Fighting food waste

With the geopolitical conflicts such as that in the Ukraine thrusting world food supplies back on the news agenda, the glare of publicity has returned to one of the most pressing and insidious problems of our time: global hunger.

The figures, when one starts examining the scale of the issue, are a wake-up call for both heart and mind. Around 10% of the world’s population suffers from inadequate nutrition – that’s some 800 million people[1]. Approximately 48 million of these people face acute hunger, with accompanying risks of starvation and death.

Hunger is unfortunately an accelerating crisis too, with 193 million people across 53 countries facing food insecurity in 2021, up nearly 40 million from the previous year. The young are especially vulnerable, with 20% of deaths among under-5s due to malnutrition. Hunger is also one of the world’s most vivid manifestations of inequality, with almost three-quarters of people in food crisis living within just 10 countries: Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia and Nigeria.

As one might expect, one of the biggest causes of acute hunger is a combination of harsh climates and underdeveloped and inefficient local agricultural capabilities relative to the population, and population growth itself.

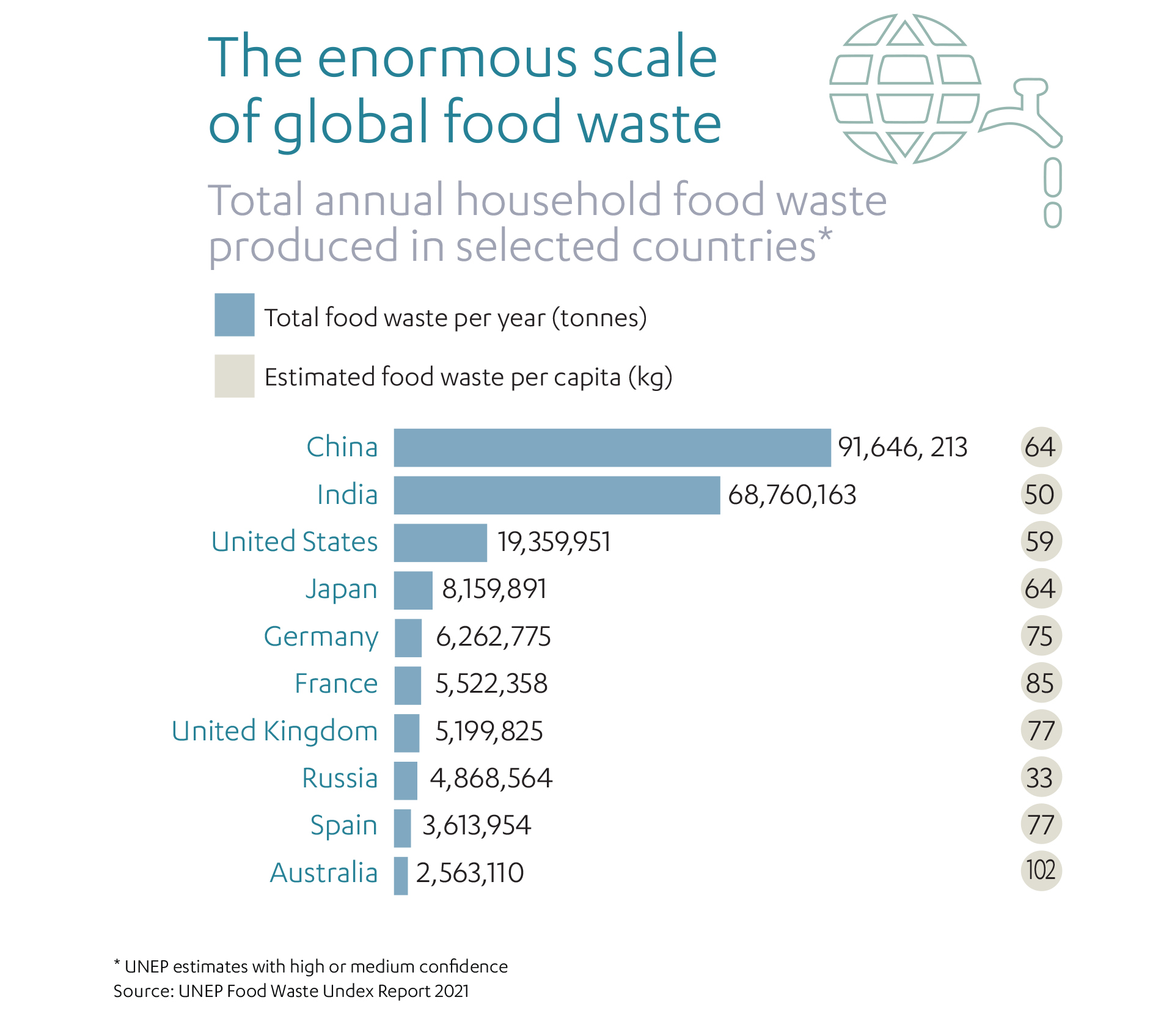

What is less expected, however, is that one of the other main causes is wastage: around one-third of the world’s food is squandered annually through wastage or loss.

One-third.

It’s not just that we aren’t producing enough food, it’s that a significant amount of the food we produce is simply wasted, while hundreds of millions of people go hungry.

This erosion of food volume occurs at each stage of the food chain, to differing degrees. By some estimates[2]:

- 13% of food is lost during production

- 6% is lost in transportation

- 1% is lost in processing

- 6% is lost in retail

- 8% is wasted by buyers

So, what’s causing this waste? And more importantly, how do we stop it?

Waste affects the entire food chain

- Production: Our climate is gradually becoming less hospitable for plant and animal life, with rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall. Droughts, floods and increasing pestilence harm crops, while animals being reared for meat wilt, perish and fail to reproduce. Inevitably, food loss during production is predominantly a problem in developing countries, where an urgent demand for food can trigger premature harvests.

- Transportation: Harvests and animals need transporting from point of origin to population centers, but this means adequate freight services and refrigeration facilities. In the developing world especially, too much food is lost due to outmoded technology and underdeveloped transport networks.

- Processing: Some food is consciously discarded for arbitrary reasons because crops fail to meet visual standards, or because repurposing edible offcuts is more expensive than simply disposing of them. Inefficient industrial treatments also damage a proportion of foodstuffs or lower its nutritional value.

- Retail: In shops and eateries further waste occurs. For developed nations, portion sizes can be too large (leading to leftovers later), while over-cautious ‘consume by’ dates encourage a ‘better safe than sorry’ throw-away culture. Cheap packaging allows food to decompose too quickly, which supermarket overstocking is a tactical yet wasteful strategy. In the developing world, poor refrigeration again leads to early spoilage.

- Consumption: We buy too much, we eat too much, we throw away too much. Food rotting in landfills emits methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period[3]. While food waste in the home is observed at every income level, it is predominantly a problem in mature economies. American households waste approximately one-third of their stocks each year, worth some US$ 240 billion[4]. Europe manages to waste more food than it imports every year, with each individual generating an average of 75kg of annual food waste[5].

Having accepted the magnitude of the crisis, we can begin to examine exactly how food loss adds to the growing environmental emergency, and how we can begin to mitigate such terrible wastage.

How waste contributes to climate change

Food doesn’t just magically appear on our plates, so when we ‘waste food’ we sacrifice more than just its nutritional value. We also render wasteful all the energy, human labor, land, water and fertilizers that went into its production.

Further, as discarded foodstuffs decompose, they add to the global tally of greenhouse gases. The UN has calculated the food sector cumulatively accounts for 30% of the planet’s total energy consumption and produces more than one-fifth of toxic emissions[6]. With scientific modelling suggesting several degrees of global warming by the end of the century[7], it is imperative we reverse our gross wastefulness.

![]() Little wonder that UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 (covering responsible consumption and production) aims by 2030 to “halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses”[8].

Little wonder that UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 (covering responsible consumption and production) aims by 2030 to “halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses”[8].

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) aims to hasten this journey. It held its third annual International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste on September 29, 2022.

The initiative aims to encourage all public and private food producers, as well as consumers, to support food security and nutrition. The FAO argues this is best accomplished not by conspiring to grow yet more food, which is a resource-hungry activity, but rather by cutting waste along production and supply chains.

So, where do we start?

Interventions to encourage a healthier food system

Perhaps we begin with climate-smart food technologies and infrastructure – the types of innovations that can prevent food going bad before reaching markets, or reduce food system emissions.

Cheaper, more efficient refrigeration techniques could help establish more ‘cold corridors’, seamlessly linking harvest regions with marketplaces to avoid unnecessary spoilage.

Solar-powered walk-in cool rooms could help farmers in rural areas (often blighted by poor grid connectivity) adopt the food preservation strategies of wealthy multinationals.

In the laboratory, research continues into supplementary peels – specially-made outer skins, produced from organic material, designed to extend the shelf life of perishable foods.

Then we can turn our attention to the human factor: governance, collaboration and ethics. Here, changing long-established behaviors is key.

Better livestock management and a wider embrace of meat-free diets are estimated to save 65-80 tons of methane emissions per year over the next few decades.

In addition, reusing rather than discarding excess foods – either into compost or biogas – could help redefine the very nature of ‘waste’.

Businesses, policymakers and NGOs can all play their part in this mission:

- At production level, public/private partnerships can finance new technologies to help farmers better protect their crops against pests (via organic pesticides) and better preserve those crops post-harvest (via longer-lasting preservatives).

- At the retail level, more responsive inventory technologies can reduce the tendency to overstock, while next-generation packaging can help prevent deterioration.

- At the domestic level, advertising campaigns can help raise shoppers’ awareness of the problem of food waste. Food management apps can help householders monitor expiration dates and even suggest recipes for food nearing the end of its life.

International nonprofit organization Project Drawdown, which aims to curtail greenhouse gases in our atmosphere and ultimately trigger their decline, highlights the profound difference tackling food waste could make to the environment.

International nonprofit organization Project Drawdown, which aims to curtail greenhouse gases in our atmosphere and ultimately trigger their decline, highlights the profound difference tackling food waste could make to the environment.

It has hypothesized two scenarios: one in which total global food loss is reduce by 50% by 2050, and a second in which food loss is cut by 75% by the same date. A 50% cut would translate to 88.50 gigatons of CO2 emissions saved; a 75% cut would translate to 102.20 gigatons of CO2 emissions saved. In fact, Project Drawdown estimates that cutting food waste could help fight world hunger by offsetting some 60% of the global food shortages predicted by 2050[9].

Big data and the internet of things (IoT) can usher in an age of real-time logistics and stock awareness, synchronizing supplies with pricing and use-by dates. In an ideal world, the right produce needs to get to the right locations at the right time – preferably in the most fuel-efficient manner. Local sourcing is the future, wherever possible, heralding social as well as environmental benefits.

Businesses, for their part, can be encouraged to adopt ‘food waste’ as an official performance metric – a promising scenario given the recent trend toward ethical, social and governance (ESG) investing.

It’s good to know that opportunities exit for tackling the scourge of food waste. These strategies will come together much more quickly if policymakers put in place the right legislative frameworks.

Laying the groundwork for a waste-free world

Since 2016 multiple countries and companies worldwide have signed up to the World Resources Institute’s Food Loss & Waste (FLW) Protocol, which establishes a standardized set of reporting tools for consistently measuring food loss and waste. What can be correctly identified can thereafter be precision-targeted for solutions.

Since 2016 multiple countries and companies worldwide have signed up to the World Resources Institute’s Food Loss & Waste (FLW) Protocol, which establishes a standardized set of reporting tools for consistently measuring food loss and waste. What can be correctly identified can thereafter be precision-targeted for solutions.

The FLW aims to incrementally improve the food security of people and countries; to raise farmer incomes; to lower costs for end consumers and companies in the food value chain; and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and demands for water and energy.’[10]

National policies are beginning to swing behind the food waste challenge.

Mirroring laws passed in France and Italy, Spain this year announced it would fine supermarkets for failing to donate surplus food to charities or NGOs. Likewise, Spanish restaurants will be compelled to provide food bags for customers to preserve leftovers – part of a bid to cut the country’s annual 1,300-ton food waste mountain[11].

Elsewhere, in fall 2022 New York City rolled out a new curbside compost program.

Elsewhere, in fall 2022 New York City rolled out a new curbside compost program.

The city’s 2.2 million residents discard some 10,000 tons of household waste annually – up to one-third of which could be compostable.[12]

Some countries are now offering tax breaks to businesses and individuals donating surplus perishables to food banks, with Canada, Colombia and Argentina making recent headway.[13],[14] Demonstrating the importance of robust legislation, donations to food banks in Argentina increased 119% a year after the country’s Food Donation Law was refined to cover public liability – a wise inclusion, given the inherent risks of distributing produce typically past its prime.[15]

The European Commission launched a Farm to Fork Strategy in 2020, part of its Green Deal, including proposed changes to ‘best before’ and ‘use by’ labelling across the EU. Critics complain that its remit is too narrow, prioritizing consumer and retail waste when at least 30% of the EU’s food waste occurs pre-retail.[16]

The food waste challenge cannot be solved overnight, so the drive to change attitudes must continue. In the USA, legal teams and campaign groups are pressurizing the government to ensure food waste becomes a central plank of its 2023 Farm Bill. The coalition is championing a range of strategies, from financial support for composting facilities, to regional supply chain coordinators, to a ‘good Samaritan’ clause covering civil liability[17].

As with so many of the challenges facing our civilization, inspiring efforts are under way at every level of society, from international collaborations to community action.

Without doubt the private sector must also play its part, deploying its collective financial resources to energize the food waste fightback.

Funding innovative food waste solutions

As private investors, beholden neither to shareholder whims nor the transitory nature of politics, we can target our speculative capital at future technologies to help overcome the world’s nutritional challenge.

Private capital is patient, long-term, and squarely focused on the cutting edge.

The Abdul Latif Jameel Water & Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS), co-founded in 2014 by Community Jameel and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, funds several projects destined to combat food waste.

The Abdul Latif Jameel Water & Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS), co-founded in 2014 by Community Jameel and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, funds several projects destined to combat food waste.

J-WAFS’ research projects include:

- Developing hybrid evaporative / radiative cooling techniques to extend the edible life of foods in rural areas

- Introducing genetic variations to the DNA of crops to make them more resistant to warmer temperatures and drier conditions

- Using metabolic engineering to convert dairy industry waste into food and feed ingredients

- Detecting pathogens at processing sites to cut down on food recalls

- Developing vaccines for the aquaculture industry to keep protein-rich fish stocks healthy.

J-WAFS also partners with Rabobank on the annual Food and Agribusiness Innovation Prize. Projects include a joint MIT / Tufts University scheme to develop natural protein-based coatings extending the shelf life of perishables by up to 50%.

Since J-WAFS’ foundation, it has financed 60+ projects, generating more than US$ 12 million in follow-on funds.

Away from the corporate world, we can each make a difference next time we stand in the supermarket aisle, order in a restaurant, or open the refrigerator door.

We must repress our urge to exploit buy-one-get-one-free deals which lead to wastage; we must overcome our expectation that seasonal fruit and vegetables from all over the world should be available all year round; we must stop over-ordering in restaurants and cafes and assuming our leftovers will meet some productive fate; and we must become less wedded to expiration dates which scare us into disposing of perfectly good food.

It is morally obscene that while multiple millions of souls struggle for sustenance every year, we collectively sacrifice mountains of food which could help alleviate the problem.

For wealthy societies, it is a matter of financial recklessness. For poorer societies, it can be a matter of life and death. And for the planet, food waste is another battleground in the ongoing and existential war against climate change.

[1] https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/world-hunger-facts

[2] https://www.bcg.com/featured-insights/closing-the-gap/food-waste

[3] https://www.fao.org/3/cc1092en/cc1092en.pdf

[4] https://www.forbes.com/sites/lanabandoim/2020/01/26/the-shocking-amount-of-food-us-households-waste-every-year/?sh=da06cb7dc8e3

[5] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1219830/per-capita-food-waste-of-selected-countries-in-europe/

[6] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/

[7] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01125-x

[8] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/

[9] https://drawdown.org/about

[10] https://www.wri.org/initiatives/food-loss-waste-protocol

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/07/spain-fights-food-waste-with-supermarket-fines-and-doggy-bags

[12] https://www.ecowatch.com/curbside-composting-nyc.html

[13] https://www.ifco.com/how-incentives-could-reduce-food-waste/

[14] https://www.foodbanking.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Colombia-Recommendations.pdf

[15] https://www.ifpri.org/blog/improving-food-donation-policies-key-fighting-food-waste

[16] https://www.ecowatch.com/farm-to-fork-europe-2646908613.html

[17] https://www.ecowatch.com/reducing-food-waste-farm-bill.html

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit