Order from chaos: can we de-risk our precarious planet?

In an increasingly unpredictable world, one rocked by conflict, paralyzed by epidemics and stalked by the violent symptoms of climate change, a comprehensive understanding of risk is a valuable torch in the darkness. Grasping the reality of risk empowers families to plan their lives, business leaders to keep our industries thriving, and governments to build stronger societies. Continuing to ignore risk, because it is either overwhelming or unpalatable, means continuing our spiral into self-destruction.

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) 18th annual Global Risks Report aims to salvage some order from this chaos. Its 2023 instalment is quick to set out the scale of the crises facing our modern world, anchored in what it describes as “a particularly disruptive period in human history”.[1]

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) 18th annual Global Risks Report aims to salvage some order from this chaos. Its 2023 instalment is quick to set out the scale of the crises facing our modern world, anchored in what it describes as “a particularly disruptive period in human history”.[1]

The WEF portrays a near future blighted by low economic growth, reduced international cooperation, and a series of compromises damaging to both climate action and societal development.

The global risk profile of 2023 is a complicated mix of the familiar and the new.

Age-old challenges – inflation, trade wars, social unrest, and geopolitical confrontation – are charging head-on into new upheavals unique to our modern era: unsustainable debt, deglobalization, declining living standards, and a vanishing window for limiting global warming to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels.

This perfect storm of challenges heralds, in the words of the WEF, the start of a “unique, uncertain and turbulent” phase of human history. A positioning also acknowledged in the business world with the rising use of the acronym ‘VUCA’ – volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity – a phrase originally coined 1987, based on the leadership theories of Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus, to describe today’s global commercial and policy environment.

Based on surveys with experts in the field, the WEF report examines both short-term risks (those we will confront by the mid-2020s) and longer-term risks (those coming to the forefront in approximately a decade’s time).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, our greatest two-year challenges exhibit an economic bias, while our longer-term challenges are more existential in nature.

Mitigating these longer-term challenges, which threaten to undermine our entire way of life, will require unprecedented upheavals to our systems and structures. But before we can begin tackling their causes and redesigning our world, we must first face down the crippling cost-of-living crisis, considered the most incendiary threat to global stability over the next two years.

Economy serves as bellwether of future risk

Economic pressures are likely to heighten between now and 2025 due to three factors: the Russia/Ukraine situation, keeping fuel prices high; the continued shortage of components in the aftermath of pandemic shutdowns; and trade wars affecting international supply chains.

The numbers suggest cause for concern. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts global growth will fall to 2.9% in 2023, well down on the historical average of 3.8%.[2] The US economy may enter recession later this year, or at best expand by a slender 0.5% – 1%, a sharp decline from the 1.5% – 2% growth of 2022 and the 6% growth achieved in 2021.[3] Property values, often a barometer of public confidence, are also ringing alarm bells. House prices in the UK could fall by around 8% in 2023, the second steepest annual decline in 70 years.[4]

Perils abound. Mismanaged fiscal policies, say the WEF, risk liquidity shocks and society-wide debt distress. An emerging scenario of stagflation (ongoing high inflation combined with a stagnant economy) could exacerbate historically high levels of public debt and trigger profound socioeconomic aftershocks.

As is so often the case, it is the most vulnerable sections of society that are set to suffer most under this economic realignment.

The UN’s latest State of Food Security and Nutrition report shows some 821 million people experiencing hunger in 2021, up 46 million from a year earlier. Hunger now affects almost 10% of the world population, a sharp rise from 8% as recently as 2019, representing a rapid reversal in efforts to eliminate global malnutrition.[5]

The UN’s latest State of Food Security and Nutrition report shows some 821 million people experiencing hunger in 2021, up 46 million from a year earlier. Hunger now affects almost 10% of the world population, a sharp rise from 8% as recently as 2019, representing a rapid reversal in efforts to eliminate global malnutrition.[5]

Soaring poverty and the specter of hunger have the latent potential to spur unrest within more fragile nations of the developing world, ranging from street protests to state collapse.

As the pieces settle and a new economic reality comes into focus, the WEF warns of an era of “growing divergence between rich and poor countries and the first rollback in human development in decades”.[6]

Forecasters anticipate a period of ‘geoeconomic weaponization’. As domestic pressures escalate, nations are expected to tighten fiscal policies to increase their sovereignty and limit the growth of rivals – though all this might achieve is to reaffirm the interdependence of the modern global economy.

Even as we face a storm of economic challenges, further financial pressures beckon. Several of the world’s economic lynchpins are also among those most prone to inter-state tensions. Any spillover from economic warfare to actual warfare could slam the brakes on a worldwide economic recovery.

Still, the world has endured seemingly insurmountable economic crises many times before and emerged stronger and fitter. See the Great Depression of 1929 – 1939, the OPEC Oil Price Shock of 1973, the Asian Crisis of 1997, or the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 – 2008. Conceivably, the same, or a similar thing, might well happen again. As we’ve weathered it before, what’s so different now?

Complicating matters on this occasion are the predicted longer-term hazards identified in the WEF’s new risk report, dominated by the looming environmental crisis.

Climate change: The ‘risk bomb’ that threatens us all

Viewed through a decade-long lens, it is the ecological emergency which seems set to redefine the notion of global risk: a ‘risk bomb’, the fragments of which could extend to every facet of our lives.

Experts consulted by the WEF are unequivocal. Referring back to the above risk lists, seven of the 10 ‘most severe’ dangers by 2033 are directly related to global warming: failure to mitigate climate change, failure of adaptation, natural disasters/extreme weather events, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, widespread involuntary migration, natural resource crises, and large-scale environmental damage incidents. Further, at least two of the remaining top 10 risks are at least tangentially related to climate change – erosion of social cohesion and geoeconomic confrontation.

Hitherto slow progress towards the climate goals agreed at COP21 in 2015 – better known as the ‘Paris Agreement’ – has exposed the chasm between rhetorical idealism and political reality. Unfortunately, this means our natural ecosystems will continue to suffer in the medium term as resources and energies are expended on short-term economic difficulties.

Despite repeated pledges to tackle climate breakdown, CO2 emissions have increased 60% since the launch of the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992.[7] Climate change is predicted to cause some 250,000 extra deaths per year between 2030 and 2050, largely from hunger, heat stress and disease.[8]

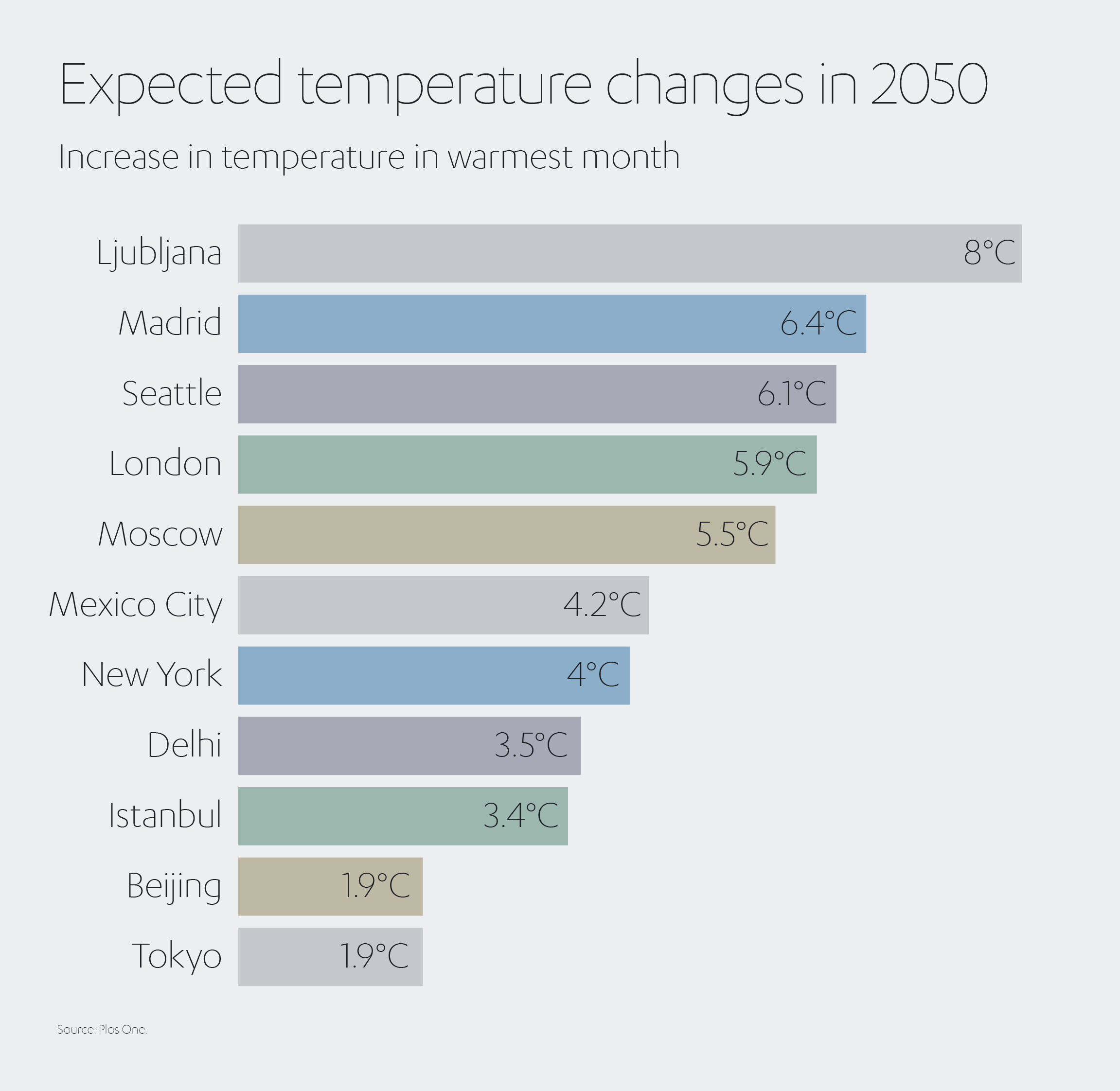

By 2050, cities across several continents – Asia, North America and Europe – are expected to see ‘warmest month’ temperature rises of between 1.9°C and 8°C.[9] By that same date, sea levels along the United States’ coastline could rise as much as 12 inches (30.48cm) above today’s waterline.[10]

In the absence of coordinated policies, or massive investment in green industries, climate change impacts could spiral. Natural resource depletion, biodiversity loss and food shortages could conspire to cause accelerated ecosystem collapse, and far more devastating natural disasters.

Biodiversity loss / ecosystem collapse, not deemed a top 10 risk within the next two years, catapults up the risk agenda to fourth place by 2033. With biodiversity already declining faster than at any previous point in human history, the fear is that nature will pass an invisible point of no return.[11]

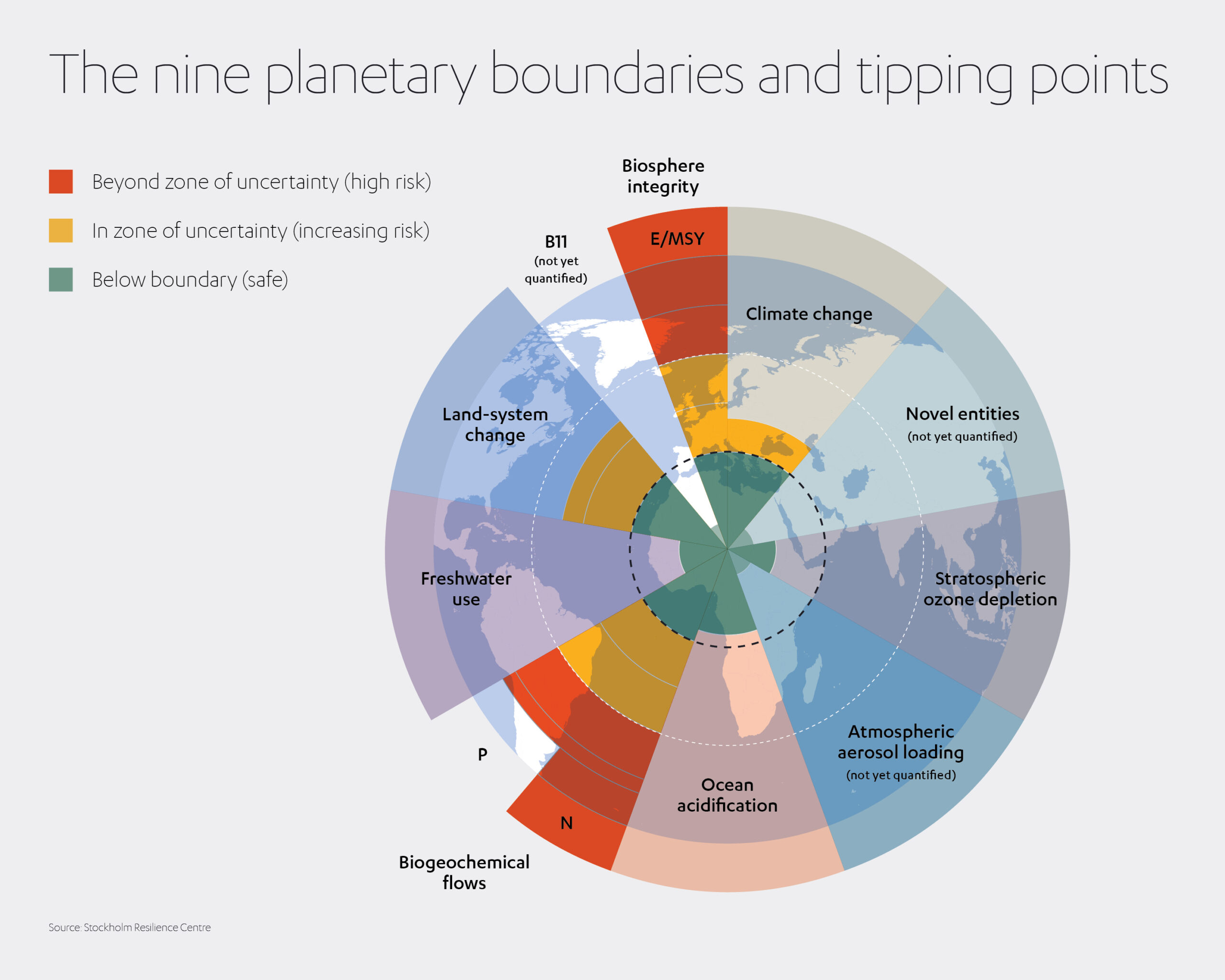

The loss of biosphere integrity is one of nine ‘planetary boundaries’, or tipping points, developed in 2009 by Swedish scientist Johan Rockström. In its landmark research, Rockström’s team identified nine key processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth, within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive. Crossing one or more of these boundaries, however, risks causing large-scale and irreversible environmental damage.[12]

With more than half the global economy at least partly dependent on nature or natural resources, ecosystem collapse will lead to falling harvests, the nutritional decline of crops, a widespread failure of pollination, and ever-more damaging floods and wildfires. All ecosystems will be affected, from Arctic ice plains, to coral reefs, to forests and seagrass biomes. There is no refuge from risks of this magnitude.

Worse, mitigation strategies for competing climate crises sometimes pull in different directions and simply shift the burden from one dilemma to another. High-intensity farming, for instance, pivotal for solving world hunger, can collide head-on with land conservation strategies. Even renewable energy infrastructure can have unintended consequences such as habitat loss, noise pollution and interference with migration patterns.

We must also confront the unfortunate dovetailing of ‘risk severity’ with ‘preparedness’ – or rather, lack thereof. Of the 10 global risks for which the WEF report says we are least prepared, more than half are climate-related. Only around 10% of survey respondents believe our climate change mitigation preparedness is effective or better, with some 70% regarding our readiness as ineffective or worse.[13] Similar pessimism surrounds our perceived level of preparedness for biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and natural resource crises.

Ultimately, when we think about risk, about global warming, about food chains and biodiversity, what we are actually contemplating is the human experience – our quality of life and our ability to survive as a species.

So, as we navigate our new network of risks, what are the prospects for human health?

Climate change risks state of ‘perma-pandemic’

If we ever needed a reminder about the fragility of the human body, COVID-19 provided that wake-up call. One global shutdown, 5 million+ deaths and a US$ 12.5 trillion economic toll later, and mankind’s subservience to the ecosystem has been firmly (re)established – if that were ever truly in doubt![14]

Beyond its headline impacts, the pandemic also brought belated attention to broader health challenges such as antimicrobial resistance (associated with almost 5 million deaths in 2019[15]) vaccine hesitancy and climate-driven diseases.

Climate change will affect all flora and fauna; in our susceptibility, we humans are little different to any of our fellow animals.

Failure to mitigate climate change (deemed the number one risk by severity over a 10-year timeframe) will trigger a cascade of health-related impacts for humanity. These include rising air pollution, an increase in waterborne contaminants, and more deadly ‘wet blub’ events (days when the combination of heat and humidity hamper the body’s ability to cool itself down). Global warming will also lengthen the ‘danger season’ for existing diseases spread by insects, such as malaria (2021 fatalities: 619,000[16]) and dengue fever.

Ongoing urbanization decreases natural habitats and brings humans into ever-closer contact with wild animals. This threatens an unrelenting rise in zoonotic diseases such as SARS, MERS and avian flu, and a situation ominously described by the WEF as a ‘perma-pandemic’.

Health systems are scarcely able to keep pace with existing challenges, let alone prepare for the unknown. In the UK in 2022, for instance, around 7 million people were stuck waiting for non-urgent medical treatment, even as one-in-ten National Health Service jobs went unfilled. The World Health Organization (WHO) is predicting a shortfall of some 10 million health workers worldwide by 2030, mostly in low and lower-middle income countries.[17]

Government cuts to medical spending could have a dangerous effect on human health, and such scenarios are plausible even in the developed world. The US already spends some 20% of its GDP on healthcare, even though its largest population demographic is still yet to retire.[18]

We might imagine that technology will blossom into our salvation. But caution is advisable, because technology brings a risk of its own: the risk of widening inequality.

Countries with developed economies and deep pockets are set to monopolize rewards from advances in AI, quantum computing and biotechnology in the coming years. Unless they can maneuver out of the slow lane, emerging economies face missing out on this tech-driven turbocharge, along with associated improvements in healthcare, climate mitigation and agriculture.

Even countries at the forefront of the technological revolution cannot afford complacency. Inevitably, our increasing dependence on technology will usher in new perils to counter – from invasions of privacy to online crime, to cyberterrorism.

And yet . . . even in the context of a risk analysis, there remain oases of hope.

The WEF outlines several ways we, within the silos of our nations and societies, can change our behavior and help offset some of the risks heading our way.

A technological lifeline: Curing the causes of risk

First and foremost, as Fady Jameel, Abdul Latif Jameel Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel, has previously discussed in previous articles like this one, we must not allow our immediate economic woes to jeopardize our long-term goal of combating climate change – by far the deadliest risk waiting in our collective future.

While the cost-of-living crisis leads the two-year list of risks facing humanity, most experts perceive it as a temporary hazard; in the 10-year risk list, cost-of-living vanishes entirely from the top 10 list of concerns. From this decade-long perspective, counteracting global warming is deemed fundamental to neutralizing other high-ranking risks, such as ecosystem collapse and large-scale involuntary migration.

Keeping global warming to no more than 1.5°C means, according to the UN, reducing emissions by 45% by 2030 and hitting net zero by 2050.[19] A transformation is needed within the energy sector, responsible for around three-quarters of all such emissions.

We must rapidly replace polluting coal, gas and oil-fired power stations with wind or solar farms. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates around 88% of energy could be green by 2050, encompassing a mix of wind, solar, hydro, bioenergy and geothermal plants.[20]

Swift action makes not just environmental sense but also economic sense.

Apart from de-risking our planet, research shows decarbonizing our energy systems will save the world at least US$ 12 trillion by 2050.[21]

The march of technology, despite our wariness, yields many benefits. Modern wind turbines are taller than ever and capture more potential energy from higher air currents. The average capacity of new wind turbines in the US during 2021 was 3 MW, up 9% from 2020 and a huge 319%from 1998/1999.[22] [23]

It is the same story for solar power. Advances in photovoltaic technology mean modern high-efficiency solar panels can reach 23% efficiency, far outpacing the 15% efficiency benchmark of earlier systems.[24]

Technology is also driving the current surge in the global vertical farming sector, tipped to achieve a CAGR of 26% by 2033 and hit a US$ 34 billion turnover. Such cutting-edge agricultural techniques boost food output per square meter, with less water use and fewer chemicals.[25]

If technology can help spare us from the dire risks of climate change, we can begin contemplating how to save humanity from our worst enemy. Ourselves.

Four steps to a less risky future…

Tackling the risks to come will not be a piecemeal effort conducted on a country-by-country basis – not if it is to be successful. Political leaders need to work together, across borders and across continents, designing joined-up solutions to the risks uniting us all.

“Defensive, fragmented and crisis-oriented approaches are short-sighted and often perpetuate vicious cycles,” argues the WEF. Instead, it calls for a “rigorous approach to foresight and preparedness”, aiming to “bolster our resilience to longer-term risks and chart a path forward to a more prosperous world”.[26]

The WEF has proposed a four-step manifesto to improve our global response to risk:

- Getting better at spotting risks ahead of time: ‘Horizon scanning’ and ‘scenario planning’ are cited as useful strategies for extrapolating subtle indicators in data. Together, they could help us anticipate and prepare for future macro-scale events such as temperature rises, border strife and emerging pandemics.

- Redefining what ‘future’ means: Too much public policy is dictated by recent catastrophes; similarly, too many boardroom decisions are based on averting immediate threats. Institutions, public and private sector alike, must work harder to separate risk prioritization from shorter-term motivations.

- Keeping an eye on the bigger picture: Policymakers must remember that many crises are related. Consider how both climate change and armed conflict could impact food supply chains and hunger. So, addressing risk will often require cross-sector preparedness. Sometimes one intervention has multiple pay-offs, such as investment in education simultaneously benefiting GDP, healthcare and living standards.

- Sharing a common vision: Truly impactful interventions usually come from a broad cross-section of society: governments, NGOs and the private sector. Open sharing of data between nations has already helped save lives across a range of risks, from natural disasters to terror attacks. Such collaborations are a template for the future.

There are reasons to avoid a defeatist attitude. While volatility increases the likelihood of risk events, stability has the opposite effect – and the expert insights in the WEF report foresee less volatility in a decade’s time than we are experiencing presently.

Two years from now, 82% of respondents expect us to be existing in a state of ‘persistent crises’ or ‘consistent volatility’. However, by 2033 this figure has fallen to 54%, with the remainder anticipating occasional localized surprises, relative stability, or even a revival of global resilience.

… and four destinies to choose between

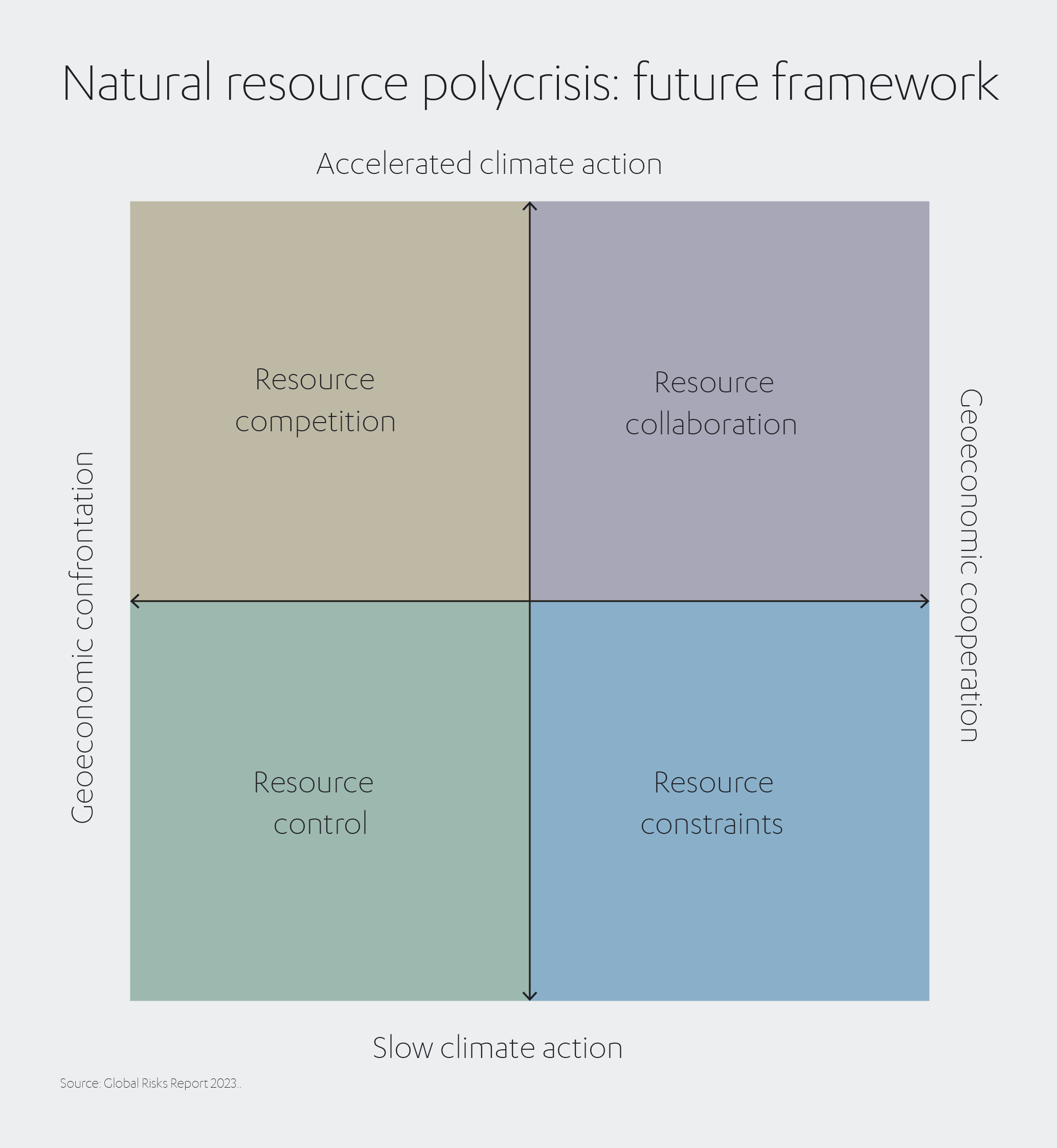

Our priority, says the WEF, is to avoid stumbling blindly into a ‘polycrisis’ – multiple crises clustered around natural resource shortages by 2030. A polycrisis represents a network of interconnected risks converging to create problems greater than the sum of their parts.

The best defense against an insidious polycrisis is an awareness of how related environmental, geopolitical and socioeconomic risks might lead to greater competition for life’s essentials: food, water, fuel and energy.

Adopting a long-term, international mindset will empower us to choose between four starkly different future scenarios.

- Resource collaboration: Nations work together to curtail the worst impacts of climate change and maintain a global food supply chain. Shortages of water, metals and minerals are unavoidable yet manageable, leading to a limited humanitarian crisis in poorer regions.

- Resource constraints: Competing global crises hinder climate change action, leading to hunger and energy shortages in vulnerable countries. Significant humanitarian crises develop, compounded by political instability.

- Resource competition: International rivalry and distrust causes an insular self-sufficiency drive in richer countries, leading to a wider rich/poor divide globally. While food and water needs can be met domestically, lack of critical minerals and metals in the developed world results in shortages, price wars and the emergence of new power blocs, with the growing danger of accidental conflict breaking out.

- Resource control: Geopolitical friction exacerbates climate-driven food and water shortages, leading to a truly global multi-resource crisis, with widespread socioeconomic impacts of unprecedented severity, famine and drought refugees, and frequent clashes between states.

Clearly, collaboration is the optimum approach, and the private sector is uniquely placed to help steer society towards this least risky scenario.

Private sector’s role in risk reduction

At Abdul Latif Jameel, we are using the power of our private capital to help reduce global risk by combating climate change and promoting a green recovery, in line with the UN Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Our flagship renewable energy business, Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV), is endeavoring to ensure affordable clean energy for all. FRV manages a growing portfolio of solar, wind, energy storage and hybrid energy projects throughout the Middle East, Australia, Europe and Latin America.

FRV’s innovation arm, FRV-X, is pioneering utility-scale battery storage plants (BESS), among other cutting-edge energy technologies, to ensure round-the-clock power supplies to our homes and communities. It is already involved in BESS projects in the UK at Holes Bay, Dorset; Contego, West Sussex; and Clay Tye, Essex; plus a hybrid solar and BESS plant a Dalby, Queensland in Australia. FRV acquired two additional BESS projects in the UK in autumn 2022, as well as a majority stake in a BESS project in Greece.

FRV-X has also recently invested US$ 10.6 million in ecoligo, a German-based impact-led ‘solar-as-a-service’ provider. Founded in 2016, ecoligo takes a ‘bottom-up’ approach to developing solar energy generation, working directly with commercial and industrial customers in emerging markets to develop solar power projects to meet their energy needs. Each project is financed by individual investors via an innovative crowdinvesting platform. ecoligo currently operates in 11 countries, including Kenya, Ghana, Costa Rica, Vietnam, the Philippines and Chile.

How else are we helping to de-risk a future of dangerously depleted resources?

Our colleagues at Almar Water Solutions, part of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy and Environmental Services, are showing how advanced technology can help to strengthen the quality and efficiency of water systems. In 2022, it invested with Datakorum, an IoT specialist, to win a contract with e& Enterprise, (previously Etisalat Digital) for a smart-communication project for water and energy infrastructure in Abu Dhabi. The project aims to ensure improved efficiency for customers and contribute to the digitization of local water infrastructure, accelerating operational improvements and preparation of the smart grid.

Meanwhile, the Jameel Water and Food Systems lab at MIT (J-WAFS), co-founded by Community Jameel in 2014, researches techniques for nourishing and sustaining an ever-growing global population, while another Community Jameel/MIT collaboration, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), aims to counter global poverty by advocating for science-led policymaking.

[1] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[2] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO#:~:text=Description%3A%20The%20January%202023%20World,historical%20average%20of%203.8%20percent .

[3] https://www.jpmorgan.com/commercial-banking/insights/economic-trends

[4] https://www.pwc.co.uk/services/economics/insights/uk-key-trends-in-2023.html

[5] https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/un-report-global-hunger-SOFI-2022-FAO/en

[6] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[7] https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

[8] https://www.who.int/health-topics/climate-change#tab=tab_1

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-48947573

[10] https://climate.nasa.gov/news/3232/nasa-study-rising-sea-level-could-exceed-estimates-for-us-coasts/#:~:text=By%202050%2C%20sea%20level%20along,three%20decades%20of%20satellite%20observations

[11] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[12] https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

[13] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[14] https://www.reuters.com/business/imf-sees-cost-covid-pandemic-rising-beyond-125-trillion-estimate-2022-01-20/

[15] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[16] https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022

[17] https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1

[18] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[19] https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition

[20] https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Webinars/07012020_INSIGHTS_webinar_Wind-and-Solar.pdf?la=en&hash=BC60764A90CC2C4D80B374C1D169A47FB59C3F9D

[21] https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/news/decarbonise-energy-to-save-trillions/

[22] https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/eu-wind-installations-up-by-a-third-despite-challenging-year-for-supply-chain/

[23] https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/wind-turbines-bigger-better

[24] https://www.forbes.com/home-improvement/solar/most-efficient-solar-panels/

[25] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

[26] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit