J-WAFS in action: Farm waste to fertilizer – improving soil quality in agricultural communities

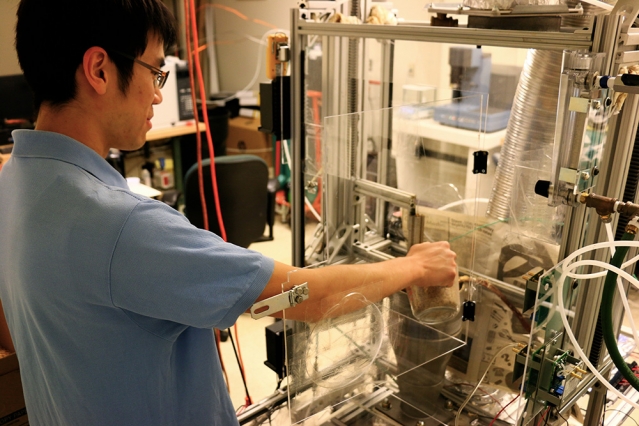

Ahmed Ghoniem, Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT (above), and Kevin Kung, a PhD student in the School of Engineering, are leading one of the latest MIT research projects awarded J-WAFS funding earlier this year. Ahmed and Kevin are looking to refine new biomass processing technology to produce fertilizer on a small scale in rural communities, using mostly local resources, labor and agricultural waste.

Opening Doors spoke to Ahmed (AG) and Kevin (KK) about the project and its aims.

What is the title of your research project?

AG: The project is called “Decentralized torrefaction for producing high-yield, irrigation-saving fertilizer.”

What issue are you seeking to address?

KK: Many smallholder farmers in rural communities, particularly in developing countries, depend on costly, synthetic fertilizers imported from abroad. The misuse of these fertilizers – using the wrong fertilizer in the wrong context – can often lead to soil acidification and crop yield loss.

For example, I was working in Kenya in 2013, and I noticed that a lot of smallholder farmers would indiscriminately use one type or other of chemical fertilizer, without consideration for the specific nature of the soil. In some cases, it led to an improvement in yield, but in other cases it had the opposite effect. Many farmers had noticed that their soil was degraded, but they weren’t sure why.

Part of the problem was knowledge, in that they weren’t aware of the correct fertilizer for their context, but it is also about access. Imported fertilizer tends to be quite expensive, so farmers can often only afford the cheapest variety. They don’t have five or 10 different types to choose from, according to their soil type.

In simple terms, can you briefly describe your proposed solution?

KK: The general concept of burning organic waste to produce fertilizer is not new. For thousands of years, people would burn wood and plant matter and then mix the resulting ‘char’ in the soil to fertilize it.

The technology to scale up and commercialize this so-called ‘torrefaction’ process is not new either. But it is a very large-scale process, producing hundreds of tons a day, and the equipment costs millions of dollars.

Our objective is to design something that brings the torrefaction process to the local level, so it can work in rural settings, using locally available resources and labor, to cost-effectively produce fertilizer on a village or community scale.

AG: There is also a second objective, which is to develop a ‘clean’ method of biomass torrefaction that doesn’t release harmful compounds, like soot, into the environment. So although the concept of biomass torrefaction is not new, we are trying to make it more environmentally-acceptable at a scale where it is both economically viable and accessible to farmers.

Could you explain the torrefaction process?

KK: Torrefaction is a thermo-chemical process. You start with biomass, such as old crops or agricultural waste and you heat it up. The heat causes chemical reactions in the matter and you lose a lot of the ‘bad’ stuff, like acids and CO2.

What’s left is something that is more carbon rich, called ‘torrefied biomass’, or ‘biochar’. This is alkaline, so in acidic soil it acts as a liming agent and restores a lot of the nutrients and the pH balance to the soil.

Produced under the right conditions, it also has a porous structure that allows it to retain nutrients and moisture more effectively, which can help to improve the condition of bleached soil.

Is your technology aimed at individual farmers, or at the village and community level?

KK: Typically, we expect it to be aimed at a village level, so maybe a 10-20km radius with about 500 to 1,000 farmers. It’s much easier to coordinate it at a village level where you have a harvest season and it is very intensive.

AG: This is actually one of the issues we’re still working in. Our concept is based on a mobile torrefaction system that can move from community to community on the back or a trailer or similar. Optimizing the process clearly means we need to find the right size farm or village where that torrefaction reactor can park up and perform the process, and leave the charcoal behind to be used on the farm, or distributed locally. There may even be surplus product that could be sold to earn additional income.

Are you confident that the product can be delivered at a low enough cost to be commercially viable in those communities that most need it?

KK: This is one of the areas we are looking to refine over the next 12 months, to demonstrate that this will work.

The basic technology is already in place and we have demonstrated that it will work in the lab. The next task is to scale it up and make sure it still works in the environments we are focusing on, or if we need to make any interventions. And then how do we translate that into a design that uses local components as much as possible.

AG: The local manufacturing element is important. We want to explore the local talent and capabilities in these areas, so that most of the equipment can be produced and assembled locally, keeping costs to a minimum.

How important is this funding from J-WAFS Solutions in terms of helping you achieve these ambitions?

AG: It is vital. Most of our previous work on biomass torrefaction has been focused on turning biomass into energy, rather than fertilizer. So the whole area of agriculture and food production is relatively new to us.

The funding from J-WAFS Solutions is enabling us to take the essential first steps to start making in-roads into this market, and hopefully turning our vision into a reality.

We are confident, too, that working with J-WAFS can help us not only in terms of the technology development, but also in exploring diversification and the commercialization of the technology.

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit