Redesigning our cities for the 21st Century

Cities embody one of society’s great love-hate relationships: they are the gifts that keep on giving, and at the same time, they are quintessential poisoned chalices.

By Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel

Cities are the engines that have spurred our economies to unprecedented growth and, accordingly, raised living standards to new highs. They have served as melting pots for cultures and fermented ideas that have transformed both commerce and art. They are statements to the world, honey pots for tourism, and stages upon which billions of lives play out, everyday.

Simultaneously, cities have produced some of the worst problems of our age: overcrowding, when population densities have outgrown space; long-term public health failures, when cheek-by-jowl living overwhelms sanitation; choking pollution linked to industrialization and traffic; cyclical periods of mass unemployment and recessions; social dysfunction, and sometimes even conflict, where disparate communities have been thrust together and left to compete for values and resources.

And yet, if there is one thing that cities have consistently demonstrated, it is resilience.

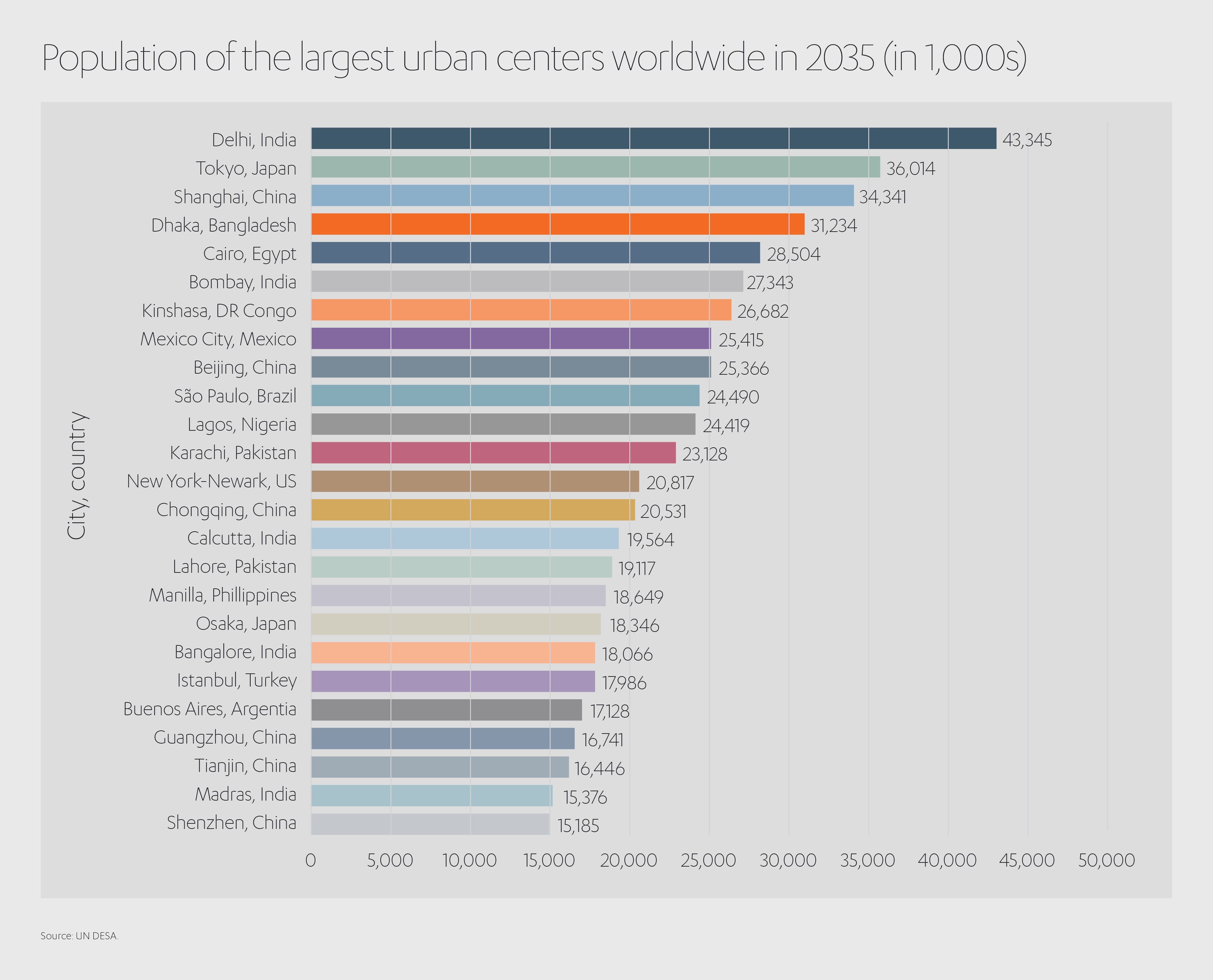

Today, more than half of us (4.2 billion people) dwell in cities, up from less than one-third (751 million people) in 1950. That proportion is predicted to grow to two-thirds in another generation’s time, confirming an uninterrupted trend.[1] Indeed, ten more cities are expected to join the list of ‘megacities’ (10 million+ inhabitants) by 2030, including Luanda (Angola), Hyderabad (India) and Chengdu (China).[2]

Against this backdrop, our expectations of cities are changing at a dizzying rate. History has never moved so fast. Technological opportunities and environmental pressures ensure the future is accelerating towards us at exponential pace. Since the turn of the millennium our attitudes towards the building blocks of society – how we live, how we work, how we move around, how we power of lives – have undergone a series of compelling shifts. What do we want? We want to spend less time commuting and more time with our families and in our homes. We want to work fewer days, more flexibly. We want to enjoy more green spaces, even as our desire for housing grows. We want – no, we need – to cut our pollution, to breathe cleaner air, to consider the needs of our children and grandchildren.

Consider the cities of our world today as a series of test tubes and incubators for better living. They are experiments, with profoundly varied results, revealing how human intervention can help, or hinder, our utopian visions.

And while not all questions are yet answered, one thing seems certain.

If the future is going to be anything at all, it’s going to be smart.

Smarter, faster, cleaner, happier

Smartphones, as their name suggests, will lie at the heart of a smart city revolution. These versatile devices will represent, in the words of leading consultancy McKinsey, “the keys to the city”[3], transmitting real-time information about safety, mobility, jobs, health and leisure directly into the hands of millions.

Consider the fact that few urban planners have the liberty of starting a new city from scratch; most cities come with an infrastructure legacy. The changes we make to them build on the opportunities and errors that have gone before. The data-gathering potential of ‘smart cities’ can help ensure the right decisions are made: long-term, people-focused strategies that respond to changing patterns and tangibly improve life quality.

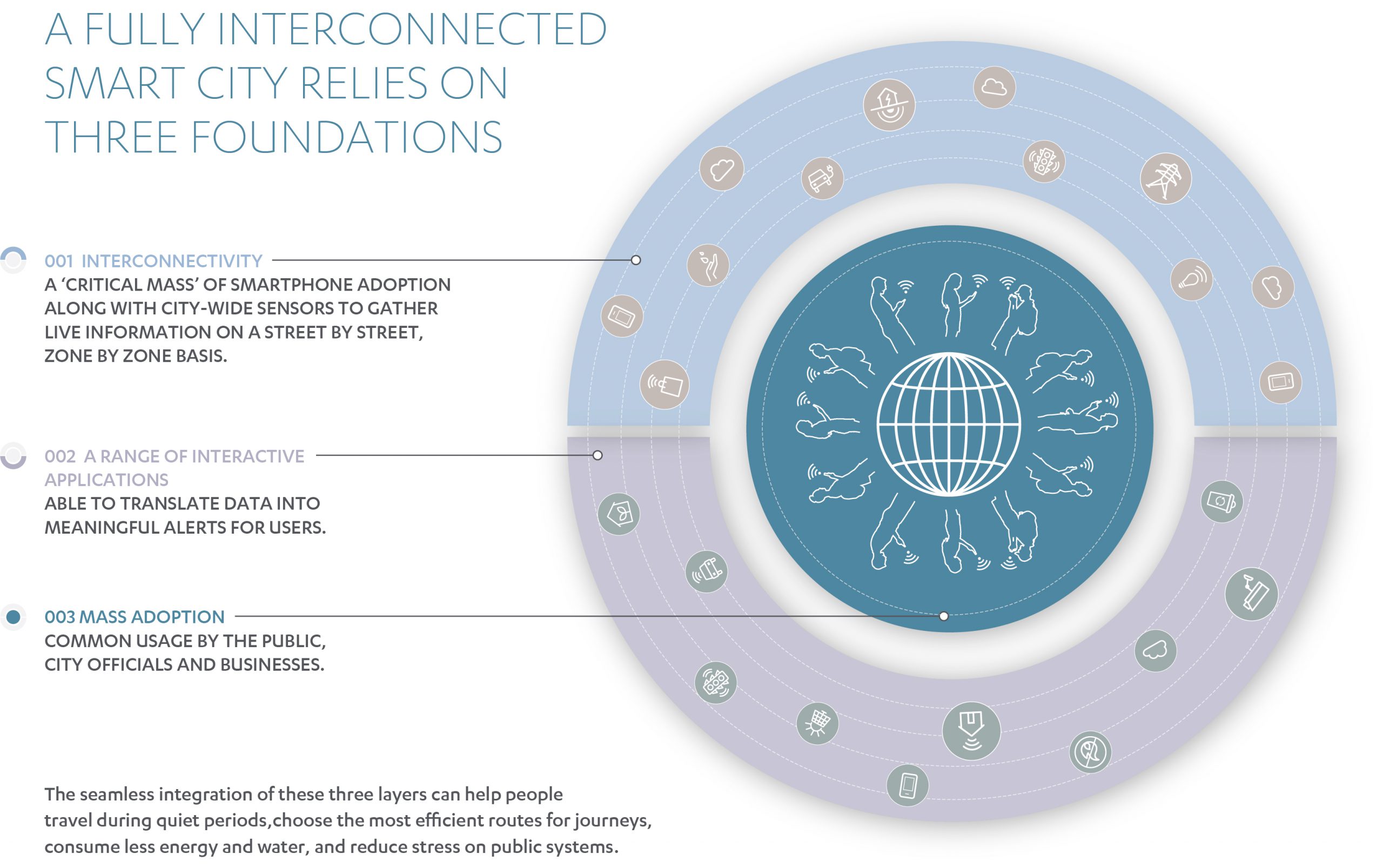

A fully interconnected smart city relies on three foundations. The first is interconnectivity – a ‘critical mass’ of smartphone adoption along with city-wide sensors to gather live information on a street by street, zone by zone basis. The second is a range of interactive applications that are able to translate data into meaningful alerts for users. The third, inevitably, is mass adoption – common usage by the public, city officials and businesses.

The seamless integration of these three layers can help people travel during quiet periods, choose the most efficient routes for journeys, consume less energy and water, and reduce stress on public systems.

Studies suggest that, when rolled-out effectively, smart technology has the potential to:

- Streamline mobility. It is estimated that smart cities can cut commuting times by 15-20%, or as much as 30 minutes daily in developing cities.[4] Digital signage and mobile apps can be used to transmit information about delays, breakdowns and parking availability.

- Improve health. Apps can help us reduce pollution via mobility and lifestyle efficiencies. They can also remotely monitor chronic conditions, analyze demographic susceptibility and improve targeted health messaging, by some estimates reducing disability-adjusted life years (DALY) by 8%-15%.

- Increase public safety. Real-time crime mapping, data-driven policing, smart surveillance and efficient emergency vehicle routing can cut fatalities by 8%-10% and crime by 30%-40%, offering substantial peace-of-mind benefits.

- Rescue the environment. Automated building systems, congestion-quashing apps and dynamic electricity pricing have the potential to reduce harmful emissions by 10%-15%. Air quality sensors can identify the sources of pollution, while monitors for water consumption and wastage can cut the amount of water needed. In terms of recycling, pay-as-you-throw tracking can reduce waste by 30-130 kilograms per person annually.

Reimagining cities for a driverless future

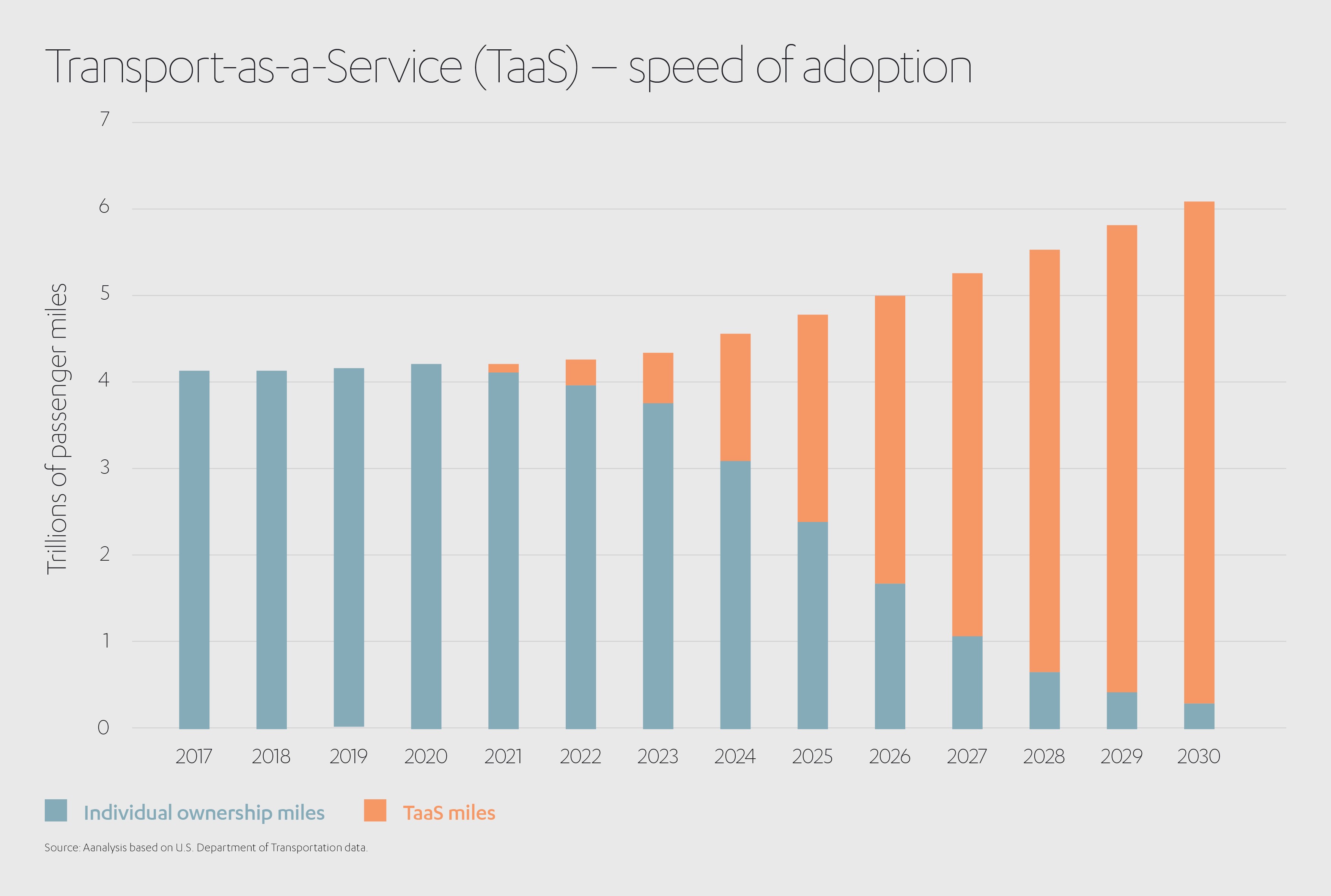

The impact of autonomous cars is nothing short of a revolution-in-waiting. Independent technology think-tank RethinkX argues that within a decade of regulatory approval for driverless vehicles, some 95% of passenger miles traveled in the US will be via autonomous EV (electric vehicles).

The impact of autonomous cars is nothing short of a revolution-in-waiting. Independent technology think-tank RethinkX argues that within a decade of regulatory approval for driverless vehicles, some 95% of passenger miles traveled in the US will be via autonomous EV (electric vehicles).

Companies operating driverless vehicles will account for around 60% of the US vehicle stock, and the number of passenger vehicles on American roads will fall from 247 million to 44 million between now and 2030[5].

As our streets become less car-focused and more people-focused, the urban landscape will undergo a makeover.

A typical city street currently devotes anywhere from 60%-90% of its space for vehicles, with pedestrians squeezed into the leftover area.[6]

However, fewer vehicles equate to less parking, with one report by the OECD’s International Transport Forum (ITF) suggesting the average vehicle’s idle time will drop from 95% to 5%[7].

However, fewer vehicles equate to less parking, with one report by the OECD’s International Transport Forum (ITF) suggesting the average vehicle’s idle time will drop from 95% to 5%[7].

Indeed, by 2050 driverless cars could cut the need for parking in the US alone by some 5.7 billion square miles[8].

Could streets of the future, therefore, become places that “transform the first 30 feet of space extending from buildings into an activity-filled, indoor/outdoor public realm?”[9] Some architects and urban planners believe so.

Virtuous cycle eclipses the vicious circle

Crucially, redesigning our cities also makes sound financial sense. And when money talks, decision-makers have a habit of listening.

Analysts calculate that smart cities will create growth opportunities worth US$ 2.46 trillion by 2025[10]. This means that improvements should unfold exponentially. Cities prioritizing digitalized services and data analytics will find that spending on technology increases rapidly once the process is under way.

With such enticing data readily available, the current drift towards smart cities should come as little surprise. That said, it is of course governments that will ultimately dictate the reshaping of our cities in the 21st Century.

The European Commission (EC) coordinates an innovation partnership for smart cities and communities (EIP-SCC), uniting cities, industries, small businesses, banks and researchers in the goal of better urban living.

The European Commission (EC) coordinates an innovation partnership for smart cities and communities (EIP-SCC), uniting cities, industries, small businesses, banks and researchers in the goal of better urban living.

Its focus includes sustainable mobility and buildings, knowledge-sharing, policy and planning, as well as integrated infrastructures for energy, information, technology and transport. In a sign of its ongoing success and the European Commission’s faith in the project, the EIP-SCC is soon to merge with the Smart Cities Information System (SCIS) data exchange and be repositioned as an all-encompassing Smart Cities Marketplace.

“The Smart Cities Marketplace will help cities and towns of all sizes to deliver more sustainable urban energy systems. It offers all the information needed to explore, shape and set up a successful smart city project in one place,” explains Georg Houben, EC policy officer.[11]

The EC is far from alone. Globally, evidence is mounting that forward-thinking governments are eclipsing their rivals when it comes to designing cities fit for the future.

Policies pivotal to transforming cityscapes

Copenhagen in Denmark was an early trendsetter in transformative policies, outlawing traffic from its medieval main street Strøget in 1962. The pedestrianization project continued over the following decades, and today Copenhagen has some 96,000 square meters (33% street, 67% public squares) of car-free space.[12] The city authority has devised a special traffic management strategy by limiting parking spaces, reducing the number of lanes on main routes into the city centre, restricting through-traffic, and developing train, bus and cycle networks. Now, it is estimated that some 80% of all journeys in Copenhagen are made on foot and 14% by bicycle. Commercially the project speaks for itself, with ‘stop and stay’ activities in Copenhagen almost four times greater than in the 1960s.

Elsewhere, innovative thinking flourishes. In China, high-rise Shanghai has embarked on a novel new direction – underground construction. The Shanghai Natural History Museum, located in a park near the financial district, has been built downwards into the earth. It features glass walls to permit natural lighting via the sun’s rays, and eco-friendly cooling courtesy of a courtyard pool.

Los Angeles has retrofitted more than 7,000 kilometers of sodium-vapor streetlights with greener LEDs. The LEDs aren’t just efficient – they’re also intelligent, communicating performance and breakdown issues directly to city headquarters. In the future their brightness could be adjustable to respond instantly to incidents and events.

In the Netherlands, planners in Eindhoven devised a unique plan to overcome the city’s notoriously busy intersections, which had long acted as a deterrent to cyclists. The result in 2012 was the US$ 8 million Hovenring, a 1,000-ton steel elevated flyover for bicycles. The roads beneath were lowered to ensure those ascending the Hovenring face a gentle gradient.

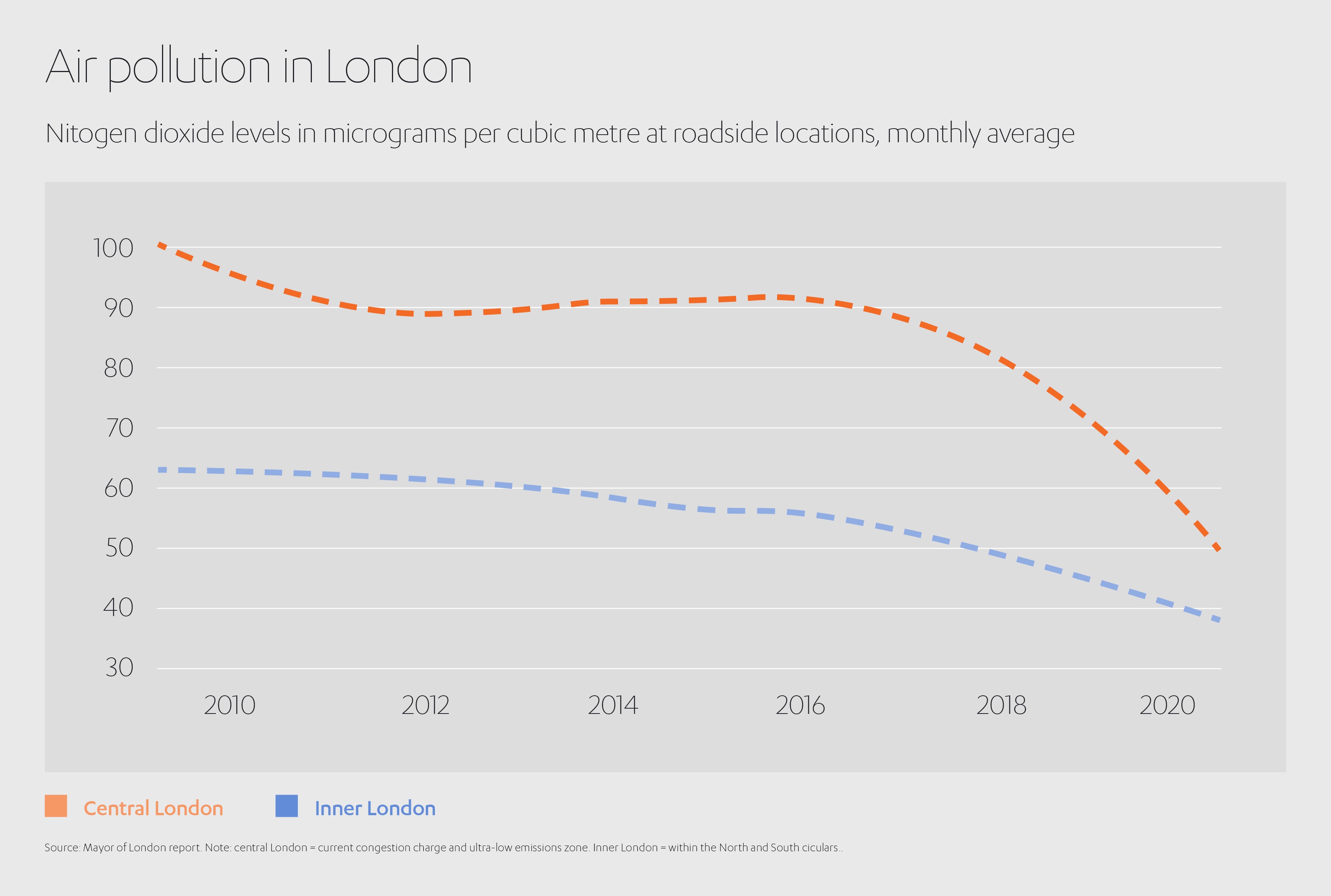

In London, meanwhile, a recent report shows the number of people exposed to illegal pollution levels has plummeted by 94% since 2016.[13] The report suggests between early 2017, and early 2020, levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) alongside roads in central London fell by 44%.

In London, meanwhile, a recent report shows the number of people exposed to illegal pollution levels has plummeted by 94% since 2016.[13] The report suggests between early 2017, and early 2020, levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) alongside roads in central London fell by 44%.

A range of policies are credited with triggering this decline: charges for dirty vehicles entering the city, the introduction of low-emission buses, new laws forbidding diesel taxis, and extra protection for cycle spaces.

Further north in the UK, planners in the city of York have unveiled a scheme to build the UK’s largest zero-carbon housing project, with 600 homes across eight sites within the ring-road zone. The estates will have trees and allotments – but no cars. Each house will have solar panels, cycle sheds, electric charging points, and access to a fleet of rental cargo bikes. If the scheme proves popular it could be used as a template for similar schemes elsewhere across the UK.

Dubai is also showcasing its own vision for the city of the future, with the Sustainable City, the first net zero energy development in the emirate. The 46-hectare community of 500 villas and 89 apartments incudes EV charging points, 11 natural ‘biodome’ greenhouses, organic farm and individual garden farms that use a passive cooling method with fans and pads, solar panels on all houses, UV reflective paint to reduce the thermal heat gain inside the houses and waste water recycling, with segregated drainage for greywater and blackwater using papyrus as a biofilter.

Technological readiness and public enthusiasm for such progressive projects vary around the world. Taking the notion of ‘smart cities’ as its cue, McKinsey has assessed the current smart status of 50 major urban centers globally.[14]

Amsterdam, New York, Seoul, Singapore, and Stockholm all rank highly in terms of sensor installation and communication networks – but even these pioneers are judged to be only two-thirds of the way toward a sufficiently-sophisticated tech base. Broadly, cities across Europe, North America, China, East Asia and selected Middle East territories have strong tech bases, while those in India, Africa and Latin America have much catching up to do, particularly in costly sensor installation work.

A rather different picture emerges when assessing public awareness and acceptance of smart concepts. Here, Asian cities outperform all others for usage and satisfaction levels, while European cities show more resistance.

“Positive adoption and awareness appear correlated with having a young population that not only accepts a more digital way of doing things but also expects it,”[15] the McKinsey report notes.

Decisions which shape the future of our cities deserve forensic levels of consideration, because the price of failure is high.

One need only look at Skopje, the capital city of North Macedonia in southeastern Europe, often cited as the continent’s most polluted capital. In 2018, levels of pollutant particles in Skopje surpassed EU limits on 202 days of the year. The problem, caused by an over-reliance on burning wood for domestic heating, dirty outdated vehicles on the roads and limited public transport, is estimated to be responsible for 4,000 premature deaths in Skopje annually.[16]

Or take the case of Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, where widespread poverty and poor urban design has led to regular flooding, overflowing sewers and rampant disease. With more than 44,500 people per square kilometer, Dhaka is the world’s most crowded city[17]. Some 40% of inhabitants are classed as slum-dwellers and population numbers far outstrip healthcare resources.

How harsh these realities feel contrasted with the utopias envisioned by architects and urban planners when their imaginations are given free rein: landscapes of urban farms and sky gardens, drone commuting and restored wetlands and solar buildings . . .

It is clear that cities, if not carefully developed and managed, are focal points for both social and environmental dilemmas. And yet they are destined to remain the powerhouses of our civilization for the foreseeable future.

Pandemic prompts city-scale creative thinking

The recent pandemic has highlighted how we must adapt our way of life to make cities healthier and fairer places in the future.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) says the world is currently confronting “the ineptitude of existing health and wellbeing infrastructure and the consequences of inadequate preventative health mechanisms, particularly for the most vulnerable in society”.[18]

Inequality lies at the heart of much of the suffering during the pandemic, notes the WEF, with urban lifestyles blighted by over-reliance on vehicles, unhealthy diets and poor environmental conditions. These factors are not new, however, and are replicated in developing economies such as India, where by 2030 a rise in non-communicable diseases could account for 70% of the country’s illnesses.[19]

If the pandemic serves any beneficial purpose it is focusing our attention on the dual problems affecting many of our cities – inequality and health. Depending on the pressures and resources facing different regions globally, the WEF suggests that mitigation strategies should involve[20]:

- Improved sanitation systems

- More pedestrian routes to encourage physical activity

- Personalized diagnostics for healthy lifestyles

- Vertically-farmed fruit and vegetables for more nutritious, locally-sourced diets

- Local interventions such as mobile public showers

- Universal income policies to ensure basic living standards

Such measures won’t come cheaply or be logistically simple. They will require the cooperation of national and local governments, private developers, investors and multilateral organizations.

The developing world might come to rely upon initiatives such as multilateral development finance institutions (MDFIs), with the African and Asian Development Banks being prime examples. These groups have the influence necessary to unite heads of state and private sector leaders behind ambitious recovery plans, together corralling funds for long-term urban infrastructure development strategies.

Better cities for better lives

Cities are nothing without the people who inhabit them. I am humbled and honored to be in a position to contribute to solutions to support new ways living, working and powering our future, commercially through Abdul Latif Jameel – as an investor in the infrastructure of life – and through Community Jameel, my family’s global philanthropy.

We all have the right to a healthy life, so in 2018, Community Jameel co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health (Jameel Clinic) at MIT, which conducts vital research in machine learning, biology, chemistry and clinical sciences. The Jameel Clinic complements the work of our other labs, including the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics (Jameel Institute) at Imperial College, London, where AI data analytics helps identify and prevent communicable diseases and public health threats worldwide, and the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems lab (J-WAFS), which fuels research, innovation and collaboration to tackle urgent global water and food systems challenges – issues which will need to be at the heart of any truly sustainable city.

In 2020, we formalized our commitment to improving global healthcare by establishing Abdul Latif Jameel Health, to accelerate access to modern medical care while addressing unmet medical needs in developing markets around the world. This builds on our existing partnerships with health tech companies around the globe to improve healthcare accessibility, such as Japanese companies Cyberdyne and Cellspect.

We are equally passionate about building on our legacy as prime movers in eco-friendly transport solutions to envisage what city-scale mobility will encompass in the coming decades.

We played a key role in a pilot project for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Saudi Arabia, supplying a test fleet of Toyota Mirai hydrogen-powered vehicles. We are also early stage investors in RIVIAN, the US-based EV innovator, and we have invested in California’s air-taxi pioneer Joby Aviation, helping it to become the world’s best funded air-taxi start-up.

One of the biggest challenges, of course, will be generating clean energy to power our cities. That’s why, in 2015, we acquired renewable energy specialist Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV), which is now active in 18 countries across a range of solar and wind power projects.

Similarly, our groundbreaking Almar Water Solutions enterprise aims to address the water needs of our growing population, with landmark projects in Mombasa, Kenya; Al Shuqaiq in Saudi Arabia; and Muharraq in Bahrain. Most recently, Almar expanded its portfolio again with the acquisition of the Ridgewood Group in Egypt, with 58 desalination plants across the country.

Investing to drive change

These investments – and many others like them – demonstrate our commitment to investing in businesses and technologies that deliver a return based as much on environmental, social or governance performance, as on financial results. It also reflects a growing global interest in so-called ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investing, (also often referred to as ‘sustainable investing’) which could pay dividends for the development of new technologies and ideas that could help to redesign our cities.

Research by PwC predicts that ESG investment funds could increase their share of the European fund sector from 15% to 57%[21] by 2025. This could have big implications for companies by redirecting capital into sustainable activities and forcing businesses to be transparent about everything from their environmental impact to their treatment of employees.

It is not only about changing institutional investing patterns, however. I believe that private businesses – like Abdul Latif Jameel – can be key catalysts in driving both business and government investment into solutions to combat climate change and accelerate the transition to a more sustainable economy and more successful cities. Organizations like the Clean, Renewable and Environmental Opportunities Syndicate (CREO Syndicate), of which Abdul Latif Jameel is a member, are already helping to change attitudes and explore private investment opportunities across the global ESG marketplace.

These are the kinds of bold initiatives that can enable our cities to remain hubs of industry and culture for generations to come.

But if as a civilization we fail to act?

Already, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, there is evidence of people drifting away from cities to less crowded areas, in search of safer and more sustainable lifestyles[22]. Consequently, if we want cities to reassert themselves as economic catalysts, we may have to broaden our imaginations and alter our priorities.

We might even want to take inspiration from Bhutan, Asia, where policymakers are increasingly guided by a Gross National Happiness Index.[23] Or we might perhaps follow the example of forward-thinking countries such as Iceland and New Zealand, increasingly adhering to recommendations of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance.[24]

Above all, when redesigning our cities for the 21st Century and beyond, we should remember that cities should exist in the service of people – and not be lulled into falsely believing the reverse.

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/02/10-cities-are-predicted-to-gain-megacity-status-by-2030/

[2] https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

[3] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/smart-cities-digital-solutions-for-a-more-livable-future

[4] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/smart-cities-digital-solutions-for-a-more-livable-future

[5] https://www.rethinkx.com/press-release/2017/5/3/new-report-due-to-major-transportation-disruption-95-of-us-car-miles-will-be-traveled-in-self-driving-electric-shared-vehicles-by-2030#:~:text=95%20percent%20of%20U.S.%20passenger,as%20a%20Service%20(TaaS).&text=As%20fewer%20cars%20travel%20more,to%2044%20million%20in%202030.

[6] https://www.hok.com/ideas/research/autonomous-vehicles-urban-planning/

[7] https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/Panorama/Articles/Should-we-try-to-make-parking-spaces-extinct

[8] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/ten-ways-autonomous-driving-could-redefine-the-automotive-world

[9] https://www.hok.com/ideas/research/autonomous-vehicles-urban-planning/

[10] https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/news/smart-cities-predicted-to-create-growth-opportunities-worth-246-trillion-by-2025-5714

[11] https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/news/news/european-commission-launches-smart-cities-marketplace-5720

[12] https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pubs/pdf/streets_people.pdf

[13] https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/air_quality_in_london_2016-2020_october2020final.pdf

[14] mckinsey.com/smartcities

[15] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/smart-cities-digital-solutions-for-a-more-livable-future

[16] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200701-skopje-north-macedonia-the-most-polluted-city-in-europe

[17] https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/mar/21/people-pouring-dhaka-bursting-sewers-overpopulation-bangladesh

[18] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/08/healthy-cities-communities-post-covid19-great-reset-healthcare-disease-risk/

[19] http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Consumption_Fast-Growth_Consumers_markets_India_report_2019.pdf

[20] http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Consumption_Fast-Growth_Consumers_markets_India_report_2019.pdf

[21] https://www.pwc.lu/en/sustainable-finance/docs/pwc-esg-report-the-growth-opportunity-of-the-century.pdf

[22] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/oct/03/green-and-pleasant-beats-urban-buzz-as-families-opt-to-leave-cities?

[23] http://www.gnhcentrebhutan.org/what-is-gnh/gnh-happiness-index/

[24] https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wego

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit