COP29: Bold enough to make a difference?

Assessing the key outcomes of the UN’s annual global climate change conference

The timing of COP29 in November 2024 demonstrated one unassailable truth – climate change action is dictated by forces more complex than graphs and data points. It is at the mercy of economics, geo-maneuvering, and the kind of political events that can unsettle long-term orthodoxy.

COP29 began in Baku, Azerbaijan less than a week after the election of Donald Trump as 47th President of the USA. Whatever actions were agreed at COP came in the context of a US leader who aimed to reassess environmental protections and reinvest in fossil fuels. Indeed, President Trump’s first 100 days in office saw his administration withdraw funding for science programs, approve new oil pipelines, and pull America out of the landmark 2016 Paris Agreement on climate change[1]. All of which makes the steps agreed at COP29 all the more critical as we enter a new phase of climate action around the world.

Delegates from almost 200 countries at COP29 provided a watchful world with many reasons for optimism, culminating in a host of new measures designed to neuter the extremes of global warming, and to more effectively deal with its impacts.

Most notably, a new US$ 300 billion climate finance fund was agreed on for developing countries, with annual payments due to begin by 2035.[2] As a commitment, it represents a huge increase on the US$ 100 billion a year currently offered.

The fund – formally known as the New Collective Quantified Goal – is designed to help emerging markets invest in renewable energy and abandon their reliance on fossil fuels. As climate impacts mount, it will also help maintain vital services like hospitals, schools and industry, protecting communities from harm and ultimately keeping societies viable.

The rolling obligation will be met from a combination of public and private sources, with developed countries taking the lead. A joint statement from multilateral development banks (MDBs) at COP29 noted a corresponding 25% rise in climate financing over the last 12 months.[3]

EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra hailed the fund as nothing less than a “new era on climate finance”.[4] It was far from the only initiative emerging from COP29 to offer hope in the race-against-time battle with climate change.

What changes were made around carbon trading & NDCs?

To maintain any hope of restricting global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrialization levels (the core tenet of the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit extreme weather, rising sea levels and biodiversity loss) the world needs – as one tool – an active and functioning carbon market. Fittingly, COP29 finally formalized an international carbon market agreement, setting universal standards which will validate a centralized crediting mechanism and foster an ecosystem of bilateral carbon trading[5].

The deal specifies how countries can authorize the trading of carbon credits, and outlines plans for the registry that will monitor their movement. To boost legitimacy, it formalizes ongoing technical reviews ensuring environmental integrity and transparency.

It is hoped that a surging carbon market will improve access to finance in emerging economies, in particular helping the least-developed nations to develop climate-resistant infrastructure.

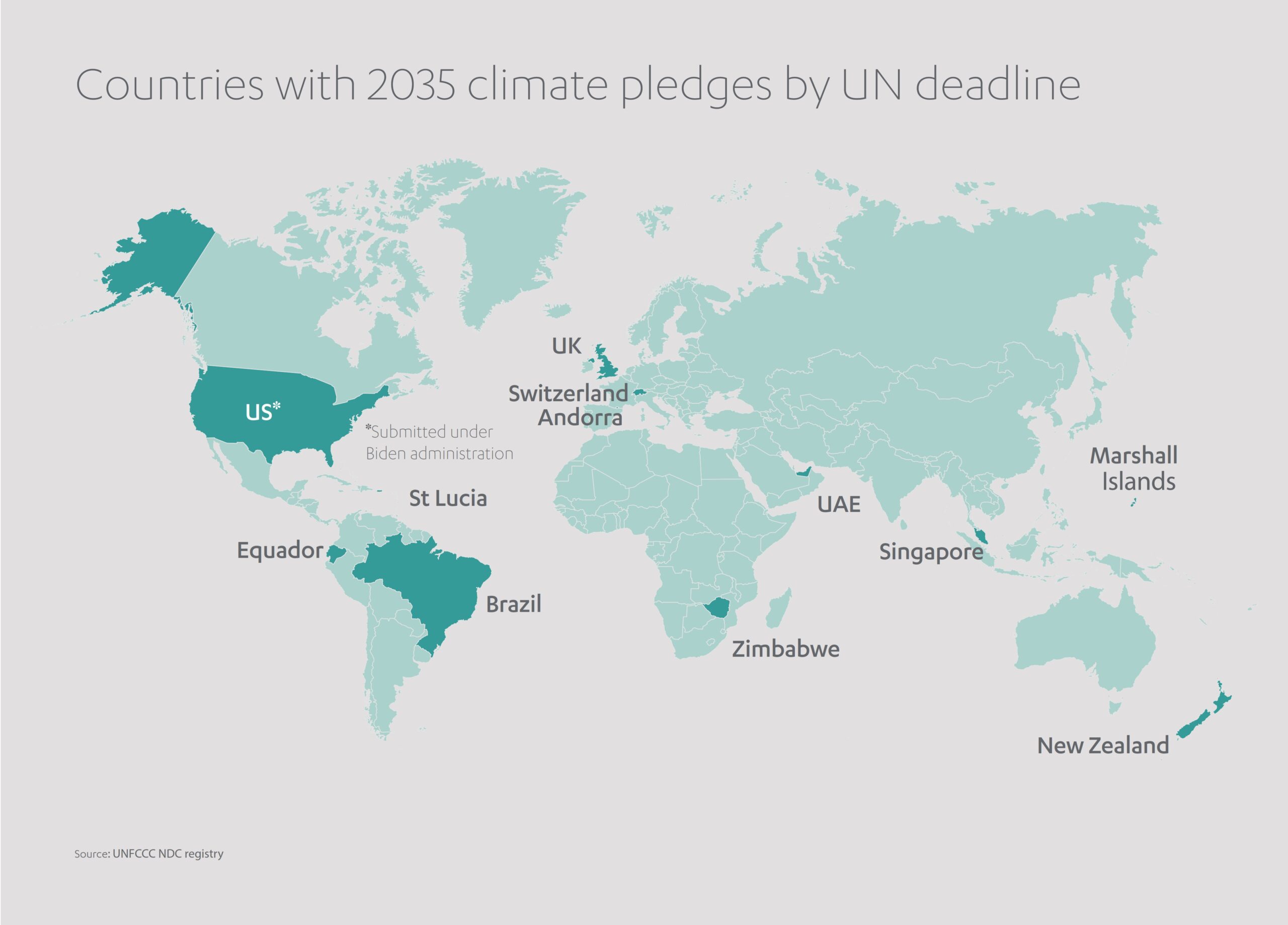

COP29 also saw a raft of updated Nationally Defined Contributions (NDC) unveiled by attending nations. NDCs reflect individual pledges, unique to each country’s circumstances, to cut greenhouse gases and adapt for a future potentially dictated by accelerating climate change. They dictate emission cuts for sectors deemed heavy polluters, such as transport and energy, while guiding national climate policies and spurring investments.

Among NDCs announced, the UK has arguably embarked on one of the most ambitious trajectories with newly elected Prime Minister Kier Starmer pledging that by 2035 the UK would cut all fossil fuel emissions by 81% based on 1990 levels.[6]

Brazil, set to host the next COP gathering in Belem, Brazil, in November 2026, took the opportunity to announce that by 2035 it would reduce its GHG emissions by 67% based on baseline 2005 figures.[7] The United Arab Emirates, meanwhile, pledged a 47% drop in emissions by the same date, based on levels recorded in 2019.

Subsequent to the conference, several other major economies have fulfilled their promise to confirm their own improved NDCs. In the US, the twilight days of the Biden government saw officials outline a new goal of cutting emissions by 66% (relative to 2005 levels) by 2035. Canada announced an emissions reduction target of 45%-55% by the same date. And Japan pledged a new goal of achieving 60% cuts (based on 2013 figures) by 2035, a sharp uptick from its interim target of 46% by 2030. Other nations are expected to follow suit, unveiling radically supercharged NDCs before the eyes of the world turn to COP30 in Brazil.

How much new funding was agreed at COP29?

Apart from its headline breakthroughs, COP also provided an opportunity for stakeholders in regulation, finance, and science to converge and form new public-private partnerships.[8] The more promising of these alliances will help deliver new energy storage capacity, usher through the next generation of climate technologies, and oversee mass reforestation – all pivotal responses to the new climate paradigm.

The Asian Development Bank announced a US$ 3.5 billion climate adaptation program to mitigate the impacts of glacier glacial melt on the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia[9]. Communities and businesses will be helped to adapt to the impacts of melting glaciers, in particular by encouraging sustainable water management and food security.

Investment firm Acumen pledged a five-year US$ 300 million fund to bankroll agricultural adaptation projects in Africa, Pakistan, India and Latin America[10]. The scheme aims to reach 40 million smallholder farmers and feed upwards of one billion people.

Climate Investment Funds (CIF), offering highly subsidized funding to eco-projects as a honeypot for private investment, used COP29 to announce a new listing on the London Stock Exchange[11]. The move could raise some US$ 75 billion for climate action over the next decade.

The Association of Banks of Azerbaijan, meanwhile, encompassing chief finance figures from the host country, revealed it had ringfenced US$ 1.2 billion to help smooth the country’s transition to a low-carbon economy. The banks will collaborate with parallel institutions in other markets to attract additional funds, and in time will expand to issuing green bonds[12].

The Financing Asia’s Transition Partnership (FAST-P), an initiative launched in 2003 by the Monetary Authority of Singapore, also took a major step towards credibility at COP29. It sealed a series of new international partnerships on its way to accumulating a US$ 5 billion investment fund, one spanning multiple transition projects currently in the pipeline across Asia[13]. FAST-P’s Industrial Transformation Infrastructure Debt Program won backing from the AIA Group, the International Finance Corporation, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Nippon Export, BlackRock and Investment Insurance. Additionally, FAST-P’s Green Investments Partnership secured around US$ 1 billion sustainable infrastructure funding via Pentagreen Capital, a joint venture between lender HSBC and Singapore state investor Temasek.

Overall, COP29 attracted praise from multiple quarters. UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell hailed the new finance goal as “an insurance policy for humanity”. He added that it would protect billions of lives while helping all countries “share in the huge benefits of bold climate action: More jobs, stronger growth, cheaper and cleaner energy for all.”[14]

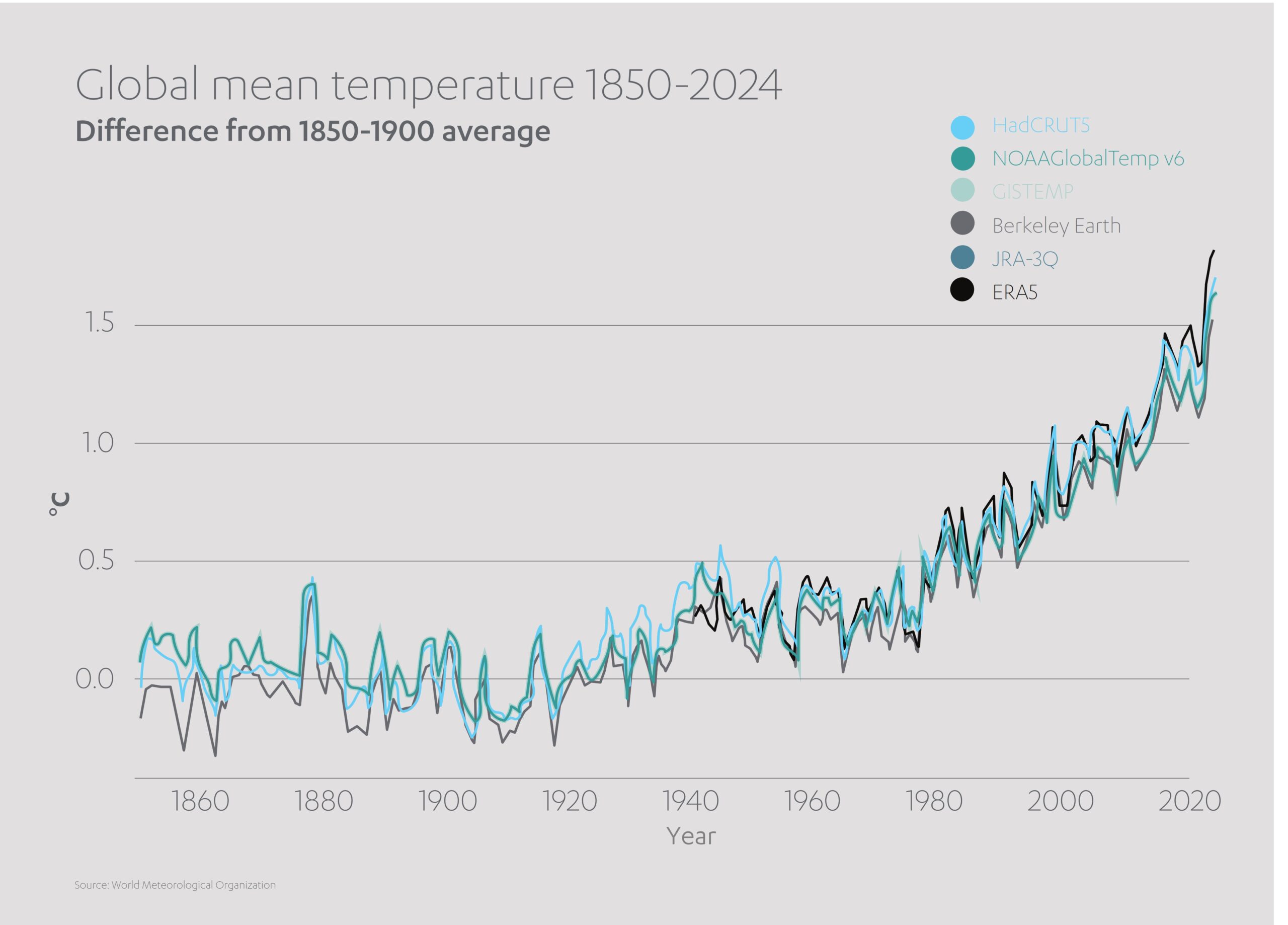

As admirable as these vast ambitions are, COP29 took place in a year already declared the hottest on record. 2024 became the first calendar year with a global mean temperature of more than 1.5°C above the 1850-1900 average.[15] During 2024, more than 150 climate disasters unfolded around the world, including floods, heatwaves and hurricanes. Some 800,000 people were displaced by climate catastrophes, the highest number since records began.[16] Heatwaves generated temperatures alarmingly close to 50 degrees in Iran, Western Australia and Mali. Flash flooding struck communities as far afield as Italy, Senegal, Pakistan and Brazil. Typhoons assailed Asia, while Hurricane Helene was the strongest ever recorded in the Big Bend region of Florida, USA. Global insurance losses from natural disasters were forecast to top US$ 135 billion for the year.[17]

Against this backdrop, dissenting voices wondered why COP29 could not go even further in securing the kind of game-changing commitments necessary in the existential crusade against global warming.

Are global climate targets still on track?

To qualify our praise of COP29’s myriad accomplishments, let us start by revisiting that headline figure: Richer nations pledging at least US$ 300 billion annually from 2035 to fund the fightback against climate change.

Considering the scale of the dilemma, the number was derided in some quarters as a “paltry” amount, one which “will not address the enormity of the challenge we all face”.[18] In reality, the UN Trade and Development intergovernmental organization (UNCTAD) has warned that the true sum needed annually by the mid-2030s to help poorer nations prepare for global warming will be closer to US$ 1.5 trillion.[19]

As a nod in this direction, COP29 did see the adoption of the so-called Baku to Belem Roadmap to US$ 1.3 Trillion initiative[20]. By integrating trade and investment policies into climate plans, and emphasizing the need for policy coherence, the ‘Baku to Belem’ policy provides a blueprint for achieving far greater financial commitments in the crucial coming years. Remember, helping emerging economies cut emissions is one of the surest ways to control rising temperatures, since emerging markets have been the source of three-quarters of all emissions over the past decade.[21]

Similarly, while the launch of the US$ 700 million Loss and Damage Fund (a climate finance mechanism supporting communities with inadequate adaptation strategies) was welcomed, it was noted that the figure fell well below the estimated US$ 150 billion needed to offer genuine redress.

Demonstrating a disappointing lack of urgency, only 13 of the 195 signatories to the Paris Agreement met the February 2025 deadline for submitting their new NDCs – just nine months before COP30 in Brazil.[22] Among the G7 economies, only the USA and UK released their plans on time. Most remaining countries are expected to submit new NDCs by September at the latest. A further caution: The mere existence of an NDC is not proof of its adequacy. Among those NDCs already released, research group Climate Action Tracker has found that those provided by the USA, Brazil, Switzerland and the UAE remain incompatible with global temperature targets.[23]

COP29’s progress in refining carbon markets is to be lauded. Still, much work lies ahead to design robust frameworks and earn carbon credits the global integrity they will require to become meaningful commodities. Developing nations have stressed the need for access to modern financial and technical tools to help them compete in these markets and share their benefits.[24]

COP29’s progress in refining carbon markets is to be lauded. Still, much work lies ahead to design robust frameworks and earn carbon credits the global integrity they will require to become meaningful commodities. Developing nations have stressed the need for access to modern financial and technical tools to help them compete in these markets and share their benefits.[24]

Time is not on our side. The UN Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2024[25], released just weeks before COP29, warned of the stark need for radically upgraded NDCs in order to keep the 1.5 degree plan alive. It called for emission cuts of 42% by 2030 and 57% by 2035 – and it remains to be seen whether the final stock-take of NDCs will match these aspirations. The penalty for failure will be harsh: Global temperature increases of 2.6 to 3.1 degrees this century, along with all the associated social chaos.

Perhaps technology, the subject of much discussion at COP29, will offer us ways to square the circle.

What role is the private sector playing in the climate fightback?

Innovators, investors and policymakers united at CO29 for Technology Day on Transformative Industry, a chance to share knowledge on technical solutions to the global climate crisis. Discussions focused on hard-to-abate sectors such as construction and chemicals, and highlighted the evolution of green hydrogen and carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS).

The COP29 Declaration on Green Digital Action was endorsed by more than 1,000 governments, businesses, NGOs and other stakeholders. The declaration calls for exploiting the benefits of AI, fintech and Big Data to provide solutions around climate monitoring, early warning systems, and agricultural adaptation.

In his opening speech, COP29 President HE Mukhtar Babayev demanded a vibrant system of international technology transfers to ensure no community gets left behind[26].

Technology will indeed be essential, given that COP29’s Action Agenda included a key pledge to increase global energy storage capacity sixfold from 2022 by the end of this decade.[27] Private sector players will prove central to this journey.

I’m pleased that Abdul Latif Jameel – in particular our Energy and Environmental Services businesses – has distinguished itself as a leader in cutting-edge renewable energy and energy storage solutions. Its flagship green energy business Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV), invests in generating green electricity from wind and solar projects across the globe, including Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and Australia. Its innovation arm, FRV-X, pioneers utility-scale battery energy storage schemes (BESS) worldwide. FRV operates more than 50 plants across four continents, totaling 5 GW of energy backed by project financing exceeding US$ 5 billion.[28]

Preparing for a more challenging future, Almar Water Solutions, has a global presence spanning the Middle East, Latin America, Africa, Australia and Asia-Pacific. It develops and manages water infrastructure projects centered around technologies such as reuse and desalination. Its new ventures division, meanwhile, specializes in projects that, through innovation, generate a positive environmental and social impact. Current areas of focus include waste-to-energy, green hydrogen and mineral recovery.

As much as we may wish we could control every facet of our lives, the reality is we cannot. International symposiums like COP29 offer us a rare chance to exert some influence over the macro-crises looming on the horizon. They show that by embedding greater climate awareness around the globe, and adopting forward-thinking policies, we can start shifting the needle on global warming.

COP29 may have underwhelmed some who were hoping for immediate game-changing sums of money to bankroll climate adaptation. However, by advancing an agenda of adventurous finance initiatives, competitive carbon markets and reinvigorated NDCs, it delivered some rays of hope for those seeking even more transformative steps at COP30 later this year.

Five fast facts about COP29

- What was the headline financial commitment agreed at COP29?

A new US$ 300 billion climate finance fund was agreed for developing countries, with annual payments due to begin by 2035 – a huge increase from the current US$ 100 billion per year. - How much funding does the UN estimate is actually needed annually by the mid-2030s?

The UN Trade and Development organization (UNCTAD) has warned that the true sum needed annually by the mid-2030s to help poorer nations prepare for global warming will be closer to US$ 1.5 trillion. - What major climate milestone was reached in 2024?

2024 became the first calendar year with a global mean temperature of more than 1.5°C above the 1850-1900 average, making it the hottest year on record. - How many countries met the UN deadline for submitting new climate pledges (NDCs)?

Only 13 of the 195 signatories to the Paris Agreement met the February 2025 deadline for submitting their new Nationally Defined Contributions (NDCs). - What major carbon market breakthrough was achieved at COP29?

COP29 finally formalized an international carbon market agreement, setting universal standards for a centralized crediting mechanism and fostering bilateral carbon trading.

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-35073297

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp35rrvv2dpo

[3] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/11/12/multilateral-development-banks-to-boost-climate-finance

[4] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/live/c8jykpdgr08t?page=2

[5] https://unfccc.int/news/cop29-un-climate-conference-agrees-to-triple-finance-to-developing-countries-protecting-lives-and

[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-national-statement-at-cop29-12-november-2024

[7] https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/02/cop29-ndcs-and-why-they-matter/

[8] https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/finance-business-deals-announced-cop29-climate-talks-2024-11-13

[9] https://www.adb.org/news/adb-launches-major-initiative-build-resilience-melting-glaciers

[10] https://acumen.org/news/acumen-announces-300m-agricultural-adaptation-commitment/

[11] https://www.cif.org/news/CCMMlisting

[12] https://news.az/news/azerbaijan-pledges-12b-for-green-projects-to-accelerate-low-carbon-transition

[13] https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2024/singapore-commits-us$500-million-in-matching-concessional-funding-to-support-decarbonisation-in-asia

[15] https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-confirms-2024-warmest-year-record-about-155degc-above-pre-industrial-level

[16] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/mar/19/unprecedented-climate-disasters-extreme-weather-un-report

[17] https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/reflections-post-cop29-the-landscape-has-shifted-are-you-adapting-fast-enough

[18] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp35rrvv2dpo

[19] https://unctad.org/news/countries-agree-300-billion-2035-new-climate-finance-goal-what-next

[20] https://unfccc.int/topics/climate-finance/workstreams/baku-to-belem-roadmap-to-13t

[21] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp35rrvv2dpo

[22] https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-95-of-countries-miss-un-deadline-to-submit-2035-climate-pledges/

[23] https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-95-of-countries-miss-un-deadline-to-submit-2035-climate-pledges/

[24] https://unctad.org/news/key-takeaways-cop29-and-road-ahead-developing-countries

[25] https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024

[26] https://cop29.az/en/media-hub/news/cop29-presidency-outlines-plan-to-enhance-ambition-and-enable-action-in-azerbaijan

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit