Oceans of opportunity: managing our most prized resource

It is commonly understood that water is essential to life. So, with water set to become more precious than oil, just why are we so bad at managing this most prized of resources?

The data shows that by 2030, almost half the global population will suffer from water stress, and demand will outstrip supply by 40%[1] if we don’t change current consumption patterns. Alarmingly, 2030 is already less than a decade away. The need to act is getting more urgent every year.

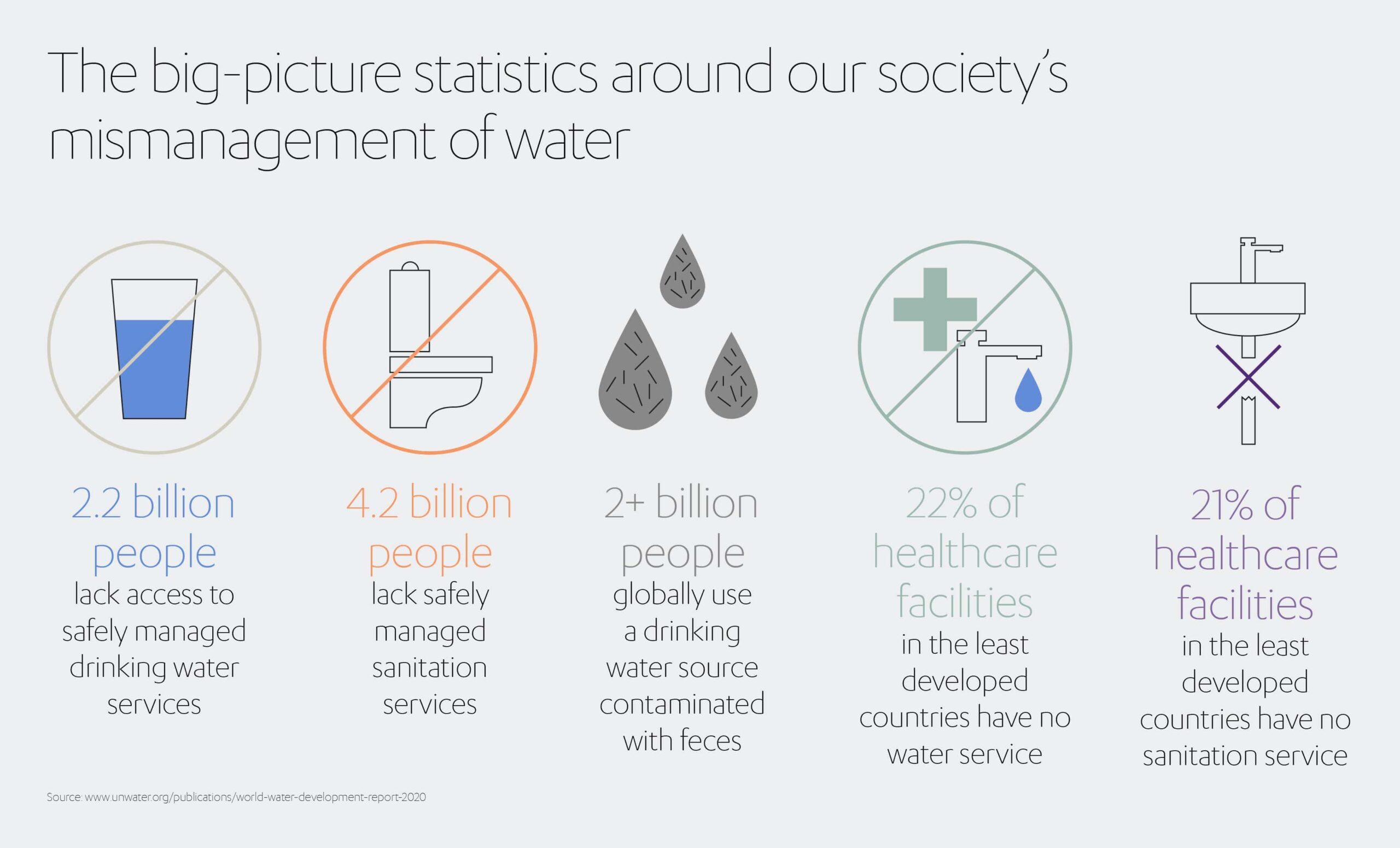

The big-picture statistics around our society’s mismanagement of water should do more than raise eyebrows.

So, how do we galvanize governments, businesses, and individuals to act?

With almost three-quarters of our planet covered by water, increasing our supply sounds like it should be easy. Unfortunately, however, only 1% of that water is fit for human consumption. The rest is either frozen, or out of reach in oceans, lakes and groundwater.

“It is ironic that in our world of vast water resources, only a tiny fraction is available to support life, while huge numbers of inhabitants lack enough water to live on, often due to our own mismanagement of resources,” said Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel

Addressing the problem of water scarcity is not only a question of providing water to drink, to support our communities and to keep the wheels of industry turning. As Fady Jameel explains in his Spotlight article on water scarcity, the impact of water availability extends far into other issues that are central to the wellbeing, success and sustainability of human civilization itself.

Take hygiene. As the global pandemic so tragically demonstrated, poor hygiene increases the risks of spreading preventable diseases. Currently, around one-third of people worldwide do not have access to safe drinking water and over 50% lack access to safe sanitation[6]. If everyone did, it is estimated that the global disease burden would be reduced by 10%. Furthermore, over 4.2 billion people – around half the population of our planet – lack safe sanitation and two-out-of-five people do not have access to basic hand-washing facilities at home[7]. This has a devastating impact on child mortality, with around 300,000 children under five dying every year from diarrheal diseases due to poor hygiene or unsafe drinking water[8].

Agriculture – one of the biggest water consumers – is another critical area where a consistent supply of suitable water is essential. Without enough water, our ability to feed our communities is jeopardized and food security is weakened. With the global population expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050[9], demand for water is only heading in one direction and the issue of food security will grow significantly. Increasing agricultural production has also been shown to be one of the most effective ways to reduce poverty,[10] so ensuring we have adequate water supply can not only strengthen food security, it can also help to reduce global poverty, two of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

There are indirect benefits, too. Improving the supply of water to towns and cities; to industries; to farmers and rural communities; can help to reduce the risks of conflict. Water insecurity can be a catalyst of disputes between people, communities and even states. While conflict itself often has a devastating impact on water supplies[11].

Reducing water scarcity can also help to create fairer, more equal societies. Women and girls are disproportionately affected by the lack of access to basic water, sanitation and hygiene facilities. When water is not available, four times out of five it is women and girls who are responsible for collecting it. This can greatly reduce the amount of time they have for school or work. Women who collect water also carry a greater amount of unpaid domestic work, leaving less time to do work that generates income[12].

The problems around water scarcity do not only affect those regions typically regarded as under-supplied with water, such as parts of Africa or the Middle East. It affects every region. In Latin America, for example, as discussed in our Abdul Latif Jameel Perspectives article on the water challenges facing Latin America, around 36 million people lack access to drinking water[13] and 100 million lack access to sanitation. Factor in those reliant on latrines or septic tanks and that figure rises to 256 million.[14]

Fortunately, we do not have to wait until a solution to these problems is discovered. We already have at least some of the answers to this puzzle at our fingertips.

Re-use and recycle

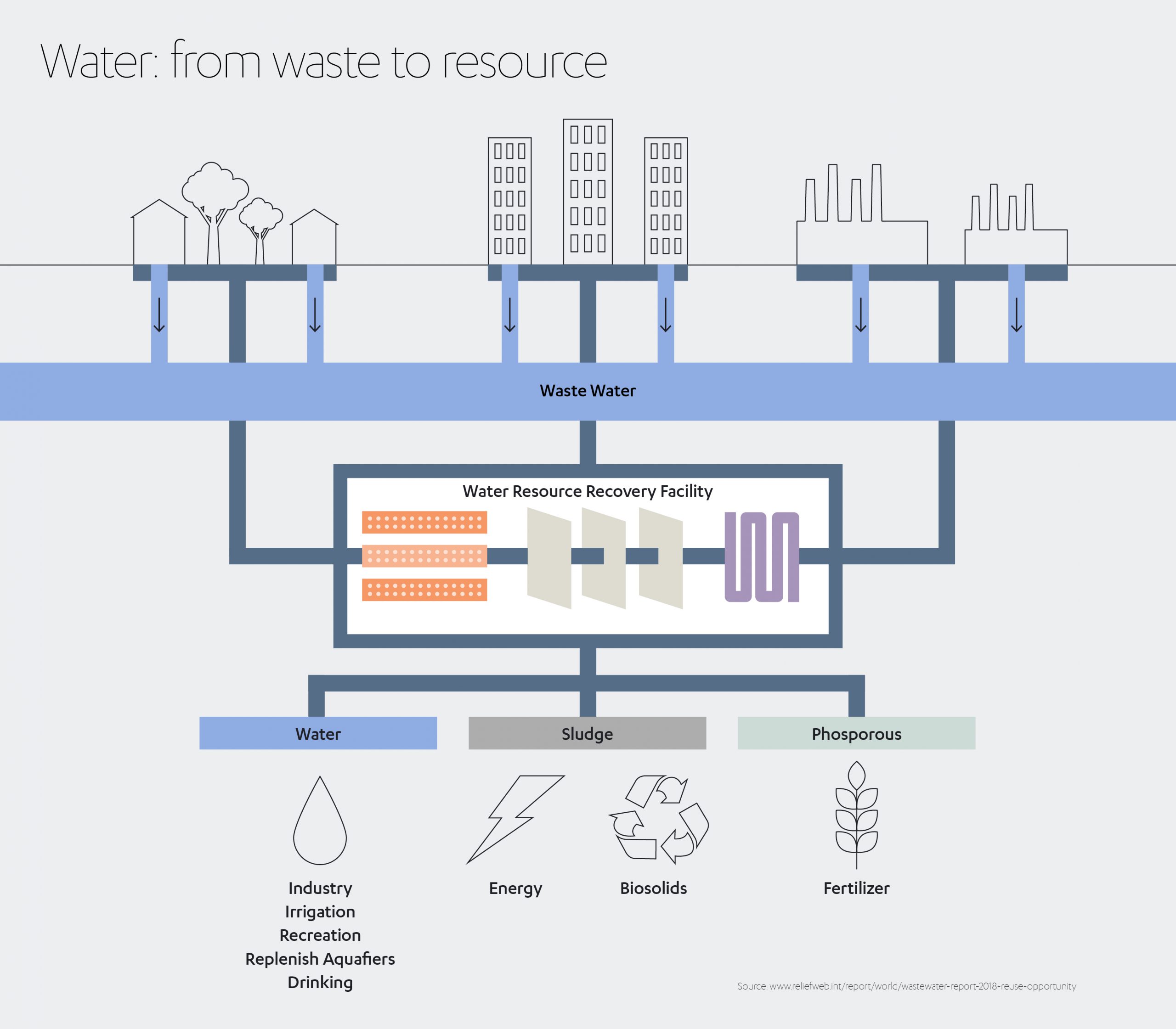

There are two main ways to improve the global availability of fresh water: either to use our existing supplies more efficiently, by reducing, re-using and recycling wastewater (read our Abdul Latif Jameel Perspectives article on growing investment in wastewater treatment systems); or to increase the existing supply through seawater desalination (Fady Jameel’s Spotlight article discusses advances in water desalination technology).

Wastewater, as the name suggests, is water that has already been used in our homes, businesses and industries, and is then released back into the environment. Currently, around 80% of wastewater is discharged without adequate treatment. By improving the treatment of wastewater, removing the pollutants and contaminants, it can be recycled back into our water systems and re-used, whether in industry, agriculture or as drinking water.

Simple in theory. But investment in wastewater treatment systems to date has been limited, due to a combination of public skepticism, regulatory barriers, poor economic incentives and lack of government support.

There are signs that this is changing, however, thanks largely to growing urgency around the climate emergency, and a change in approach on behalf of authorities. According to the International Water Association, the global market for wastewater recycling and reuse is estimated to reach US$ 22.3 billion by 2021, almost double what it was five years previously[15].

The European Union is a case in point. Wastewater treatment policy was, until very recently, fragmented along national lines. But in 2020, a new Water Reuse Regulation was approved which defines EU-wide minimum requirements for reclaimed water to be used in agriculture. The new regulation has the potential to increase the bloc’s water reuse to 6.6 billion cubic metres per year, from the current 1.1 billion[16].

Carlos Cosín, CEO of global water infrastructure development company Almar Water Solutions, part of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy, welcomes the EU’s action, but says that to truly capitalize on the potential of wastewater treatment to ease our water challenges, a similar framework is needed at an international level.

“A global framework is needed like the approach being taken in the EU. Currently, each region and country is working towards its own regulation, rather than adopting a more unified approach. This will be the biggest challenge over the next 10 years,” he says.

There are positive examples across the globe that demonstrate the potential of wastewater to transform the efficiency of our water use. The city of Aqaba in Jordan, for example, one of the world’s most water-scarce countries, collects and treats 90% of its wastewater – around 31,000 million m3/day. Singapore, meanwhile, uses a process of microfiltration, reverse osmosis, ultraviolet disinfection and alkaline pH balancing, to supply 40% of the city-state’s water needs.

A salty solution

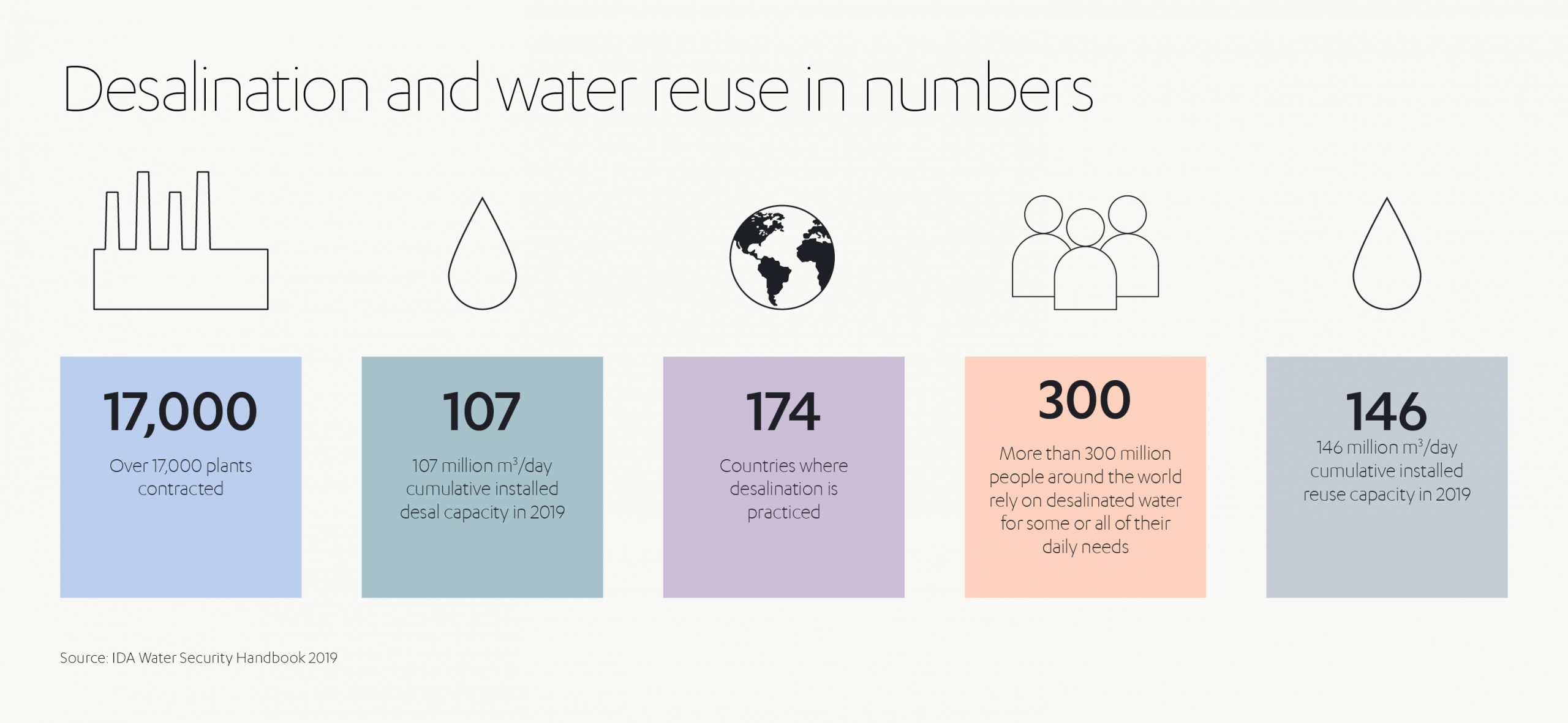

Increasing the (re)use of wastewater clearly has enormous potential to help address the problem of global water scarcity. The other main tool is water desalination.

Water desalination is the process of extracting dissolved salts from seawater to create fresh water. This can be converted into ultrapure water for drinking, or potable water for industry and agriculture. The two main desalination technologies are thermal desalination, which uses heat to evaporate water and separate it from the salt, and membrane desalination, which uses reverse osmosis to transfer water through semi-permeable membranes to remove salt and other impurities.

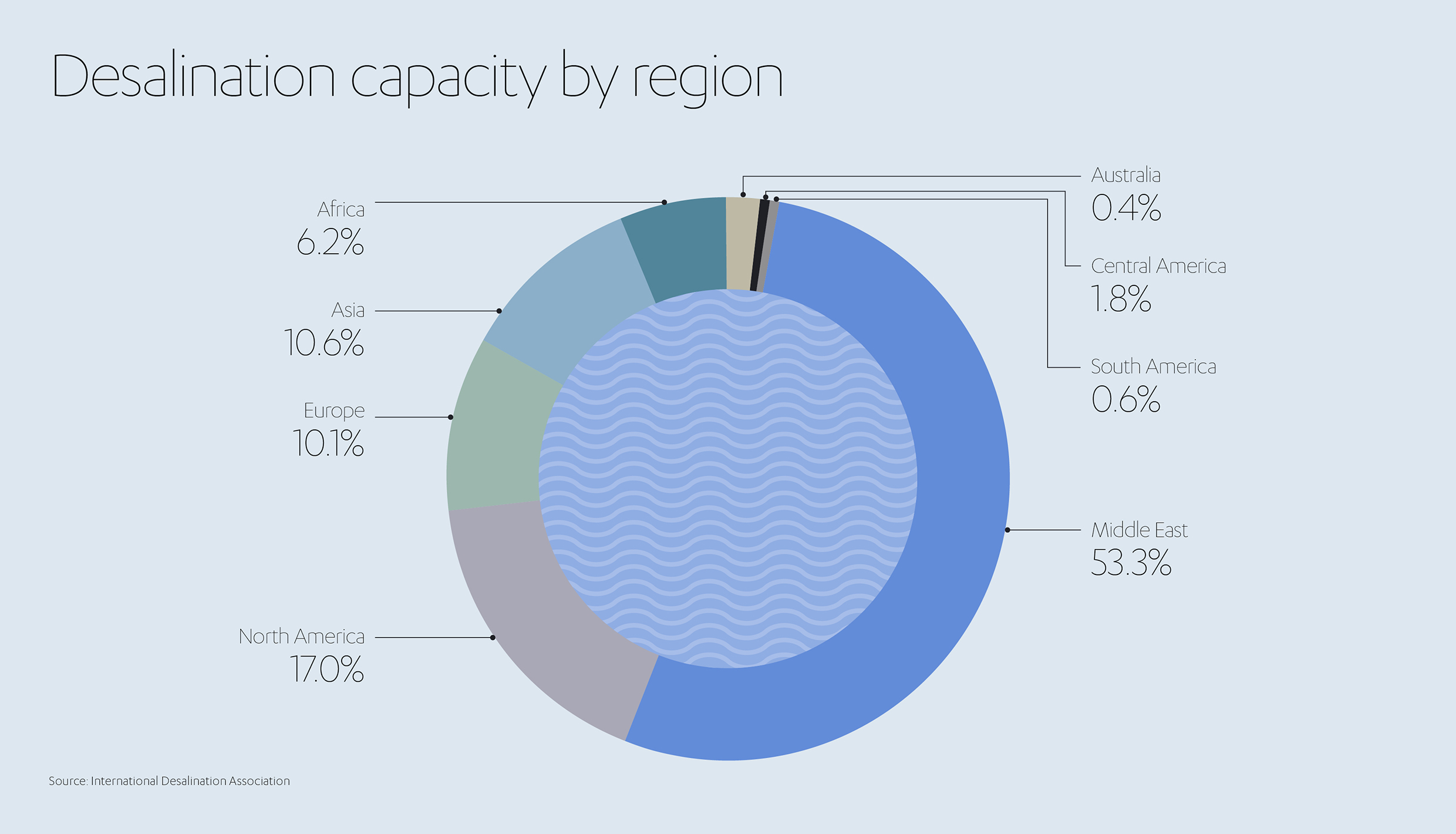

There are already over 17,000 desalination plants across the globe[17]. The Middle East accounts for just under half of total capacity, while Asia, China and the United States are rapidly increasing their desalination capacity, as are several countries in Latin America.

One of those countries leading the charge in Latin America is Chile, where Almar Water Solutions acquired water treatment company Osmoflo SpA. Since the acquisition, it has already expanded its client portfolio, winning a three-year water services contract for mining company Mantos Copper.

“We intend to use this experience in Chile as a springboard for other Latin American projects. It supplements our portfolio of desalination, drinking water treatment, wastewater purification and industrial water operations, demonstrates our ambitious plans for the future,” says Carlos Cosín.

The development of the desalination industry has historically been hampered by high costs, not only financially, but also environmentally, as desalination plants require huge amounts of energy to operate – energy that is usually derived from fossil fuel sources.

Recent advances, however, could boost the development of renewable-energy-powered desalination plants that can help to reduce water scarcity more efficiently and more sustainably. These innovations are explored in more detail in our Perspectives article on renewable desalination.

“Renewable energy is the future of desalination in my opinion. It’s only a matter of time in the Middle East region. In less than five years, battery storage technology will have developed to the extent it will be possible to have an independent solar and photovoltaic desalination plant,” says Carlos Cosín.

Committed to a more sustainable future

Almar Water Solutions itself is enabling Abdul Latif Jameel to play an increasingly significant role in addressing global water scarcity challenges.

As well as its operations in Chile, the company has a major stake in the Muharraq wastewater treatment plant in Bahrain, and in 2018 it was awarded the contract to develop Kenya’s first large-scale desalination plant in Mombasa, the country’s second largest city, to supply drinking water to more than one million people.

In January 2019, Almar Water Solutions was awarded the contract to develop Shuqaiq 3 IWP in Al Shuqaiq, on the Red Sea cost of Saudi Arabia – one of the world’s largest desalination plants – with the capacity to deliver clean water to around 1.8 million people every day. Later the same year, it entered into a joint venture in Egypt with Hassan Allam Utilities to help revitalize the country’s water infrastructure. This led to the acquisition of Ridgewood Group, Egypt, a major desalination services company, which operates 58 desalination plants across the country.

The rapid expansion of Almar’s portfolio of water infrastructure assets is a sign of the intent and commitment of Abdul Latif Jameel to tackling this most pressing of challenges, and to improving access to sustainable water supplies for communities across the globe.

Only by prioritizing the water challenge and encouraging investment, innovation, and partnerships across society, can we develop the solutions required to strengthen water security and ensure access to water for all those who need it.

[1] https://www.unwater.org/publications/world-water-development-report-2020/

[2] Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UN-Water

[3] Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UN-Water

[6] Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UN-Water

[7] Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UN-Water

[9] https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2019.html

[10] The state of food insecurity in the world – 2012 (fao.org)

[11] Water is a growing source of global conflict. Here’s what we need to do | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

[12] WHO | Water, sanitation, and hygiene: measuring gender equality and empowerment

[13] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/03/20/america-latina-tener-abundantes-fuentes-de-agua-no-es-suficiente-para-calmar-su-sed

[14] https://www.worldwatercouncil.org/fileadmin/wwc/News/WWC_News/water_problems_22.03.04.pdf

[15] https://reliefweb.int/report/world/wastewater-report-2018-reuse-opportunity

[16] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/04/07/water-reuse-for-agricultural-irrigation-council-adopts-new-rules/

[17] https://idadesal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/World-Bank-Report-2019.pdf

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit