Packaging a problem

The packaging industry is worth more than a trillion dollars per year[1] globally, and with e-commerce extending the supply chain from the extraction of raw materials to the hands of the consumer, it has never been more important to the functioning of the global economy.

But in sustainability terms, packaging is a problem.

Thirty per cent of all waste in industrialized societies comes from packaging alone[2]. This includes all kinds of materials from cardboard and paper, simple and compound plastics, to metals and fabric.

Packaging does undoubtedly serve a number of very valuable purposes. Particularly with food or medical supplies, it is a useful way of extending shelf life and simplifying supply chains. It can increase convenience and usability of a product, such as with perishable items or hygienic wrappings for sterile equipment, like bandages or hypodermic needles.

An attractive and well-designed package gives the consumer a better experience on unboxing their new item. It can also help with educating the consumer through printed instructions included in the box or detachable labels added to parts.

The question is, are the benefits of packaging outweighed by the wastage and resulting environmental impact?

A 21st Century problem?

Before pre-packaged goods became the norm, shops would buy in bulk and wrap up the individual items in paper at the point of sale, with prepackaged goods such as canned foods being the exception.

Self-service supermarkets, starting in the UK in 1948 when the London Co-operative Society opened in London, following the success of Piggly Wiggly in the US where customers had been helping themselves since 1916, required a different style of shopping. The shop assistant could no longer measure out purchases, one customer at a time. Everything that could be packaged, was.

Now almost every shop follows the self-service model, and every manufacturer takes control of their packaging. Glass and paper were superseded by plastic in the 1980s[3] and it is plastic that many consumers think of when they think of problematic packaging. But the true picture is far more complicated.

Plastic’s poor reputation has reduced its use so that now only 19% of packaging waste is plastic-based. This is a similar amount to glass and far less than paper and cardboard, which accounts for more than 40% of discarded packaging by weight.

Despite the fact that all major components of packaging – paper, cardboard, metal, glass, most plastics – can be recycled or composted, less than half of packaging waste is actually recycled in the EU[4], with the rest going to landfill.

The US does a little better, recycling 54%[5] of its packaging waste and using another 9% to generate power through incineration, but it still disposes of more than 30 million tons of packaging waste every year – unsustainably.

So, what’s stopping people and companies from eliminating waste from packaging?

Out of sight, out of mind

For decades, efforts towards sustainability in packaging have generally focused on reduction and recycling. European Union (EU) directive 94/62/EC[6], passed in December 1994 and considered the leading legislation of its time, had a stated aim of reducing landfill waste and plastic pollution. It required designers and manufacturers to minimize the amount of packaging used, phase out certain toxic pollutants and aim for recyclability wherever packaging was unavoidable.

This approach has helped avoid a gigantic amount of waste in the nearly 30 years since it was introduced, but it will never completely eliminate it. Even if packaging companies do the very best job they can, there will always be some wastage if the aim is only to reduce, rather than eliminate.

For decades, the general principle for managing packaging waste was ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ What that tended to mean was that authorities in Europe and North America paid other people to deal with their waste – most notably in China and the Far East. But in 2017, the Chinese Government passed a law[7] preventing ports in China from accepting 24 different types of waste intended for recycling. These included unsorted paper and polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a type of plastic commonly used for disposable bottles. The millions of tons of imported waste had been piling up, unrecycled, dirty and causing a major health hazard, as it was uneconomic to process much of it back into raw materials.

This prompted a nationwide campaign against what people referred to as ‘yang laji’ – ‘foreign rubbish’ – and on the January 1, 2018, the imports stopped. Even though some types of waste were theoretically not banned, the hygiene standards required were so high the ports were unable to process shipments. At the same time, the countries of origin were often unable to take them back because their own recycling industry, unable to compete against what had been a cut-price Chinese option, had either disappeared completely or no longer had the facilities to cope.

Countries in South-East Asia still accept some of the waste that used to go to China, including Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand, but they do not have the capacity to deal with it on the same scale[8]. Even now, these countries do not have the facilities to recycle certain types of low-grade wastes and they are burned or go to landfill.

Finances of recycling

Some types of waste, such as aluminum cans or cardboard, are valuable enough to make recycling facilities economically viable, and widespread collection regimes in many countries mean that this is done very successfully.

The cardboard recycling rate in the US is 91%[9], for example. For many other types of packaging that we throw away, however, the recycling process is too expensive and the resultant raw materials not sufficiently valuable for this to be successful. This is especially the case for composite packaging composed of layered materials that are incompatible when it comes to the recycling process, such as juice cartons that combine card and a plastic waterproofing layer.

There are two main reasons why recycling can be economically unviable: energy costs and complexity of source materials.

An aluminum recycler has a simple equation to make a profit: the cost of the energy used in the recycling process must be less than the value of the material recovered. Waste aluminum is often easily collected in a largely pure form – as food containers, for example – so the recycling process is straightforward as long as energy prices do not rise too high; a factor that can be made more affordable through the use of lower-cost renewable energy, such as self-generated solar power.

On the other hand, a company that recycles the gallium in mobile phones or the cobalt in electric vehicle batteries, for example, faces a complex technical challenge to isolate their target components before they can begin the purification process that results in a saleable commodity.

It’s encouraging to see that many start-up companies in the recycling sector are finding success by addressing exactly these problems in innovative ways. Spanish firm Sulayr[10], for example, has developed a new technique for delaminating layered complex plastic packaging, returning the different plastics to the supply chain.

Successful as they have been in solving the difficulties around compound materials, even they do not share the point of view that merely reducing unavoidable waste and increasing recycling is enough to make the packaging industry sustainable, though.

Sulayr is working with several partners in the plastics manufacturing industry including BASF and Bobst[11], to develop layered plastics that would be easier to separate, reducing the amount of energy required to complete the recovery.

When packaging is designed and manufactured without thought being given to the end-of-life stage, total recycling is almost impossible to achieve due to the complications of recovery and, in many places, the lack of facilities to recycle complex products.

If we also consider the carbon emissions of the packaging industry, recycling is better than disposable packaging, but still incurs a high cost over reuse models. The recycling industry is the largest greenhouse gas emitter of the waste disposal sector[12] emitting 13 billion tons of CO2 in the UK alone per year, largely due to the high temperatures required.

Reuse over recycling

Research carried out by the University of Utrecht[13] indicates that a reusable plastic bottle is responsible for less than half of the amount of carbon emissions over its lifetime than a single use equivalent, even if both of them are recycled at the end of their useful lives. And if possible, composting releases fewer greenhouse gases, but the range of compostable hard plastics is still small.

Waste with high rates of recycling such as cardboard can greatly help with the waste problem, but I believe the ultimate goal must be true sustainability, rather than meeting limited targets for reduced but still problematic harm to the environment.

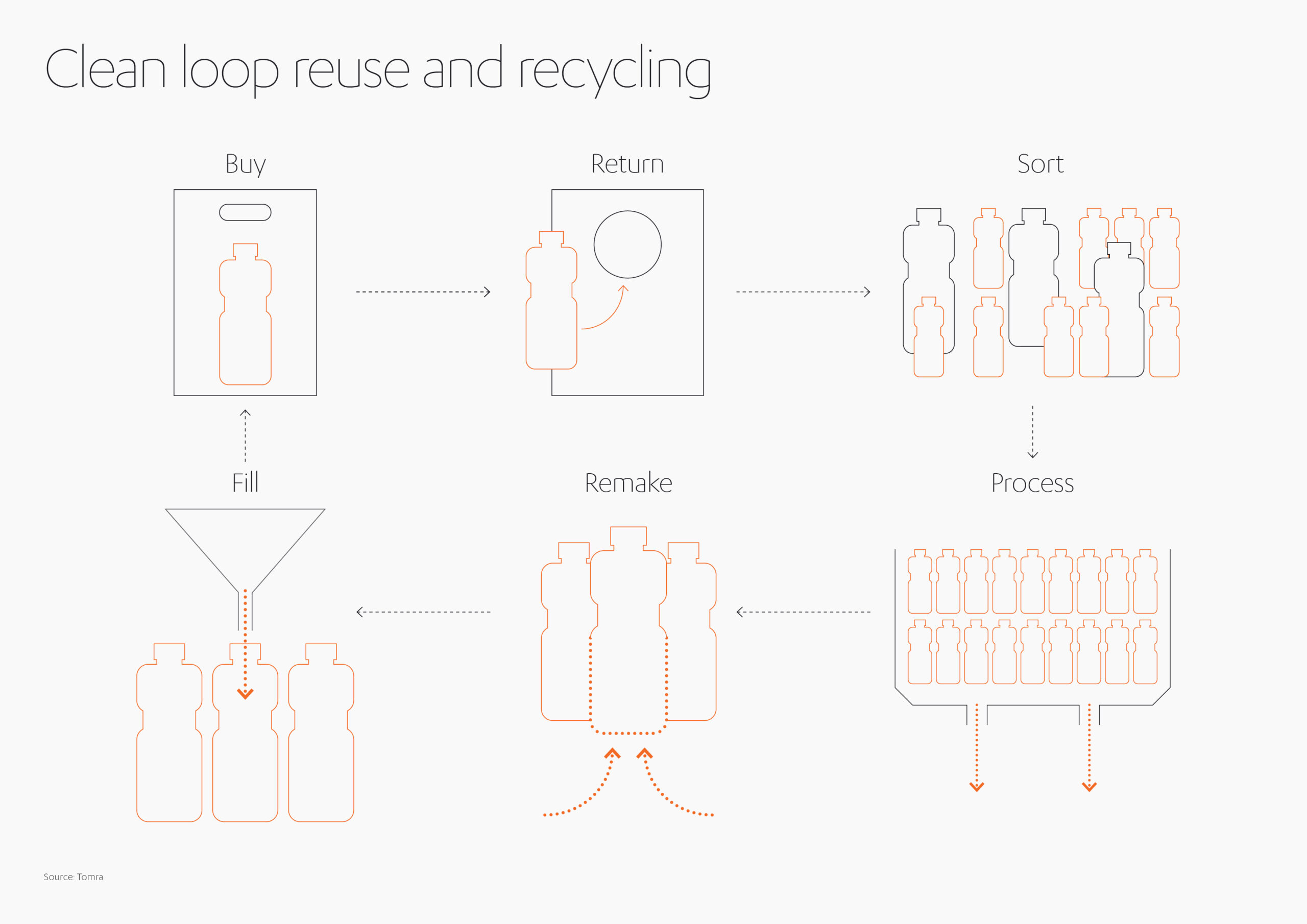

For packaging to be truly sustainable, the industry must break the chain of raw materials being created, used and disposed of altogether. Rather than a line from manufacturer to disposal, packaging must become a cycle – and a low-carbon cycle at that.

Why do we need packaging at all? Wouldn’t it be better to do away with it if it causes so many problems in its disposal and management?

Many of the products we rely on depend on packaging to be useable at all. The recent roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines would have been impossible without a cold distribution chain[14] and individual sterile containers, for example, both originally developed for the distribution of chilled fresh and frozen food to supermarkets.

Food waste, too, would be enormously increased if fresh food was to be sold unpackaged, as the carefully designed packaging exists to protect the products and extend shelf life. No one profits from spoiled food, so business imperatives and the desire to reduce waste work hand in hand.

Now, innovators in the packaging and recycling sector are looking to go further and entirely eliminate packages waste, without losing the many advantages it delivers.

Rethinking the purpose of packaging

Loop, a division of US recycling company TerraCycle, is one of those companies leading the way with experiments in reusable packaging.

Reuse is, of course, not a new idea. Many British people will remember when milk was delivered to the door in glass bottles, which could then be returned, sterilized and reused by the dairy. Propane gas has always been sold in returnable cylinders and breweries distribute their beer in barrels to be sent back when the next order is delivered.

European supermarket shoppers have become used to bringing their own bags rather than buying new bags each time, and coffee shops around the world are rewarding customers for providing their own reusable cups, but other industries have found the process more difficult to establish. Takeaway food in most countries is almost always provided in a disposable container, for example, and despite the best efforts of a number of independent shops such as Original Unverpackt[15] in Berlin and the Good Bottle Refill Shop in New Jersey, buying food, cleaning products and toiletries from large hoppers to refill customers’ own containers has never really caught on.

Loop attempts to offer consumers the convenience of prepackaged goods along with the associated benefits to the supply chain, but without the waste problems of disposable packaging[16]. Items are bought in shops in Loop containers or delivered to consumers’ homes along with a specially designed container, into which go empty tins, cartons and bottles when their contents are used up.

Loop then collects the container, dropping off another, and instead of recycling the packaging or sending unrecyclable packages to landfill, they are washed and reused. Once they become damaged or otherwise unusable, they are completely recyclable or compostable using TerraCycle’s processing plants.

In this way, Loop eliminates packaging waste altogether. In the US, the company has its own e-commerce delivery service and, in the UK, it has partnerships with major names including Tesco, the country’s largest supermarket chain, Procter & Gamble and Burger King.

Tom Skazy, CEO of Loop, has suggested that homes will soon have a standardized ‘reuse’ bins alongside their recycling bins, in which they will put reusable containers as naturally as they currently sort glass and paper.

Research by McKinsey, the management consultancy, has indicated that customers in some segments are willing to pay up to 5% more for recycled packaging, but are unsure of what needs to happen to achieve sustainability[17].

Circular economy initiatives such as Loop’s provide an easily explained and complete solution. While McKinsey calculates that recycled packaging only adds 1% or 2% to the retail price, experiments are still being conducted to find the price of reuse and the operating models are still being refined.

Loop is far from being the only company to apply circular economy principles to packaging. Another example is LimeLoop[18], which makes shipping packages that can be used hundreds of times then completely recycled. Or there is Olive[19], a fashion packaging company that uses reusable packaging in conjunction with logistical planning to eliminate waste in clothing delivery, while DeliverZero[20] is addressing the problem of disposable takeaway cartons.

Circularity leads to sustainability

The ‘reduce and recycle’ approach to packaging has undoubtedly been a hugely positive step forward from previous policies of incineration or landfill disposal. But I firmly believe that for packaging to become truly sustainable, and for us to have any hope of achieving our climate change objectives, a packaging revolution is required, with nothing less than total sustainability as its objective.

Circular packaging supply, designed around reuse, design for disposal and cradle-to-grave materials management that eliminates waste and minimizes the amount of energy required for recycling, needs to become the norm, rather than the exception.

Carbon net zero is already widely accepted as a business aim. It is time for us to put packaging waste zero onto corporate agendas, too.

[1] https://www.metsagroup.com/metsaboard/investors/operating-environment/global-packaging-market/

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0956053X16303300

[3] https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Packaging_waste_statistics

[5] https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/containers-and-packaging-product-specific

[6] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31994L0062

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/11/world/china-recyclables-ban.html

[8] https://www.ft.com/content/360e2524-d71a-11e8-a854-33d6f82e62f8

[9] https://www.afandpa.org/news/2022/unpacking-continuously-high-paper-recycling-rates

[11] https://spnews.com/closed-loop-multilayer/

[12] https://www.esauk.org/application/files/5316/4268/8976/ESA_GHG_Quantification_Final_Report_23_06_2020_Issued.pdf

[13] https://zerowasteeurope.eu/library/reusable-vs-single-use-packaging-a-review-of-environmental-impact/

[14] https://www.pfizer.com/science/coronavirus/vaccine/manufacturing-and-distribution

[15] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652619323960

[16] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/loop-s-launch-brings-reusable-packaging-to-the-world-s-biggest-brands/

[17] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/creating-good-packaging-for-packaged-goods

[18] https://www.forbes.com/sites/sap/2022/02/11/sustainable-packaging-for-retailers-offers-guilt-free-shopping-experience/?sh=4c83109726fb

[19] https://techcrunch.com/2022/09/14/reusable-packaging-olive-b2b-clothes-landfills/

[20] https://www.deliverzero.com/

Cartoon image illustrated by Graeme MacKay

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit