Improving healthcare access in developing markets

From a longer-term historical perspective, the world we live in is undoubtedly fairer than it has ever been versus, say 100 years ago. In many – if not the majority – of countries across the globe, populations are richer than in the past, there is a universal respect for human life, and there is a growing appreciation of equal opportunities, recognized by everyone from societies and governments down to individuals.

It is perhaps all the more disturbing, and a stark contrast therefore, that with economic globalization, the inequality between richer and poorer appears to be growing[1] and that, in every corner of our planet, whole communities are denied access to that most basic of human needs – healthcare – some voices that say that access to which should be a basic human right; simply due to their birthplace, access to infrastructure or lack of wealth. Nonetheless, life expectancy has increase and infant mortality has decreased globally.

And yet, for large swathes of humanity, this is the every-day reality. Superficially, the effectiveness, sophistication and accessibility of our healthcare systems are unparalleled, particularly in developed markets such as North America, Europe and the Far East. But dig a little deeper beneath the surface of global healthcare and there are some unpalatable truths.

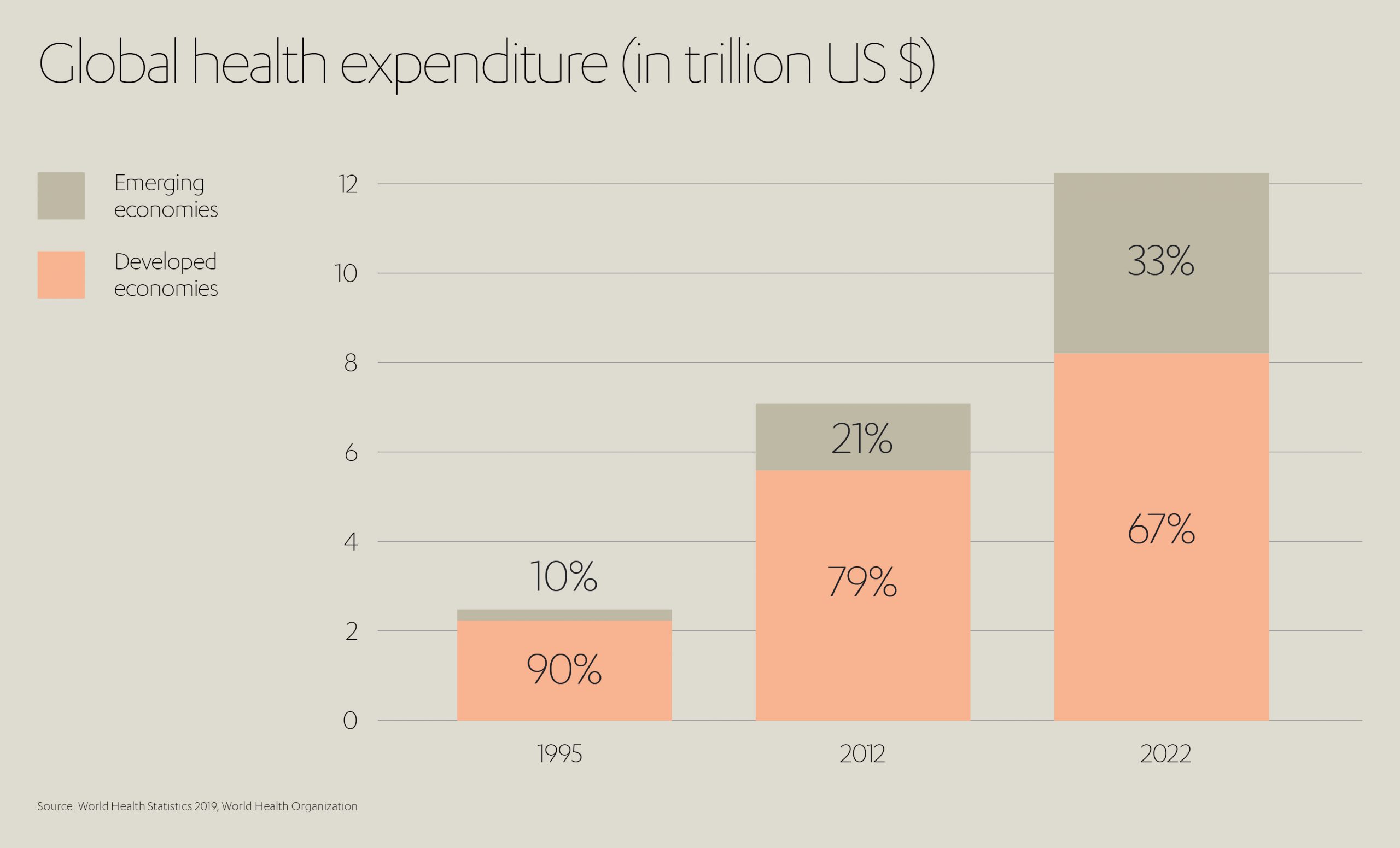

As a snapshot of shame, the data is compelling:

- Africa averages one doctor per 3,324 people, compared to one per 293 in Europe.

- Average life expectancy in the Central African Republic is 53 years (with 45 years of ‘good health’) compared with 82 (and 72 years of ‘good health’) in the Netherlands.

- Africa’s HIV infection rate is more than five times that of Europe.[2]

- Only 33% of people in Africa and 45% of people in South East Asia have access to sanitation systems, compared with 93% of Europeans.[3]

- Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 15 times more likely to die before the age of five than children in high income countries.

- The maternal mortality ratio of developing regions is 14 times higher than in developed regions.[4]

Medical journal The Lancet’s latest Healthcare Quality and Access Index underscores this gulf, measuring preventable mortality rates across 195 countries from 1990 to 2015. The research shows that while the average global index score rose during this period from 40.7 to 53.7, the range actually increased. By 2015, it spanned from 28.6 (Central African Republic) to 94.6 (Andorra).[5] The healthcare indexes of several countries across southern sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and South Asia lagged behind their corresponding socio-demographic indexes (SDI), suggesting a lack of focus on healthcare and missed opportunities for improvement along the way.

To improve the outlook for those populations disadvantaged in this way – to bring us closer to the promised land of health equality – we must first diagnose the true nature of the problem.

Only by understanding the root causes and key challenges, can we identify potential opportunities for addressing the issues at source and work toward reforms in policy and practice that make a real-world and sustainable difference.

Far, far away – the geographic obstacle

Central to the global healthcare conundrum is the question of access. In other words, bringing people into contact with the expertise, facilities and treatments they need.

As far back as 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed a resolution to provide affordable healthcare coverage (specifically: information, prevention, medication and rehabilitation) for all people. This has, so far, met with only partial success because the reasons for uneven health access are many – and not all can be circumvented simply by an injection of money.

One of the primary barriers to health access is geographical. Some of the poorest, or at least most unequal, countries in the World are also the largest. India covers some 3.287 million km2, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2.345 million km2, China 9.597 million km2, Brazil 8.516 million km2.

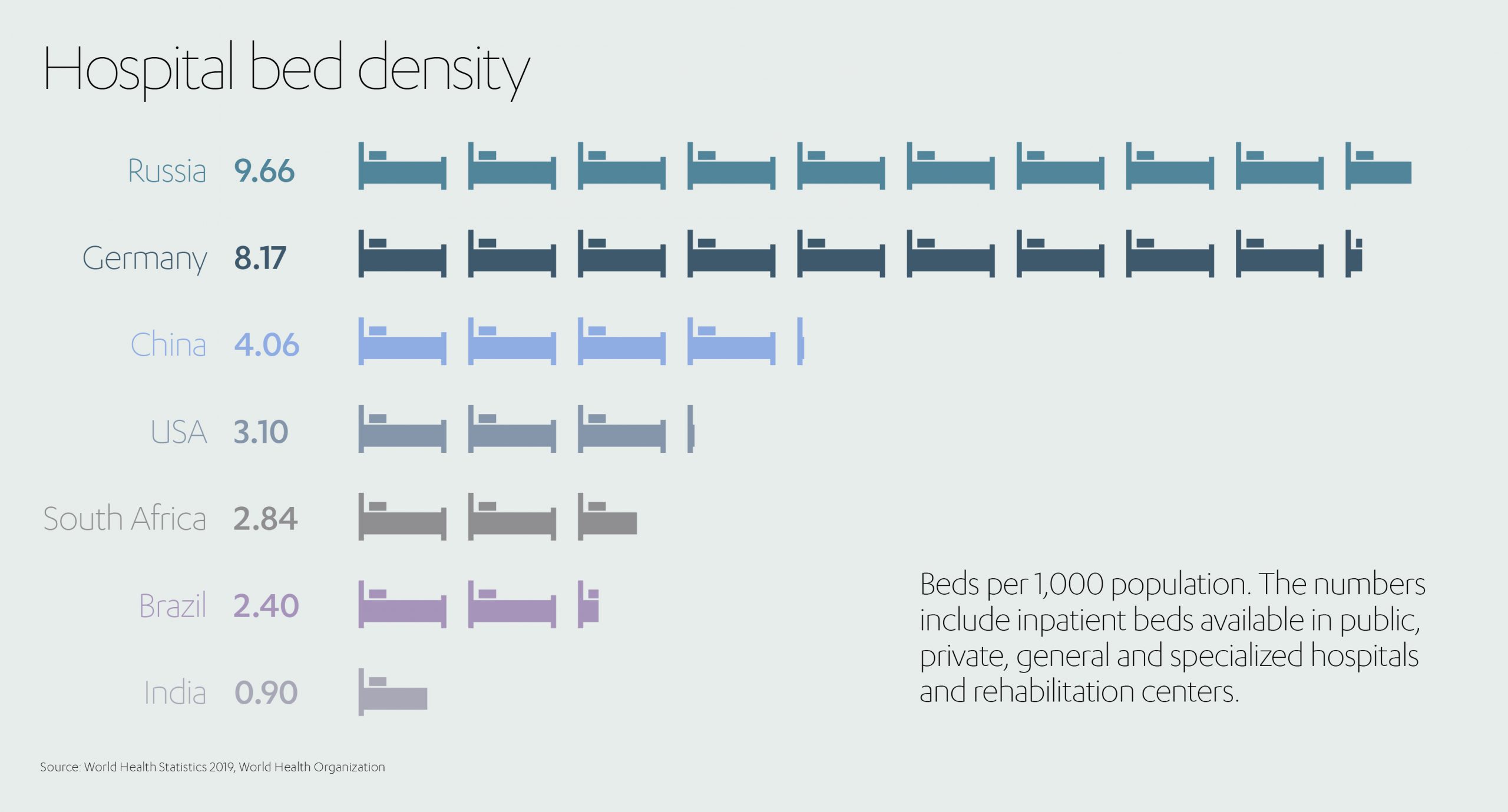

These enormous countries are characterized by widely dispersed populations often separated by great distances from their nearest points of primary healthcare. This remoteness only compounds the problem of emerging economies having far fewer medical resources to begin with. Consider, for example, the fact that Germany has 8.17 hospital beds per 1,000 people while China has just 4.06, South Africa 2.84, Brazil 2.4, and India 0.9.[6]

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 287 million people (including 64 million women of child-bearing age) live more than two-hours’ transport time from the nearest hospital. Two-thirds of sub-Saharan countries fail the global target of 80% of people living within two-hours of a hospital, while in South Sudan (average life expectancy: 59 years[7]) only 22.8% of people meet that criteria.[8]

A sobering thought, given that it is estimated around half of all deaths (and a third of disabilities) in low and middle-income countries could be avoided if people had ready access to emergency healthcare.[9]

It might be reachable – but is it available?

Even if a sick or injured person reaches a hospital or healthcare center, the struggle to access treatment in a developing economy can be far from over.

A report compiled by the WHO attempts to explain shortcomings around healthcare availability in low-income countries spanning Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.[10] It highlighted a long list of issues to overcome, including:

- A shortage of trained health workers, equipment and medicines

- Limited opening hours and high staff absenteeism

- Unsustainable waiting times

- Variable quality of drugs and medical aids

- Inadequate information for patients on healthcare choices

- Poor or late referrals

Low-income countries further suffer from poor integration of health strategies at the local, regional and national level. Lacking a cohesive, holistic approach, opportunities for complementary programs and joined-up thinking are missed, with often disastrous results. This is most graphically evidenced in one of medicine’s most proven life-savers – access to vaccinations.

One study into vaccinations (for tuberculosis, diphtheria, tetanus and measles) covering Bangladesh, Benin, Brazil, Cambodia, Eritrea, Haiti, Malawi, Nepal, and Nicaragua makes for alarming reading.

In Cambodia, it was found that less than 1% of children received all available vaccinations and almost one-in-five received no vaccinations at all. Within the poorest wealth quintile of Haiti, 15% of children received no interventions at all and 17% only one intervention. Even in Nicaragua, which recorded the most promising statistics among the countries surveyed, only 13.3% of children received all their vaccinations.[11]

Clearly much input is needed, both monetarily and organizationally, to ensure healthcare isn’t just accessible but also available. How else can we hope to narrow the gulf between low-income and developed countries?

The impact of healthcare on economic development

Ensuring the availability of effective healthcare is not only essential for the health of individuals, but also for the economic ‘health’ of the countries they live in. As the WHO states, better health “makes an important contribution to economic progress, as healthy populations live longer, are more productive, and save more.”[12]

The relationship between health and economic growth has been examined extensively. In one study published in the Journal of Health Economics, for example, the economic performance of developing countries increased significantly with an improvement in public health[13]. Another showed that an annual improvement of one year in life expectancy increases economic growth by 4%[14].

As far back as 2001, the WHO established the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (CMH) to analyze the impact of health on development and seek ways in which health-related investments could advance economic growth and equity in developing countries.

In the executive summary of its concluding report, the CMH recommends that “low and middle-income countries, in partnership with high-income countries, should scale up the access of the world’s poor to essential health services.” It also highlights the urgent need for “greater investments in new and improved technologies to fight killer diseases” and a “significant scaling up of financing for global R&D” in healthcare.

What price quality healthcare?

Whether the cost of healthcare is met by the individual or the state, all treatments and drugs carry a price. So, in many ways the fight for global access to healthcare mirrors the fight against global poverty.

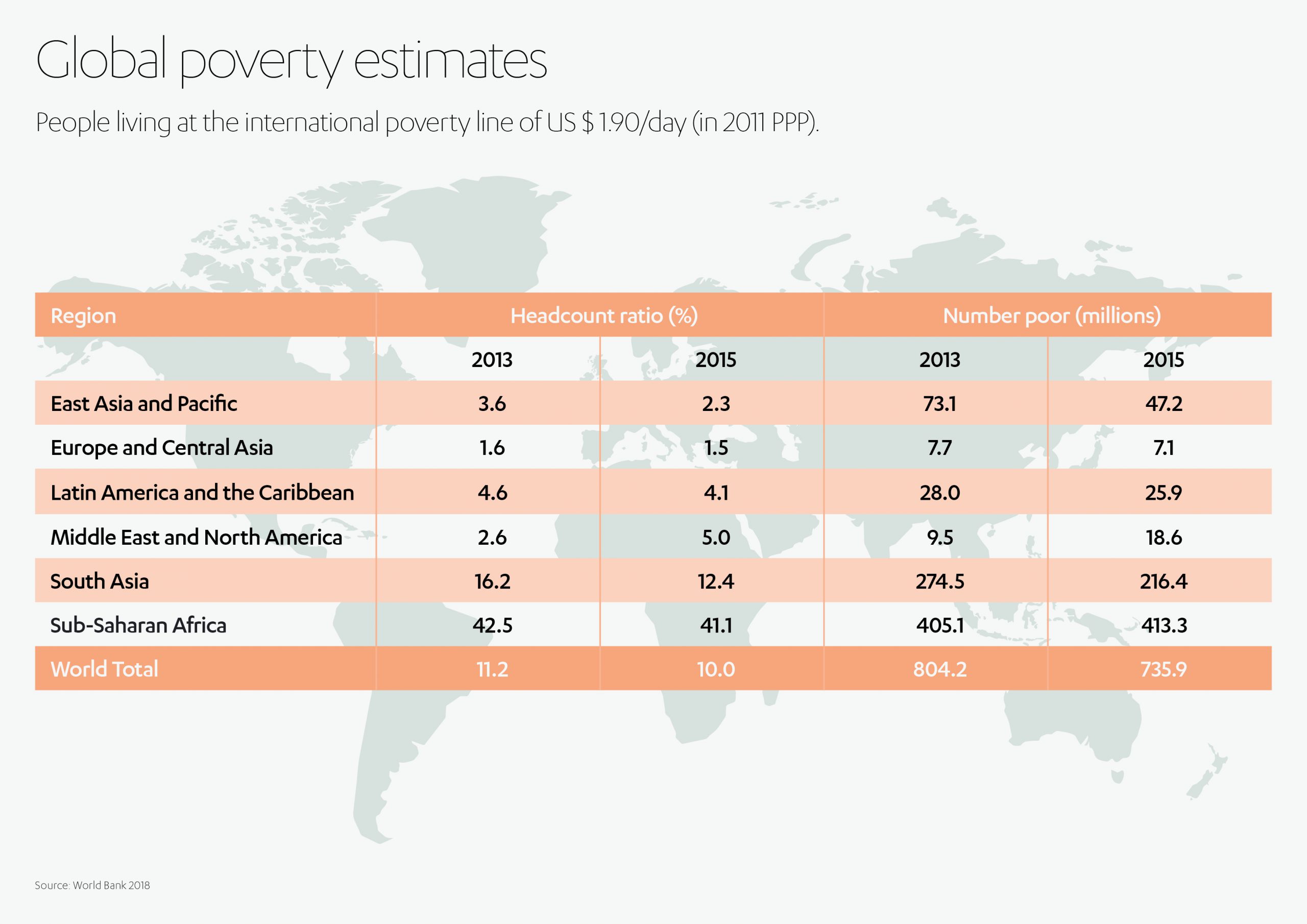

And here, there is still much progress to be made. World Bank data shows some 10% of the World’s population (or 734 million people) living on less than US$ 1.90 per day (the criterion for poverty).[15] While the poverty trend had been heading downward in recent years, the COVID-19 crisis is expected to drag a further 40-60 million people worldwide into poverty during 2020.[16]

Presently, 4.1% of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean (or 25.9 million people), 5% of the population of the Middle East and North Africa (18.6 million people), 12.4% of the population of South Asia (216.4 million people) and 41.1% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa (413.3 million people), live in poverty.

Of the 46 African countries deemed ‘sub-Saharan’ by the UN Development Program, 39 (excluding only Eritrea, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Gabon, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia) fail to provide citizens with universal healthcare. Nor does India, with its 1.35 billion people, nor Vietnam, Cambodia or Indonesia in South East Asia.[17]

For largely agrarian societies, common in the developing world, cash flow is highly dependent on time of year and the availability of produce to sell for cash. In one study, rural Cambodians were shown to be more likely during rainy season to resort to over-the-counter drugs rather than purchase pricier face-to-face treatments.[18]

One must also look beyond the direct costs of drugs or treatments. For anyone existing on or near the poverty line, transport costs to hospitals or clinics will be an obstacle too far, to say nothing of loss of earnings while absent from home and work.

All of which can feed into a particularly vicious circle. Researchers in India found an incidence of 1.2 illnesses a month per poor household, with the cost of treating illnesses identified as causing 85% of all cases of impoverishment. [19]

It is clear that poverty represents an immediate and lasting barrier to accessing healthcare for a dispiriting proportion of people globally.

Beyond poverty, we have the constant which underpins all issues governing access to healthcare – the human factor.

Cultural and human barriers

People, and the societies in which they flourish or falter, must also be considered as part of the access to healthcare equation. Here, divergences between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ countries can emerge even in the formative years of life. The great divider? Education.

Education is pivotal not just to knowledge but to self-awareness. Without an appreciation of one’s fundamental right to health (or the scope of interventions available to improve or prolong life) one cannot assert one’s right to wellbeing.

Research once more exposes startling inequalities.

Data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics shows that in Uganda (life expectancy: 62 years) only 12% of the poorest 14-16 year olds have completed primary school; in Pakistan (life expectancy: 67 years) just 20% of 20-22 year olds have finished secondary school; in Afghanistan (life expectancy: 63 years) just 33 females complete lower secondary school for every 100 males; and in Yemen (life expectancy: 65 years) only 21% of the poorest young women can read.[20],[21]

Later in life, this imposed ignorance can manifest in a number of damaging ways.

Among them is low self-esteem, as evidenced by one study in Laos correlating lack of assertiveness among lower-income communities with difficulty accessing qualified doctors and navigating complex medical billing systems.[22] The data also reveals a lack of trust, both of health professionals and of intermediaries such as insurers, evident within villages of low-income, post-conflict countries like Cambodia.[23]

The stigma surrounding particular diseases can further deter people from accessing treatment. In certain cultures this toxic mix of shame and fear can attach itself even to a disease as rife as tuberculosis, which registered some 10 million new cases globally in 2017 with a 3% fatality rate.[24] In Pakistan, for example, 50% of surveyed patients attempted to home-treat tuberculosis, while 42% searched pharmacies for a cure.[25] Anything, rather than brave vital face-to-face treatment at a healthcare center.

Nor should one overlook the gender divide. Many women in developing countries find it harder to seek out (and afford) professional healthcare than their male counterparts. The experience of women in Chad (life expectancy: 54 years) can be illustrative, with research revealing that men overwhelmingly control access to medics, treatments and knowledge. For rural women in particular, this means the progression of an illness is highly dependent on the quality of their support systems (husbands, male family members) and their ability to mobilize them effectively.[26]

With such an array of factors dictating access to healthcare globally, it is clear there is no single pathway to improvement. What, then, are some of the strategies being employed to democratize healthcare access worldwide?

Addressing challenges of healthcare access

Developing markets require urgent action to improve access to healthcare – this much is clear. Emerging markets are estimated by 2050 to account for 80% of the world’s elderly. Vietnam could see the 65+ age group account for 21% of its population by 2050 (currently 7%), while Thailand’s 65+ share could rise to 30% (currently 10%) in the same timeframe. Combine this with soaring population sizes between now and 2050 (India faces a 46% increase, Malaysia 50%, Philippines 65%) and we can almost hear the clock ticking. [27]

Some of the challenges, as outlined above, are cultural in nature and so will need human responses to counter. As such, and using Asian countries as an example, the WHO identified a raft of steps that would bring rapid multi-demographic benefits to healthcare access in developing markets:[28]

- Information campaigns to educate people on the range, availability and costs of healthcare options

- Greater community participation to simplify access to cash, improve transport links, and reduce healthcare costs

- Marketing initiatives around sexual health and contraception to help overcome stigma and unnecessary shame

- Equity funds to reimburse health providers for services given to the eligible poor

- Community loans, at zero or low interest rates, to pay for medical care when most needed

- Government subsidies enabling low-income families to take out health insurance

- Basic health service packages in the community to overcome issues of remoteness

- Integrated outreach services to overcome transport limitations

- Enhanced communication networks ensuring emergency transport is readily available when needed

- Improved management of health services, incorporating supervision, feedback and accountability

- Where beneficial, service contracts for external providers

- Fixed fees to discourage a system of informal payments

Thinking more broadly, there are numerous strategies currently being trialed across the globe that provide possible roadmaps for progress.[29]

Several states in India, for example, are experimenting with so-called ‘hub and spoke’ healthcare models. Major urban hospitals recruit top-tier physicians, while rural clinics provide basic care further afield. The latter can refer patients up the chain of expertise, with the physicians providing assistance using videoconferencing when necessary.

Brazil has launched manufacturing partnerships with major pharmaceutical firms such as Bristol-Myers-Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline, promising set prices and volumes in exchange for knowledge and technology transfers.

In China, the government is planning drastic steps to improve health access over its expansive territory by ramping-up investment in its public healthcare program, targeting an outlay of 7% of GDP in 2020, up from 5.5% in 2010.

The UN, meanwhile, citing wide disparities in how countries have coped with COVID-19[30], has reiterated its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all[31].

The UN, meanwhile, citing wide disparities in how countries have coped with COVID-19[30], has reiterated its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all[31].

One of its key targets is securing universal access to health services globally, including safe and affordable medicines and vaccines.

From a strategy perspective, it is encouraging more efficient healthcare funding, improved sanitation and hygiene, and crucially, increased access to physicians.

Accessing a digital future

At the forefront of this brave new healthcare world are the opportunities offered by digital technology, a potential game-changer that could bring better healthcare to more people than ever before in emerging markets.[32]

Consider the dilemma of Africa, with 11% of the world’s population but 24% of its disease and just 1.3% of its healthcare workers.

How could digital technology help bridge the healthcare gap? One example is in phone and tablet apps that provide endless opportunities for making healthcare both faster and cheaper. The industry calls it mHealth (mobile health) – a technological method of uniting the various stakeholders in the healthcare chain (patients, service providers, payment providers and regulators) under one umbrella.

How could digital technology help bridge the healthcare gap? One example is in phone and tablet apps that provide endless opportunities for making healthcare both faster and cheaper. The industry calls it mHealth (mobile health) – a technological method of uniting the various stakeholders in the healthcare chain (patients, service providers, payment providers and regulators) under one umbrella.

Imagine a near-future scenario where patients can have consultations with specialists, receive appointments with doctors, order medicines, pay for services or seek health advice, even if separated from hospitals and clinics by thousands of miles.

Picture the reality of remote diagnostics for tests, referrals and emergency admissions – all conducted via smartphone.

Picture the reality of remote diagnostics for tests, referrals and emergency admissions – all conducted via smartphone.

Governments, for their part, should need little convincing of the benefits. Such apps can also serve as mobile stock management systems, providing manufacturers and suppliers with live inventories of medicines and equipment. Budgeting and planning instantly become more responsive.

Data gathering can even help with disease surveillance, helping to predict and limit outbreaks (the current coronavirus being a prime example) as and when they materialize. The 2019 Global Health Security (GHS) Index analysis should help focus minds in this regard, highlighting (even before the emergence of COVID-19) countries’ lack of pandemic preparedness. Declaring national health security to be “fundamentally weak around the world”, it calculated an average score for prevention, detection and response of just 40.2 out of 100 across the 195 countries surveyed.[33]

The potential for a digital healthcare revolution doesn’t end there. For countries with vast geographical boundaries, adopting a system of Electronic Health Records (EHR) can accelerate access to healthcare – and deliver a more joined-up service – by radically simplifying the sharing of patient information. Here, newcomers can learn from the missteps of developed markets, such as the USA’s costly (US$ 100 million+) EHR scheme that went live in 2015, or the UK’s ultimately abandoned effort to launch a similar system across its National Health Service (NHS). Newly available cloud technologies allow far more efficient EHR solutions, bypassing the need for so many specialist programmers and datacenters.

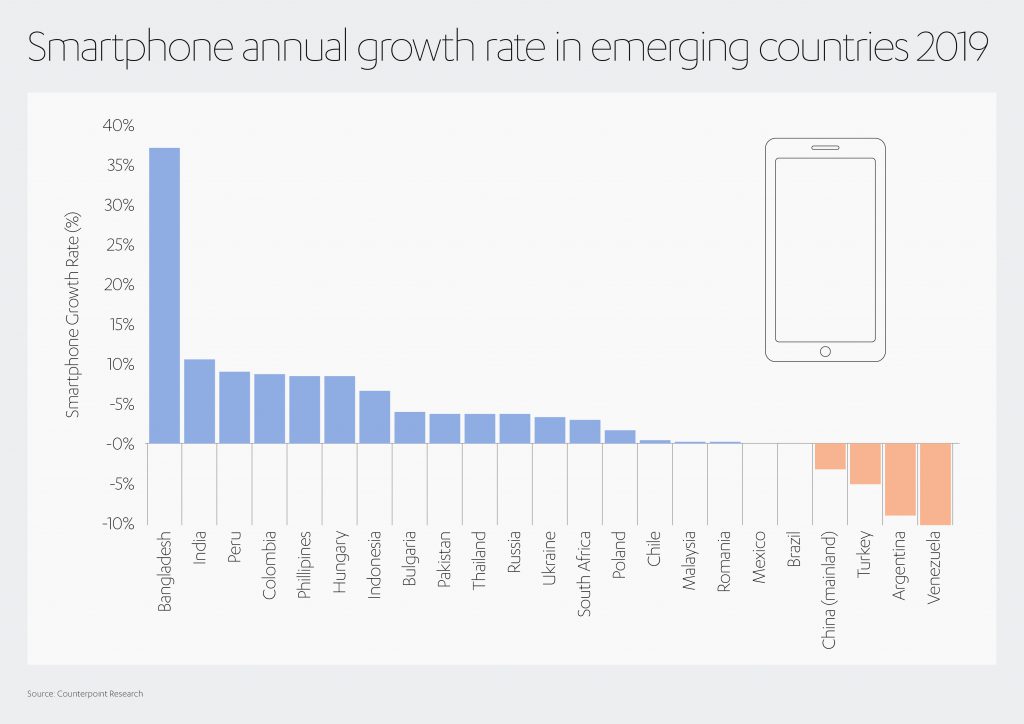

If all this sounds far-fetched for less wealthy countries, take heart from the rise of cell phones even within emerging markets. Bangladesh, for instance, saw its number of smartphones increase by 37% in 2019.[34] While a report from consultants at Deloitte found that by the end of 2018, 97% of Kenyans have access to a smartphone, up from 49% just three years earlier.[35]

The long-imagined transformation in access to healthcare could be just a button-press away…

Healthcare for the many, not just the few

If we are careless or lack imagination, global healthcare inequality can easily be regarded as one of those ‘too big to fix’ problems. And yet, access to high quality, effective healthcare is central to the ‘infrastructure of life’ in which Abdul Latif Jameel is a committed investor. Rather than being intimidated by the challenges, we feel a sense of excitement at the potential breakthroughs that are within reach even now.

Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel said:

“Improving access to healthcare is a complex puzzle that requires a very deep understanding of both needs and solutions. Different countries – even different communities within the same country – will have different needs and different challenges to overcome. It may be technology, infrastructure, distribution, availability, expertise or any number of other hurdles. Adequately addressing these issues has persistently proved to be one of societies biggest challenges. But now more than ever, we have the technology and the expertise to start making real progress. And I’m hugely excited by the opportunities ahead.”

For several years, Abdul Latif Jameel has been helping to make healthcare more accessible and available to those who need it most through its research labs, the Jameel Institute, or J-IDEA (the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics) at Imperial College London; the Jameel Clinic, or J-Clinic (the Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health) at MIT, and J-WAFS (the Abdul Latif Jameel Water & Food Systems Lab), also at MIT.

But while Abdul Latif Jameel is passionate about research and development, it is also acutely aware of the need to transfer innovation, expertise and new technologies out of the labs and into real-world action.

That is why it established the Abdul Latif Jameel Hospital in 1995, the first non-profit rehabilitation hospital in Saudi Arabia, providing comprehensive care for adults and children. It’s also why it is putting so much energy behind its collaborations with Japanese companies Cellspect and Cyberdyne.

With Cellspect, it is helping to provide speedy and affordable blood testing in developing countries across the Middle East, Africa, Southeast Asia and India. The biomechanical finger-pricks currently check sugar metabolism, lipid and liver function – delivering results in just five minutes.

Cyberdyne specializes in pioneering spinal injury rehabilitation technology.

The newly-expanded partnership with Cyberdyne will allow it to roll-out this technology to patients across the Gulf region.

In particular, the Abdul Latif Jameel Hospital will become a regional training hub for Cyberdyne’s Hybrid Assistive Limb (HAL®) technology – one of the World‘s first cyborg-type exoskeleton designed specifically to assist injured people in becoming mobile once more.

Video courtesy of BBC Click & Cyberdyne Inc.[36]

In the COVID-19 era, which has given us a graphic demonstration of the need for dynamic healthcare, it has even more health projects in the pipeline: projects bringing better health to wider areas of the developing World; projects designed to enhance the lives of greater numbers of people; projects, crucially, that will make accessing healthcare a daily reality for those who need it most.

Fady Jameel concluded: “World-leading researchers and healthcare businesses across the globe are constantly pushing forward the boundaries of what is possible, as we seek to make high quality healthcare universally accessible to those that most need it. Our ambition is to get these ideas, innovations, products and solutions out of the labs and the research centers and into the communities who need them. It is a challenge that cannot be underestimated, but in which we must succeed.”

[1] The World Social Report 2020, published by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), shows that income inequality has increased in most developed countries, and some middle-income countries – including China, which has the world’s fastest growing economy.

[2] https://www.who.int/data/gho/whs-2020-visual-summary

[3] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/324835/9789241565707-eng.pdf

[5] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)30818-8/fulltext

[6] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/324835/9789241565707-eng.pdf

[7] https://www.who.int/countries/ssd/en/

[8] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(17)30488-6/fulltext

[9] https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1_ch13#

[10] https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/alliancehpsr_jacobs_ir_barriershealth2011.pdf

[11] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)67599-X/fulltext?code=lancet-site

[12] https://www.who.int/hdp/en/

[13] ‘Modeling the effects of health on economic growth’ Journal of Health Economics, Volume 20, issue 3

[14] https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/529000

[15] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/09/19/decline-of-global-extreme-poverty-continues-but-has-slowed-world-bank

[16] https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/impact-covid-19-coronavirus-global-poverty-why-sub-saharan-africa-might-be-region-hardest

[17] https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-with-universal-healthcare

[18] https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-7-262

[19] https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/alliancehpsr_jacobs_ir_barriershealth2011.pdf

[20] https://www.education-inequalities.org/

[21] https://www.who.int/data/gho/whs-2020-visual-summary

[22] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12477744/

[23] https://www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/trust-in-the-context-of-community-based-health-insurance-schemes-in-cambodia-villagers-trust-in-health-insurers

[24] https://www.who.int/gho/tb/epidemic/cases_deaths/en/

[25] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/116501/dsa710.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[26] http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3743/1/3743.pdf?DDD5+dan0krh+dan0rab+dul4ks

[27] https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/high-growth-markets/assets/the-digital-healthcare-leap.pdf

[28] https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/alliancehpsr_jacobs_ir_barriershealth2011.pdf

[29] https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/magazine/mso-healthcare-in-emerging-markets.html

[30] https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/news-centre/news/2020/COVID19_UNDP_data_dashboards_reveal_disparities_among_countries_to_cope_and_recover.html

[32] https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/high-growth-markets/assets/the-digital-healthcare-leap.pdf

[33] https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf

[34] https://www.counterpointresearch.com/smartphone-growth-emerging-markets-will-continue-2019/

[35] https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ke/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/Deloitte_GMCS_Report_The_Kenyan_Cut_August_2019.pdf

[36] https://www.cyberdyne.jp/english/company/Media_detail.html?id=7444

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit