Bold IDEA to combat the rise of infectious diseases

Sometimes, a tragedy is too vast in scope to be ignored. The number of lives claimed by infectious diseases is one such tragedy, and it’s unfolding year after year before our very eyes.

By Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel.

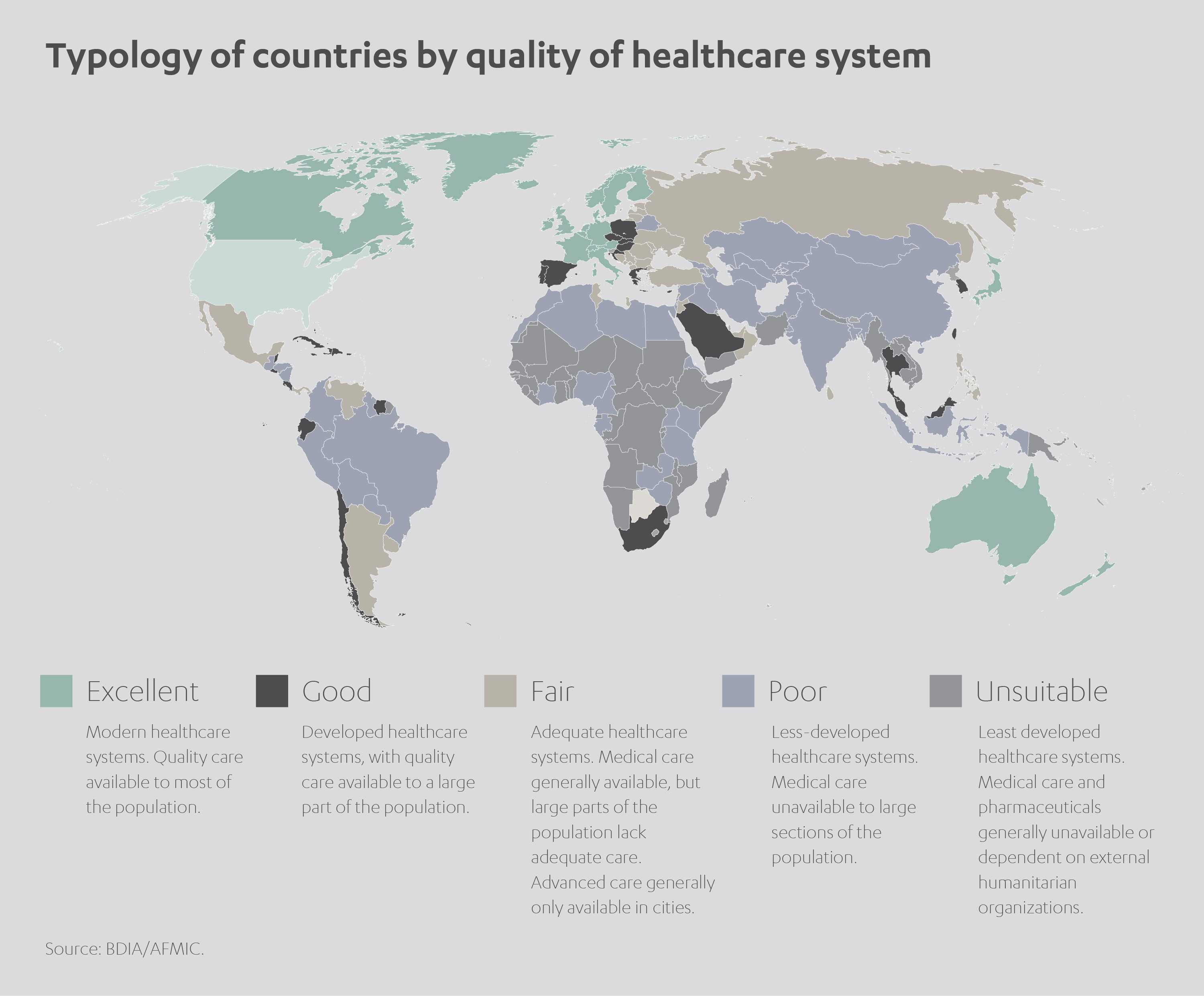

The moral imperative is particularly acute because the countries most severely affected by infectious diseases – poorer, so-called Third World countries – are often those lacking the resources to respond with appropriate urgency.

It doesn’t have to be like this. I believe modern technology and data intelligence have given us the potential to tackle this global catastrophe with unprecedented precision. Our challenge is therefore clear: how to use the new tools at our disposal to fight back against this growing menace and start saving more lives.

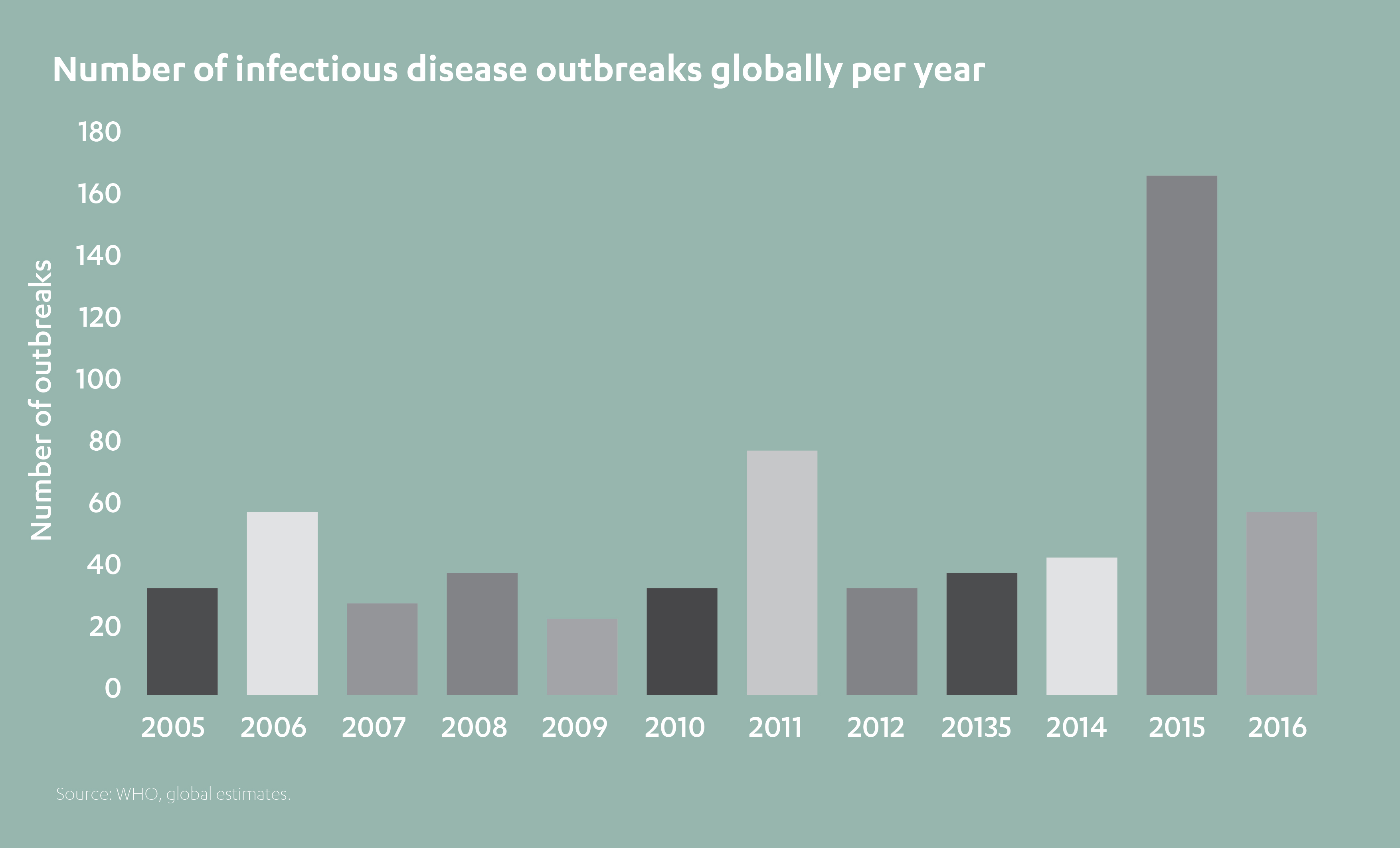

Wherever you look, the figures make alarming reading.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), infectious diseases kill almost nine million people annually, many of them children under five. Among those fortunate enough to survive, many more face lifelong disabilities.[1]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), infectious diseases kill almost nine million people annually, many of them children under five. Among those fortunate enough to survive, many more face lifelong disabilities.[1]

Communicable diseases feature heavily among the top ten causes of death worldwide. Lower respiratory infections (typically pneumonia) caused some three million deaths in 2016; diarrhea around 1.4 million deaths; tuberculosis, 1.3 million deaths; and AIDS a further one million.[2]

And yet, this is only a glimpse of the true calamity, as media headlines attest to renewed outbreaks of Ebola, cholera, the Zika virus and MERS, adding countless more fatalities to the global tally.

Charting a trail of destruction

The rapidly evolving science of epidemiology helps us track where new disease outbreaks occur and how quickly they spread. It also allows us to gauge when an epidemic (a sudden spike in cases of a certain disease within a population) evolves into a pandemic (one spread across several countries or even continents).

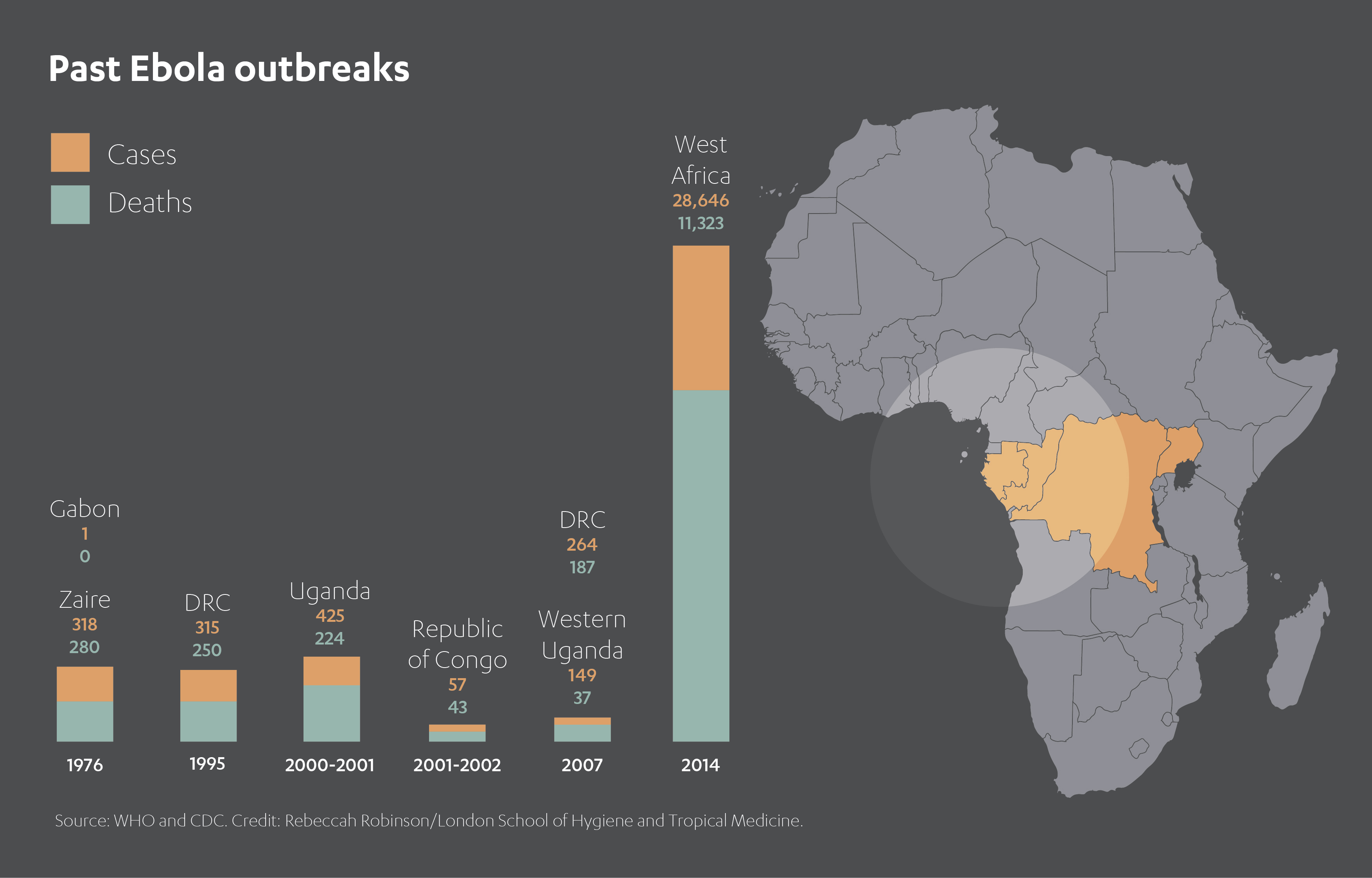

For instance, the WHO describes the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, which started in Guinea and then spread across Sierra Leone and Liberia, as the worst pandemic since the virus was first discovered in 1976. Guinea experienced more than 2,500 deaths, Sierra Leone almost 4,000, and Liberia close to 5,000. Currently, the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo is in the grip of its own outbreak.[3]

The specter of cholera is rarely far away, with recent outbreaks in Angola, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Vietnam, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa. A single epidemic in Zimbabwe in 2008, lasted almost a year and spread throughout the country as well as to neighboring Zambia and South Africa. Yemen’s cholera outbreak of 2016 was described by the WHO as “the worst cholera outbreak in the world”. Global cholera infections are estimated anywhere from three to five million annually, accounting for 100,000 to 130,000 deaths.[4]

Although only recently gaining global attention, the Zika virus was first identified in Africa and Asia in the 1950s. It wasn’t until 2013 that it entered the Oceania region, but subsequently lost little time in infiltrating the Americas. A 2015 outbreak originating in Brazil quickly spread to other countries in South America as well as Central America, North America and the Caribbean. Some 1.5 million cases of Zika were recorded in Brazil alone. An especially cruel virus, it can be transmitted from pregnant women to their unborn children, often resulting in the life-limiting condition known as microcephaly.

Indeed, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDPC) reported around 1,500 cases of microcephaly in Brazil following the 2015-2016 outbreak.[5]

Indeed, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDPC) reported around 1,500 cases of microcephaly in Brazil following the 2015-2016 outbreak.[5]

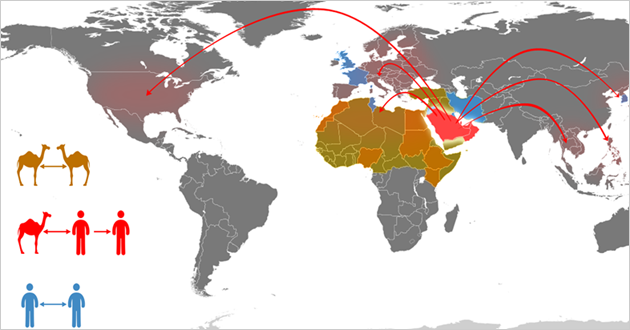

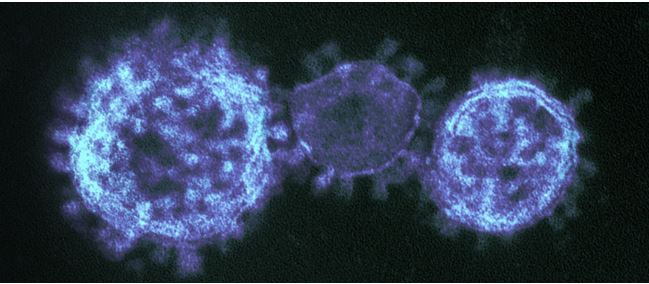

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), the respiratory infection otherwise known as ‘camel flu’, is another growing danger which demands our extreme vigilance.

Initially emerging in Saudi Arabia in 2012, and spreading around the Arabian Peninsula, MERS claims a fatality rate of more than one third.

Demonstrating an unnerving ability to cross continents, one MERS strain was identified in a patient in London in 2012. This was followed three years later by a large outbreak in South Korea. Some 6,508 people were quarantined during this flare-up, which led to 184 confirmed cases and 19 deaths. [6]

Perfect storm exposes our vulnerability

The world in which we live today is starkly different to the world of several decades ago. A booming population is placing new strains on infrastructures and resources. In many countries, greater numbers of people are living in closer confines than ever before.

Climate change is increasing the rate of natural disasters such as floods and hurricanes, which devastate living conditions and condemn many to an unsanitary environment. Wars and border conflicts, their manmade equivalent, have a similar impact.

Concurrently, there has been an exponential increase in global mobility, meaning localized epidemics now have worldwide reach. This ‘perfect storm’ lends fresh urgency to efforts to combat the emergence and spread of these calamitous – and often preventable – infectious diseases.

A report by the NCBI for the National Institute of Health in the United States, for instance, tracks disease outbreaks in the aftermath of natural disasters.[7]

A report by the NCBI for the National Institute of Health in the United States, for instance, tracks disease outbreaks in the aftermath of natural disasters.[7]

It recorded an outbreak of diarrheal disease after the Bangladesh floods of 2004 involving more than 17,000 cases; and more than 16,000 instances of cholera following flooding in West Bengal in 1998.

The eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991 led to around 18,000 cases of measles among the densely packed displaced population. Pakistan registered more than 400 measles patients after the 2005 South East Asia earthquake. A sharp rise in malaria cases in Costa Rica in 1991 was linked to an earthquake in the country’s Atlantic Region in 1991.

Taking another perspective, a report in respected medical journal The Lancet in 2002 examined the impact of diseases arising during and after the ultimate manmade disaster – war.

It identified 25 conflict-hit countries, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where respiratory infections, diarrhea, measles and malaria comprised 70% of all deaths.

It estimated that ‘crude mortality rates’ were more than 60 times higher than baseline rates after mass displacements and highlighted the 12,000 Rwandan refugees killed in June 1994 following the outbreak of cholera and dysentery in Goma.[8]

The picture might be bleak, the pattern clear. And yet all is not lost. As the peril grows, so too does our means of response. And it is here that I’m determined Abdul Latif Jameel can make a significant difference.

Technological solutions to natural problems

Artificial intelligence (AI) is establishing itself as our most valuable weapon in the fight against infectious diseases. Using advanced computer systems, we’re increasingly able to decipher their previously unpredictable appearance and spread.

At its most fundamental level, AI enables us to gather live data as new outbreaks of infectious diseases occur, and predict their likely behavior by mapping this data against existing models. This, in turn, helps emergency teams and scientists devise the most rapid and effective strategies to contain the threat – potentially, even preventing outbreaks before they have time to take root.

Delving deeper, the areas in which AI can bolster our defenses against infectious diseases are almost limitless. Consider the value of real-time analysis and modeling to contain outbreaks; improving on-site data collection and unlocking its hidden clues; identifying more reliable methods for safeguarding displaced civilians; better understanding susceptibility and resilience factors; strengthening health systems in disease hotspots; and accelerating access to urgent treatments.

We’re still barely scratching the surface, and yet these benefits stretch beyond the merely hypothetical – the technology is with us now and is already beginning to make an impact around the world.

If AI resides in a state of relative infancy, our challenge becomes bringing it to maturity and maximizing its potential for changing lives for the better.

Funding a revolutionary new IDEA

Encouragingly, while the challenge appears huge, so too is our ability to make a game-changing difference. With AI’s potential to save tens of thousands of lives per year, and maybe millions in the longer term, the onus is on us to act.

And that’s why Community Jameel is proud to be partnering with Imperial College London to establish the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics, or J-IDEA.

J-IDEA is a rapid response research center to predict and prevent global health crises.

Governments around the world are investing in better health – but with budgets constrained, it is critical that resources are used in the most effective way. By bringing together the world’s foremost epidemiologists, biostatisticians and data statisticians with medics, policymakers and aid workers, J-IDEA will accelerate the development of effective and affordable health programmes, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Data analysis from J-IDEA will provide the evidence that governments and international organisations need to target health interventions – and limited healthcare budgets – for the maximum impact.

The expertise of Imperial College in this area is simply unrivalled.

With work spanning a range of disease areas (emerging infectious diseases, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, polio, influenza, neglected tropical diseases and more), its research teams take a whole-picture approach, with a remit spanning the transmission, evolution and control of infectious diseases across both human and animal populations. Combining epidemiological and genetic analysis with mathematical modeling, field and experimental research, Imperial College has established itself as a go-to resource for policymakers in this field.

Its two existing research centers are the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis – which works with national and international agencies on policy and response for infectious diseases – and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Modelling Methodology – which develops groundbreaking analytical and computational tools to improve public health.

This impressive track record makes Imperial College a natural host for J-IDEA, envisaged as a hub for leading data scientists, medics, epidemiologists, biostatisticians and aid workers.

J-IDEA was borne of a desire to improve the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people. We’ll do this by using data analytics and modeling to explore the causes of global health and humanitarian crises, and then finding radical new solutions for governments, institutions and communities.

In the Middle East, for example, where MERS-coronavirus is endangering life, our team is using modeling methodology to understand how the virus manifests in camels. In doing so, we’re computing both the human risk and the potency of new vaccines. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, meanwhile, J-IDEA is aiding a global effort to stem the escalating tide of Ebola – already making a tangible difference to those areas worst hit.

We’re proud to have epidemiologist Professor Neil Ferguson as our first director, renowned for mathematically modeling the spread of pathogens such as MERS, pandemic flu, Ebola, Zika and SARS. Professor Ferguson is backed by an esteemed team including Professor Majid Ezzati (an expert in global environmental health), Dr. Katharina Hauck (a world-leading specialist in the economics of infectious diseases), and Professor Tim Hallett (an authority on epidemiology and HIV).

We’re proud to have epidemiologist Professor Neil Ferguson as our first director, renowned for mathematically modeling the spread of pathogens such as MERS, pandemic flu, Ebola, Zika and SARS. Professor Ferguson is backed by an esteemed team including Professor Majid Ezzati (an expert in global environmental health), Dr. Katharina Hauck (a world-leading specialist in the economics of infectious diseases), and Professor Tim Hallett (an authority on epidemiology and HIV).

Together, it’s our intention to champion the power of health data analytics, transforming lives locally and across the world.

Joined-up approach to bettering global health

All this, of course, is only part of the wider story. J-IDEA is intended to compliment the work of Community Jameel’s other global health collaboration, J-Clinic.

Launched last year in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), J-Clinic focuses on exploiting AI to prevent, detect and treat debilitating non-infectious conditions such as cancer, sepsis, dementia and other neurological disorders.

Its mission encompasses three core areas: devising new medicines to stop non-infectious diseases in their tracks; creating new diagnostic tests to detect health problems and hasten their treatment; and researching cutting-edge drugs based around personalized therapies.

The team at MIT has made a flying start, already developing a new machine-learning approach to strengthening the ability of antibiotics to kill bacteria. It’s also been busy creating a new predictive model assisting doctors in the treatment of sepsis in hospitals. Another strand of research has focused on designing a new system to identify potential drug candidates in large-scale pharmacological datasets.

It’s clear that, until now, the world hasn’t done enough to combat the proliferation of infectious diseases. Too often we have stood by and let the most vulnerable pay the ultimate price, when we should have been uniting to counteract the threat together.

In tandem with J-Clinic, J-IDEA is the latest critical step in this direction. I’m personally eager to discover what the finest minds can accomplish when equipped with such ambitious investment.

[1] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44850/9789241564489_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2DCF58B1F3B535626C6C4E9C395F42EF?sequence=1

[2] https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

[3] https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease

[4] https://www.who.int/wer/2010/wer8513.pdf

[5] https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/recent-scientific-findings-association-between-zika-virus-infection-and-microcephaly

[6] https://www.independent.ie/world-news/fifth-mers-death-in-south-korea-31284293.html

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2725828/

[8] https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(02)11807-1.pdf

Added to press kit

Added to press kit