Islands of hope

There are so many facts and figures published about climate change. So many complex policies and programs; visions and principles. All very useful. Certainly very necessary. Nevertheless, amid the complexity, sometimes it’s easy to forget the very simple truth about global warming: our planet, as we know it, is at risk. Society will undergo irrevocable change. Our economies will be decimated.

I’ve previously written about how the climate crisis is changing the circadian rhythms of our natural environment, how it’s changing our weather patterns, raising temperatures and threatening our food and water systems. It’s not only our individual livelihoods, homes and communities that face this existential threat. Entire countries could disappear off the map, sinking beneath the ever-rising seas of our stricken planet.

It may sound like something from a dystopian sci-fi movie, but it is already happening. Take the Maldives, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean most well known as a luxury holiday destination. Some 14 years ago the Maldives elbowed its way to the front of the debate on climate change.

Its president, Mohamed Nasheed, plus 11 ministers, the vice president and the cabinet secretary, held a 30-minute cabinet meeting at the bottom of a four-meter-deep lagoon. In scenes broadcast around the world, they scrawled “SOS” on a white slate. The point, so strongly made, was that much of the Maldives would disappear beneath the waves if the current rate of climate change and rising sea levels continued unabated.

This act of political theatre might have seemed more in keeping with youthful demonstrators than serious politicians, but it drew attention not only to the Maldives but also to the plight of low-lying countries and regions across the globe, setting an agenda that has become even more relevant in the years since. Staged ahead of the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Summit in Copenhagen, the stunt provided a platform for President Nasheed to declare that if the Maldives went under, then so would much of the rest of the world.[1]

In the United States, almost 30% of the population lives in coastal areas, where sea level plays a role in flooding, shoreline erosion, and hazards from storms. Globally, 8 of the world’s 10 largest cities are near a coast, according to the UN Atlas of the Oceans.[2] But it is low-lying islands nations like the Maldives that are on the front line of this battle.

Prehistoric Atlantis

It is not the first time the world has faced rising sea levels that swamp inhabited lands – but it has not happened for many thousands of years. More than 8,000 in fact. Doggerland[3] was a massive area – nearly 46,620 square kilometers – between Britain and the European mainland that was submerged as ice-age glaciers melted and inundated the land to create the North Sea[4].

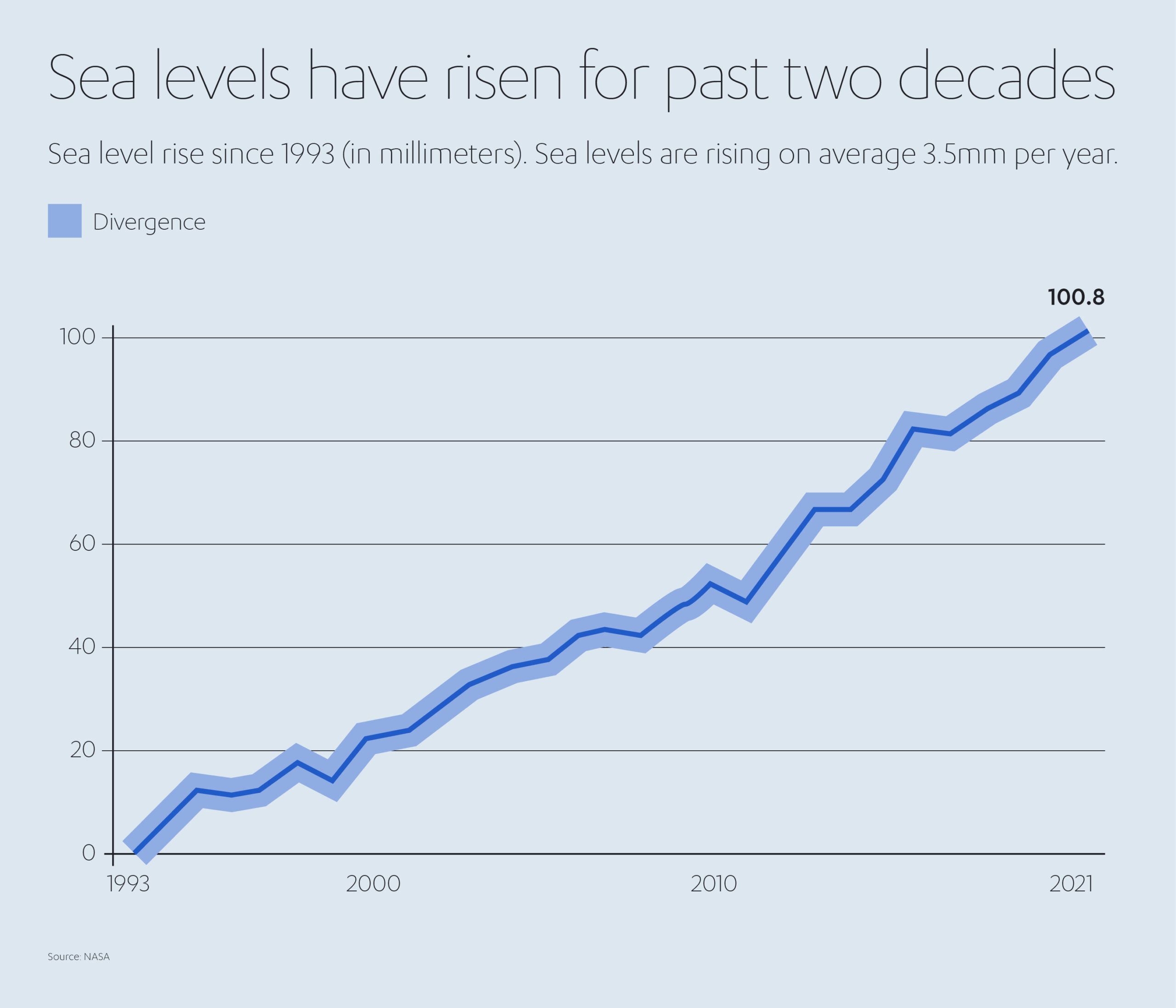

There have long been myths of sunken cities, such as Atlantis, and underwater worlds, but today these myths are well on their way to becoming a reality. Sea levels are rising faster than at any time over the past 6,000 years, with the global sea level 5-8 inches (13-20 cm) higher on average than it was in 1900[5].

The tools to measure the global sea level are far more accurate than even 25 years ago. Where once we relied upon tide gauges fixed to a structure such as a pier, we now use satellites that bounce radar signals off the ocean’s surface[6]. Both measures show the sea is not only rising, but rising more quickly. Between the year 1900 and 2000, the global sea level rose between 0.05 inches (1.2 millimeters) and 0.07 inches (1.7 millimeters) per year on average. In the 1990s, that rate jumped to around 3.2 millimeters per year[7].

Countries based around atolls and archipelagos are all at high risk of disappearing. The low-lying ones most immediately threatened are principally in the Pacific and Indian Oceans and include Kiribati, the Maldives, Fiji, Palau, Micronesia, the Solomon Islands, the Seychelles, the Torres Strait Islands, Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands and the Carteret Islands.

The Carteret Islands of Papua New Guinea provide a snapshot of what might be in store for the rest. This atoll is currently made up of five low-lying islands scattered in a 19-mile-long horseshoe shape. Already, it is estimated that its landmass is less than 40% of what it was originally – when there were seven islands. Many inhabitants have either been forced to leave their homes for higher ground or resettled somewhere else. Ursula Rakova, from the islands’ relocation organization, attended COP 27 in Egypt in 2022 to ask for US$ 2 million to move 350 families to the mainland.

Strategies for the future

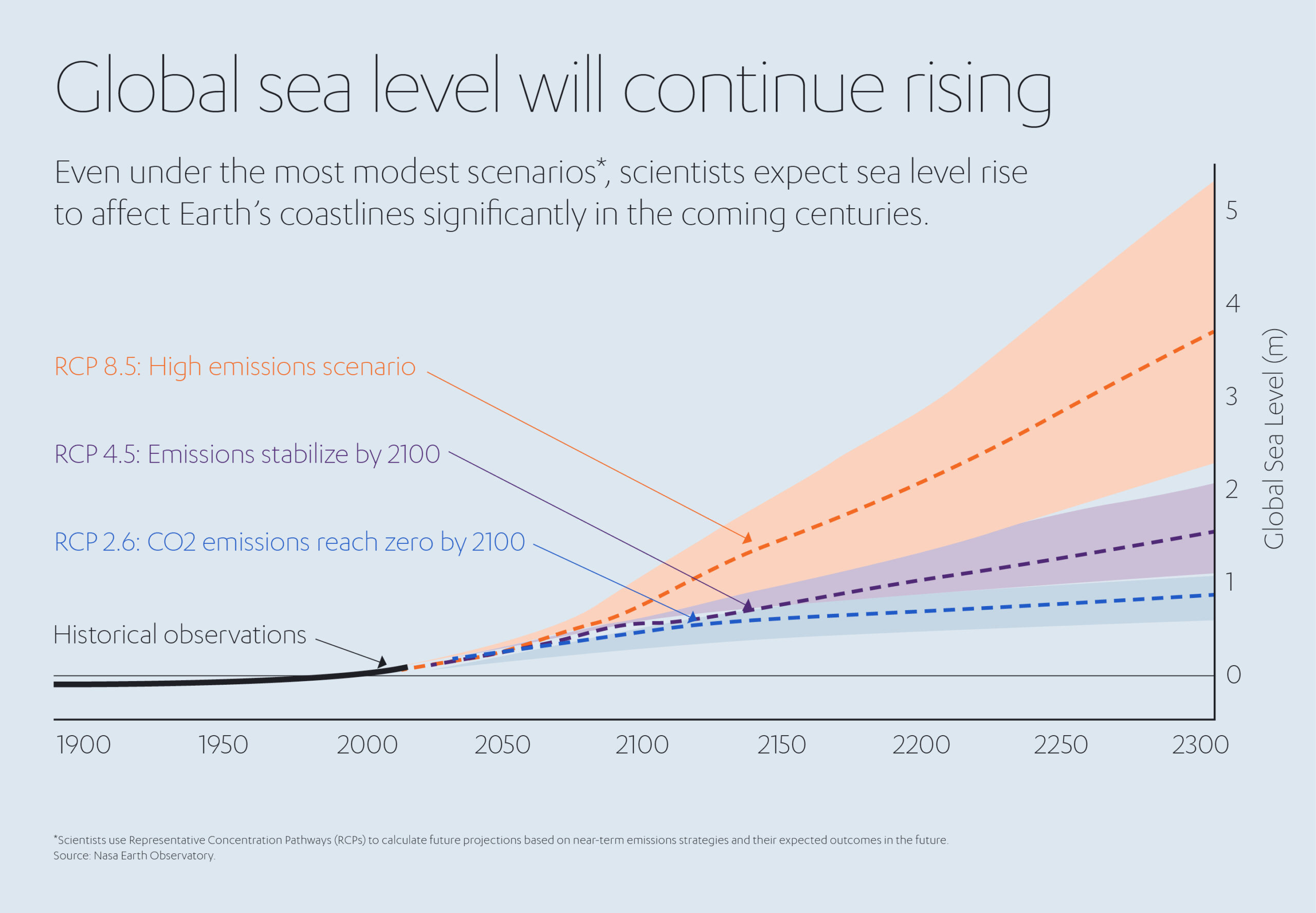

For most of the affected countries, the long-term answer is to cut greenhouse gas emissions and stop the sea levels rising, but it could well be too late for that. Rising seas are caused by the combination of a number of different processes, including the warming of the ocean, and the melting of glaciers—particularly from the massive Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Both of these processes may continue long after human-caused greenhouse gas emissions have come to a halt. The melting of the ice sheets, in particular, is a process that may be difficult to stop once it is set in motion. Even after global temperatures stabilize—and even if they stabilize within the 2oC threshold outlined under the Paris Climate Agreement—the warming that occurs up to that point may destabilize the glaciers to an extent that continued ice loss becomes unstoppable far into the future.

The islands at risk are now planning for their future.

Short term, they need to find some way of adapting to rising sea levels and reducing their vulnerability. Long term, the islands are looking for solutions that first, guarantee their citizens a safe place to live, and then ways of preserving both the legal rights and the legacy they had when their country was above the waves. Any solution is likely to be enormously expensive, which is why these largely small, island nations would like those countries that have benefited from the causes of climate change to pay towards dealing with its environmental effects.

Reducing vulnerability

Land reclamation, seawalls and artificial reefs are among some of the technological solutions being considered as having the potential to provide relief, if only in the short term.

One of the most recent initiatives in the Maldives is to create more land. In 2022, the Maldives government commissioned a major shore protection and land reclamation scheme[8] using sand dredged from a lagoon. The development will create 194 hectares of land, including three new island four-star resorts, in the southern atoll of Addu City. The scheme will reportedly cost US$ 147.1 million and be funded via the Export-Import Bank of India (Exim Bank), on behalf of the Government of India[9].

As with many remedial works, there are drawbacks. The first, somewhat ironically, is environmental. According to Van Oord, the Dutch contractor responsible for the development, up to 5 million cubic meters of sand will be dredged from a lagoon in the middle of the six islands, which are home to at least 20,000 people. Other estimates put the amount of sand to be removed at 6.9 million cubic meters. Environmentalists argue that dredging all this sand will raise sediment that could choke the nearby ecosystems and affect their ability to recover in the long term, while reclamation could bury 21 hectares of corals and 120 hectares of seagrass meadows.

Planners have also enhanced the resilience of the country’s current islands through creating new ones. For example, Hulhumalé[10] is a newly constructed artificial island designed to relieve crowding in the capital, Malé. Work began in 1997 in a lagoon near the airport and has since grown to cover 4 km2, making it the fourth largest island in the Maldives. Hulhumalé’s population has swollen to more than 50,000 people, with 200,000 more expected to eventually move there.

The new island, built by pumping sand from the seafloor onto a submerged coral platform, rises about two meters above sea level, about twice as high as Malé itself. The extra height could make the island a refuge for Maldivians who are eventually driven off lower-lying islands due to rising seas. It could also prove to be an option for evacuations during future typhoons and storm surges[11].

Hulhumalé is not the only island in the Maldives that has seen major changes since the 1990s. Reclamation projects have enlarged several other atolls in similar ways in recent decades. Among them is Thilafushi[12], a lagoon to the west that has become a fast-growing landfill, and Gulhifalhuea, the site of another land reclamation project that is opening up new manufacturing and industrial space.

Science of seawalls

Seawalls are often cited as another potential solution to protect low-lying communities from encroaching seas, but the picture here is mixed, too. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that using seawalls as a means of protecting against sea level rise and storm surges can be counterproductive[13], as they can often cause more problems than they solve by interfering with the local coastal ecosystem. They can increase flood risks, for example, by forcing rising waters to find new escape channels, while walls on beaches can block animals like turtles from reaching parts of the beach required for breeding.

There is there is also evidence[14] that sea walls might impede the natural processes that can make coral reef atolls, such as those in the Pacific and the Maldives, more resistant to sea level rises. According to studies, most coral atoll islands in the Maldives and elsewhere have either remained stable or grown larger in recent decades. Researchers at the University of Plymouth, UK, conducted a study[15] based on a scale model of Fatato Island in Tuvalu in the South Pacific. It found that the storms and floods that wash over islands can move offshore sediment onto the island surface, building the island up in the process, but a seawall would stop this happening.

“An island completely enclosed by a seawall is not able to adjust to rising sea level as flooding is prevented, and it is floods that bring in the sediment required for building the island up,” said Gerd Masselink, co-author of the Plymouth report. “Such islands will probably be uninhabitable in 20-50 years or so, unless the seawall is upgraded to deal with the elevated sea level.”

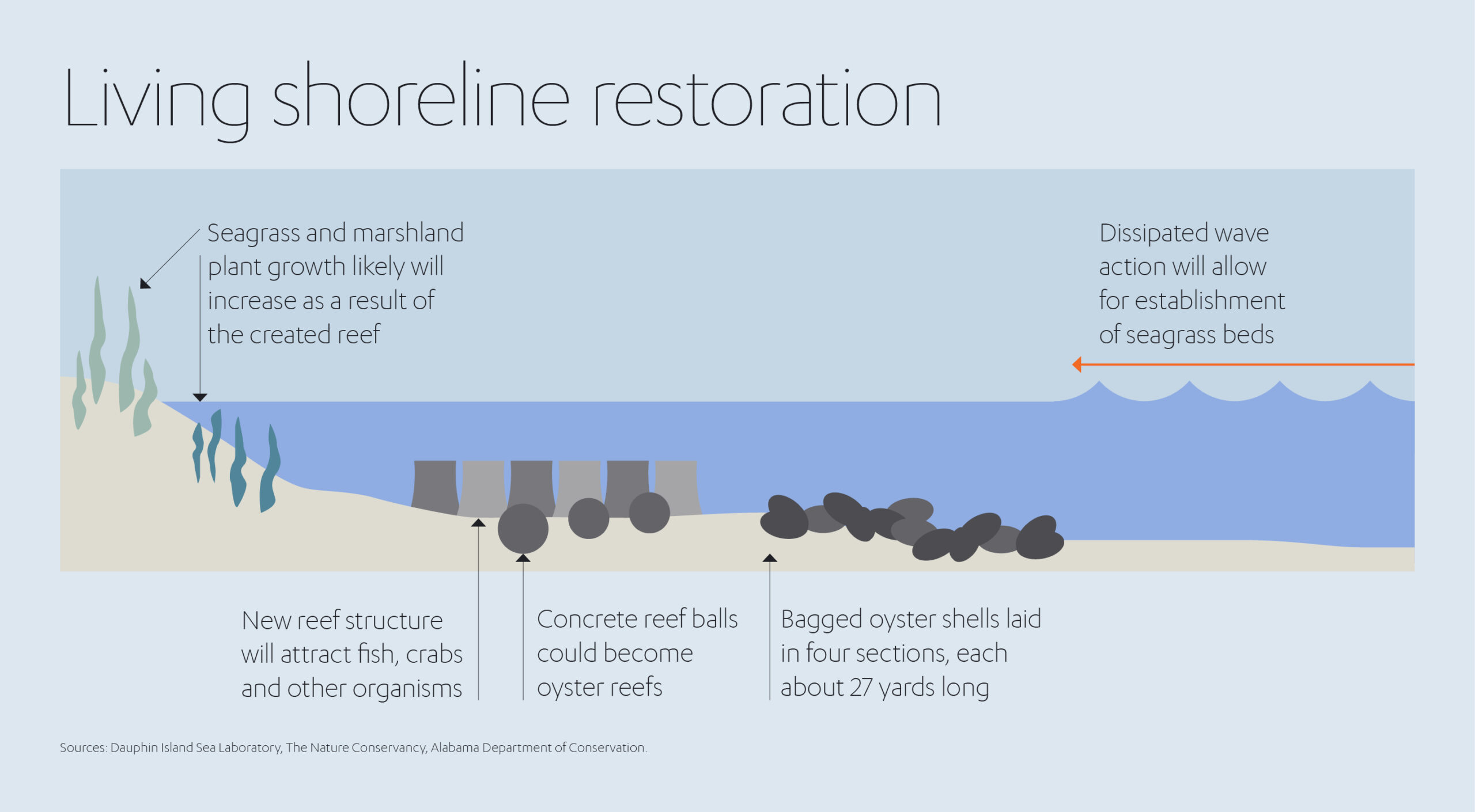

Experts suggest that nature-based solutions like mangroves[16] are generally a better way of dealing with sea level rises than hard infrastructure like seawalls and levees and are usually cheaper. But planting mangroves is not always possible, particularly in urban areas. To gain the best of both, engineers are examining combinations of green and grey infrastructure, like seawalls with a belt of mangroves in front.

Innovative solutions

One option that shows promise is artificial reef restoration to reduce wave heights and stabilize beach widths[17]. A pilot project in the United States used ‘reef balls’ to create artificial reefs. Reef balls are concrete half-spheres with holes in them that allow fish and other marine life to swim through. The project in Connecticut[18], one of several similar schemes across the country, found the balls reduced wave heights by half and lessened wave energy by an even greater factor, simply by breaking waves before they reached the shore.

Another approach being tried out is to ‘go with the flow’ and build developments that float.

As one of the wealthiest threatened islands, the Maldives has been able to partner with architects Waterstudio and Dutch Docklands to create the Maldives Floating City[19].

The development will be constructed within a 200-hectare lagoon near Male and will contain 5,000 low-rise floating homes. The city will be built upon a series of hexagonal-shaped floating structures that will rise as sea levels rise, while artificial coral banks attached to the underside will stimulate natural coral growth. Each seafront residence will be 100m2 and will have a jetty attached to its front and a terrace on its roof.

Heritage preservations

Technology and innovation may well hold the answer for islands learning to live with rising sea levels, but in the meantime, some are looking ahead, working out how to preserve their legal status and heritage. The island nations are having to grapple with what it might mean if their homeland becomes, like Doggerland, a series of sandbanks and rocks. Are you still a country if you’re underwater?

For the Pacific islanders affected, the answer is an emphatic “YES”. In 2022, Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands launched the Rising Nations Initiative (RNI) at the UN headquarters[20]. The RNI is a mixture of the pragmatic and the future proofing. It wants international support to create a comprehensive program to build and finance adaptation and resilience projects that will help sustain local communities’ livelihoods in the face of climate change. But it also wants to preserve its heritage through establishing a living repository of the culture and unique heritage of each Pacific atoll island country and then providing support to acquire UNESCO World Heritage designation. Just as importantly, though, it seeks a political declaration from the international community to preserve the sovereignty and rights of Pacific atoll island countries[21].

Protecting sovereignty

If an island is submerged and its population moves elsewhere, then what happens to all the rights that they enjoyed over the land and the surrounding sea? If, for example, valuable mineral deposits were found, to whom would they belong?

The Pacific Islands Forum[22], a regional body comprising 18 Pacific Island member countries and territories, has made its position clear. It declared in 2022 that its maritime boundaries will be fixed regardless of any changes to the size or shape of the islands in the future. Those boundaries are determined by the size of the member countries’ land masses under the UN Convention on Law of the Sea, but it is still a contentious approach.

Yet there are precedents of a sort. In 2022, a study group[23] set up by the International Law Commission presented alternatives aimed at safeguarding the statehood of nations that may lose their territories due to sea-level rise. It looked at the Holy See and the Sovereign Order of Malta, both of which have some form of international legal personality even though neither has a defined territory, and suggested that the same concept could be applied. This would presume the continuity of statehood – even if that state had no territory.

Vanuatu has taken a legal route, pushing the International Court of Justice[24] to clarify how existing international laws can be employed to address climate change. It has asked for a ‘non-binding advisory opinion’ on the obligations of states under international law to safeguard the rights of current and future generations from the harmful effects of climate change. This would bolster the legal framework around climate change and encourage countries to take stronger action.

Rising sea levels clearly endanger many of the world’s lower lying islands, yet there is still cause for hope as the ingenuity of the responses have shown. Floating cities, for example, do not require any land reclamation and so have a minimal impact on the coral reefs, while encouraging new, giant reefs to grow and act as water barriers[25]. As Maldive’s former President Nasheed, puts it: “We cannot stop the waves, but we can rise with them.”

Blue-sky ideas such as floating islands also show the role that private capital can play. Private investors can take a long-term view rather than constantly requiring short-term profits, giving them the freedom and agility to back the type of innovative technology that makes a difference. It is a challenge to be sure, but not one to be ducked. We should not lose sight of the fact that many of our most populous cities and most productive regions are sited below sea level.

The return on any investment may not only be financial, but it could also very well be existential.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/oct/11/mohamed-nasheed-maldives-rising-seas

[2] https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

[3] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/doggerland/

[4] https://www.newscientist.com/article/2261173-tiny-island-survived-tsunami-that-helped-separate-britain-and-europe/

[5] https://ocean.si.edu/through-time/ancient-seas/sea-level-rise

[6] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/rising-sea-levels-global-threat/

[7] https://ocean.si.edu/through-time/ancient-seas/sea-level-rise

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/may/23/maldives-plan-to-reclaim-land-for-tourism-could-choke-the-ecosystem#:~:text=The%20low%2Dlying%20island%20nation,on%20this%20Unesco%20biosphere%20reserve.

[9] https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bc6264e026ad4fa3afbf6f8b1c794cf1

[10] https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148158/preparing-for-rising-seas-in-the-maldives

[11] https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148158/preparing-for-rising-seas-in-the-maldives

[12] https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148158/preparing-for-rising-seas-in-the-maldives

[13] https://www.climatechangenews.com/2022/03/03/scientists-warn-seawalls-can-make-rising-waters-worse-in-the-long-run/

[14] https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148158/preparing-for-rising-seas-in-the-maldives

[15] https://www.newsweek.com/coral-reef-islands-doomed-sea-level-rise-scientists-1509915

[16] https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-4-sea-level-rise-and-implications-for-low-lying-islands-coasts-and-communities/

[17] https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-4-sea-level-rise-and-implications-for-low-lying-islands-coasts-and-communities/ 4.4.2.3

[18] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reef-balls-gain-traction-for-shoreline-protection/

[19] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/maldives-floating-city-climate-change/

[20] https://apnews.com/article/united-nations-general-assembly-drowning-island-nations-75f5390daf98d1d385da7dd4a869ae09

[21] https://climatemobility.org/rising-nations-initiative/#:~:text=The%20Rising%20Nations%20Initiative%20puts,%2C%20rights%2C%20culture%20and%20heritage.

[22] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/amid-rising-seas-island-nations-push-for-legal-protection

[23] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/amid-rising-seas-island-nations-push-for-legal-protection

[24] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/amid-rising-seas-island-nations-push-for-legal-protection

[25] https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/maldives-floating-city-climate-change-b2108523.html

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit