since its founding in 2014, it has funded more than 60 projects, generating more than US$ 12 million in follow-on funds to extend and expand their J-WAFS research[7].

Much of this research is focused on innovative techniques to improve, and ideally transform, the efficiency and effectiveness of food and water systems in developing countries at a cost that makes them accessible and economically viable to all.

In Kenya, for example, J-WAFS is supporting a project led by MIT professors Daniel Frey and Leon Glicksman to develop clay pot evaporative cooling chambers to preserve fruit using natural water evaporation, without the need for electricity.

In hot and dry regions, the absence of temperature-controlled storage facilities, and little-to-no access to electricity, means that fruit and vegetable crops deteriorate quickly. By providing the correct low temperature and high humidity conditions, clay pot evaporative chambers have been successful in preserving produce and bringing it to market. Suitable storage also provides farmers with the economic flexibility to wait for the right price conditions before releasing their products, should market prices be low at the time of production.

Another J-WAFS supported project is being led by MIT professors David Des Marais and Caroline Uhler, who are studying ways to genetically strengthen crops to withstand some of the uncertainties of climate change, such as unpredictable rainfall. Crops in even moderate drought conditions will drop their leaves and abort their seeds, thereby destroying any chance of recovery for that season, even if it rains a few days later. Des Marais’ research is looking at how crops could be engineered at the molecular level to handle a short-term drought, but also be able to thrive in wet conditions when the rain returns.

This project, marrying molecular biology and machine learning to help the world’s food supply adapt to climate change, is illustrative of the types of boundary-pushing endeavors J-WAFS was created to support. “J-WAFS lets us take those ideas that are good, but maybe not quite ready to take to market, and try them out in a pretty low-stress setting,” said Professor Des Marais.

Carole Uhler was equally positive in her support of J-WAFS: “Now that we have some proof of concept, we can push this further. That’s the really exciting thing about a J-WAFS grant. We couldn’t have done this work otherwise.”

Professor Tim Swager, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Chemistry at MIT, is also leading exciting J-WAFS supported research to develop fast, easy, and affordable food safety sensing technology. The research is based on specialized droplets — called Janus emulsions — that can detect bacterial contamination in food and liquids. The technology could have huge benefits in less developed countries, as it can be applied to drinking water and all sorts of foods.

Metastasis in cows, for example, is a big problem for milk producers all over the world and can spread quickly through entire herds. India is a case in point. Milk from multiple herds will often be combined at a central regional collection point. If one herd has metastasis, the entire batch is spoiled and must be disposed of. Swager’s technology would be able to identify metastasis in an affected herd before it contaminates unaffected milk, thereby reducing wastage.

Metastasis in cows, for example, is a big problem for milk producers all over the world and can spread quickly through entire herds. India is a case in point. Milk from multiple herds will often be combined at a central regional collection point. If one herd has metastasis, the entire batch is spoiled and must be disposed of. Swager’s technology would be able to identify metastasis in an affected herd before it contaminates unaffected milk, thereby reducing wastage.

This exciting technology has already spun-out of the lab as part of the J-WAFS Solutions Program and the startup company, Xibus Systems, is developing protocols for field tests. The goal is to provide a simple, fast, robust system that requires minimum training and will not disrupt the producer’s current way of working.

This exciting technology has already spun-out of the lab as part of the J-WAFS Solutions Program and the startup company, Xibus Systems, is developing protocols for field tests. The goal is to provide a simple, fast, robust system that requires minimum training and will not disrupt the producer’s current way of working.

The benefits of innovations such as these is still small at the moment, but the potential is huge. The Jameel Family is committed to investing the resources and the know-how to exponentially increase their scale and their impact on the journey towards the UN SDGs.

The global scale of these problems is clear, and despite the unprecedented wealth of our society, they are still among the very greatest challenges we face. To solve them will take a strategic and unified effort. But it is an effort we must make to secure a sustainable, viable future for our communities.

Through both our business portfolio and Community Jameel initiatives, and by working together with partners in the public, private and third sectors, we are proud to be taking action to help achieve this.

Learn more about how the Jameel Family’s activities are contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals by visiting: https://jameel75.com/sdg to watch our video and download a summary report.

[1] Poverty Overview (worldbank.org)

[2] Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: Looking back at 2020 and the outlook for 2021 (worldbank.org)

[3] Poverty Overview (worldbank.org)

[4] Ending Poverty | United Nations

[5] State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, FAO, March 20201.

[6] State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, FAO, March 20201.

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit