Electric Vehicles… more than just cars

If asked to visualize a near-future world dominated by electric vehicles (EVs), certain images might immediately spring to mind: Fleets of SUVs cruising serenely down the highway; ride-hailing taxis rolling to a stop at your doorstep; self-driving saloons allowing you to unwind with film or book mid-journey.

However, to limit our concept of electric mobility only to cars is to ignore exciting developments unfolding elsewhere in the EV market, where a range of other battery-powered vehicles are generating quite a buzz of their own.

Electric micromobility vehicles (EMVs), those designed to convey one or two passengers in economic and eco-efficient style to their destinations, are rapidly becoming a top choice among consumers. Market growth suggests these alternative transport choices – devices like e-mopeds, three-wheelers, e-kickscooters and e-bikes – will be key ingredients in the private transport formula over the coming decades as the on-demand mobility ecosystem continues to develop . . . and become more integrated.

Forecasts show the global micromobility market is tipped to reach US$ 214.57 billion by 2030, up from US$ 44.12 billion in 2020.[1] Consumers don’t need much of a push to make the switch to EMVs. During the Covid-19 pandemic, for instance, global e-bike sales spiked by 240%.[2]

One recent survey for global business consultants McKinsey & Company suggests some 70% of workers worldwide would consider using a micromobility device for their daily commutes. This, in McKinsey’s analysis, indicates that “a growing number of workers may gravitate toward smaller, more environmentally friendly forms of transport”.[3]

The numbers make a convincing case. Globally, 40% of people say that bicycle (including electric variants) would be their preferred micromobility commuting option, followed by e-mopeds (16%) and e-kickscooters (12%). Fewer than one-third of those surveyed (31%) did not include micromobility among their top commuting choices.

The future, it seems, is small, green and convenient.

Regional trends demonstrate market diversity

While the global trend is unmistakable, the same survey also exposes regional differences in readiness for EMV adoption. China proved most pro-EMV, with 86% of respondents favoring a micromobility commute; declining to 81% in Italy; 67% in France; 65% in Germany; 60% in the USA; and 55% in the UK.[4]

Long-term transport trends help explain these differences.

The USA, with its long and storied relationship with the automobile, has an entrenched four-wheeled heritage to appease. Countries with cooler and wetter climates, such as the UK, are likewise more reluctant to surrender the protection of a traditional car and risk exposure to the elements.

With their moped-focused cultures, conversely, citizens of countries such as China and Italy have been pursuing micromobility solutions long before the term was even popularized. China is now the market leader in e-mopeds, with sales rising from 20 million in 2015 to 30 million in 2021.[5] Significantly, two-thirds of all motorized two-wheelers sold in China are now battery-powered.

In India, traditional home of the tuk-tuk, motorbikes and autorickshaws have long been blamed for the country’s worsening pollution levels – to the extent that the government is banning all non-electric two and three-wheelers from 2025.[6]

Micromobility is ready to plug the gap. More than 11,000 new electric rickshaws are now produced in India weekly, adding to the 1.5 million already on the roads.[7] With daily recharge costs six times cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives, their growth makes economic sense.

India’s micromobility market was valued at US$ 273.7 million in 2021 and is forecast to swell to over US$ 2 billion between now and 2032.[8]

Greaves Electric Mobility, the Indian EV pioneer in which Abdul Latif Jameel is a key investor, is one of those businesses leading the charge. The company unveiled its latest range of electric two- and three-wheeler vehicles at India’s Auto Expo 2023 in January, along with ambitious plans for growth.

Greaves is already one of the country’s leading two-to-three-wheeler EV mobility companies, with a range of cleaner and more efficient vehicles that are accessible to communities in India. It is one of the fast-growing EV brands in the country, with retail sales of 70,390 for full year 2022, a 398% increase over the same period last year. Its two-wheelers, sold under the brand name Ampere, commanded a market share of 13% in 2022.

Laws can make or break EMV uptake

A deeper dive into the regulatory environment governing EMVs around the world shows how legislators can become champions of sustainable personal transportation – and help hasten the overdue switch to battery-based vehicles.

Practicality is the cornerstone of EMV adoption. If the right legislation is passed, the right infrastructure put in place and the right price point achieved, buyers will vote with their pockets. In China, for example, motorists do not need to have a license for vehicles unable to exceed 25 Kph, leading to a disproportionate demand for traditional (and therefore also electric) mopeds.

Rentable e-kickscooters find particular hubs of willing adopters in France (18%), Germany (13%) and the USA (13%), where sharing schemes are already well established.

In contrast, e-kickscooter take-up has been sluggish in China (6%) and the UK (10%) where lawmakers have limited their use over safety concerns. In China, the two largest cities, Beijing and Shanghai, banned e-kickscooters from the roads in 2016, after a spate of accidents.[9] Similarly, private e-kickscooters have until now been outlawed from all public roads and pavements in the UK, under threat of driving bans, fines and vehicle confiscation.[10] However, watch this space: Trials of shared e-kickscooters are currently under way in 30 locations around the country, and could yet transform the devices’ fortunes in the UK.

Should we be surprised by micromobility’s worldwide upswing? Perhaps not, in a post-Covid world where people remain wary about sharing enclosed spaces with groups of strangers. Figures show bus and train use in the UK remains 20% to 30% lower than before the pandemic.[11] Increasingly, people are seeking smaller, more private solutions to their transport needs – hence the rise of eco-friendly EMVs.

Yet it would all count for little without the right equipment and support structure in place, to both encourage EMV adoption and to promote its viability as a long-term solution to our urban transport needs

Robust infrastructure transforms appetite for EMVs

Post-pandemic, with a new focus on hyperlocal mobility, regulators around the world are beginning to lay the foundations for EMVs’ ascension.

In the USA, an ever-expanding network of ‘greenways’ is one small yet significant step towards weaning the nation off its automobile addiction. These traffic-free routes (open to users of e-bikes) are growing at an unprecedented rate and could eventually form a vast interstate system. Standout schemes include the ongoing 3,000 km East Coast Greenway linking Maine and Florida, Atlanta’s BeltLine, Chicago’s The 606, and Detroit’s Joe Louis Greenway.[12]

Even New York City, so long synonymous with the honking of car horns, has earmarked US$ 723 million for completing a greenway around Manhattan later this decade. Initiatives such as this are encouraging businesses to innovate, too. E-bike provider Joco, for example, is using private premises such as offices and hotels throughout Manhattan for battery charging, keeping the sidewalks clear of idle vehicles.

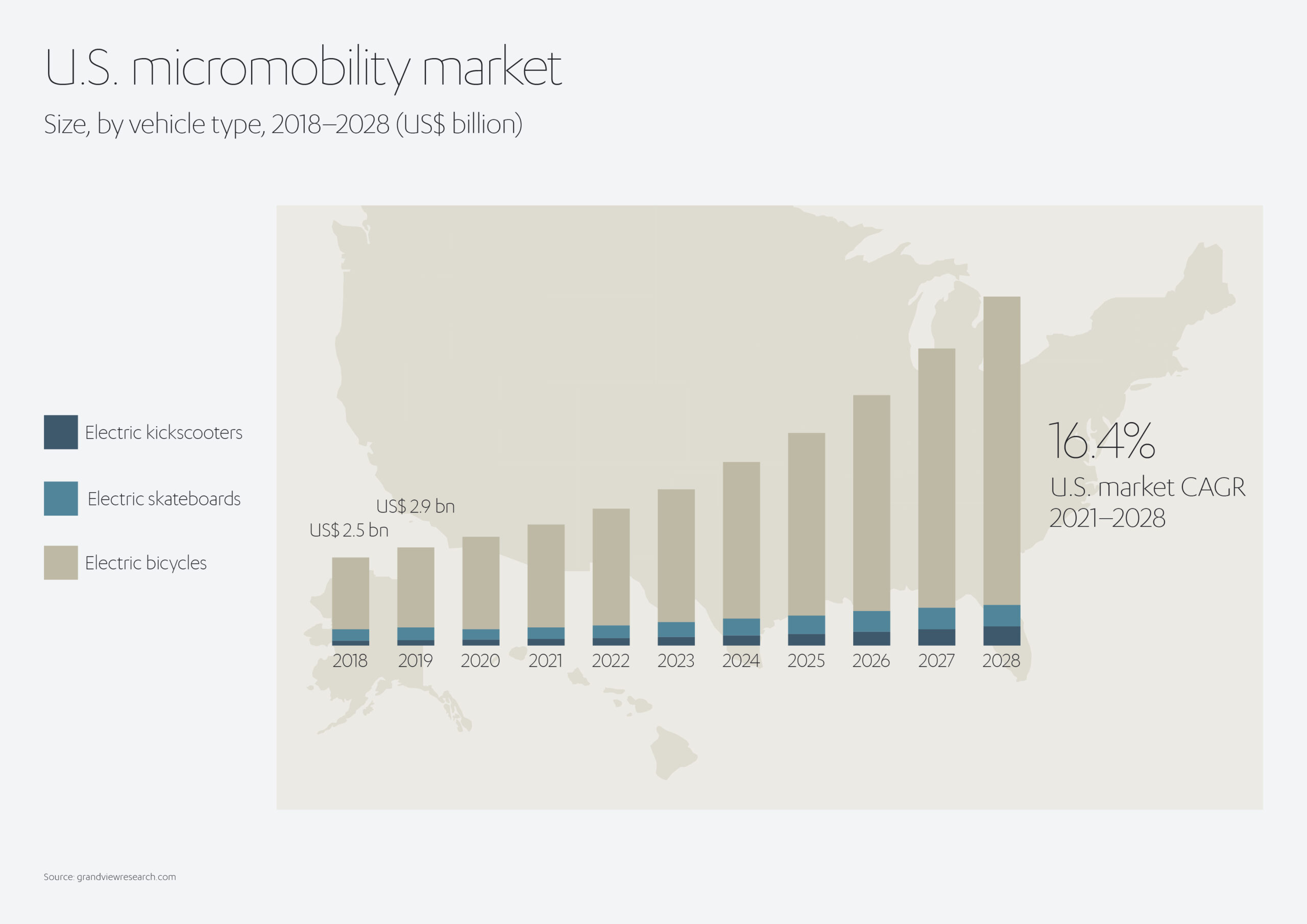

Little shock, therefore, that from a low starting base Americans are gradually embracing EMVs. Two-thirds of all EMV trips over the past decade in the USA happened in just the last two years – a trajectory that so far shows no sign of slowing.

Beyond the USA, EMV innovation is a truly global endeavor, with fast developing infrastructure and technology boosting the cause of battery-powered micromobility.

A pilot scheme in Paris, France, has seen Estonian startup DUCKT unveil 150 docking stations designed to draw power from existing infrastructure such as streetlights, advertising hoardings and bus stops.

Authorities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, meanwhile, are establishing a municipal fund for infrastructure improvements (small vehicle lanes, scooter parking) via revenues from vehicle permits.

Innovation can also mean inclusivity. In Zapopan, Mexico, EMV providers and operators are encouraged to accept multiple payment methods from potential customers – making eco-travel an option even for residents without bank accounts or cell phones.[13]

Many countries, such as India, are experimenting by cutting taxes and offering subsidies on EMVs to stimulate demand. In the USA, as part of Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill, rebates of up to US$ 900 are available for buyers of e-bikes.

We are also witnessing the emergence of more bespoke EMVs, purpose-built for fulfilling a specific need. See AYRO in the USA, for example, whose low-speed vehicles are widely deployed for transporting vaccines; Greaves Electric Mobility’s electric cargo three-wheeler, which wowed audiences at AutoExpo 2023; or Swobbee and ONO in Germany, providing emission-free deliveries via electric ‘cargo bike’ on behalf of package courier Hermes.

Germany serves as a telling example of EMV economics, leading the continent’s e-kickscooter transition with a potent mix of legislation and entrepreneurship.

German city planners are increasingly converting car lanes into cycle lanes, improving the safety prospects of the 65% of Germans who would consider using bicycles, e-kickscooters, and mopeds for their daily commutes.[14] Providers of micromobility-for-hire machines have also been experimenting with innovative pricing structures, balancing the merits of one-time unlocking charges against per-mile fees. In a convenience-driven market like micromobility, where customer loyalty is threatened by breakdowns or empty vehicle racks, German providers are mastering logistics. They have invested heavily in data, ensuring the right number of cycles/scooters/mopeds are in the right spots at the right times. And they have secured prime downtown locations for service and storage facilities, sharply improving reliability.

As a joined-up strategy, it packs a punch. As of 2021 the largest fleet operators in Germany managed a portfolio of some 120,000 e-kickscooters. That year, around 90% of Germans took at least one trip on an e-kickscooter, translating to around US$ 110 million in revenue.[15]

Infrastructure is key

We have seen how the EMV transition relies not only on legislative support and private sector innovation, but also on next-generation infrastructure.

The common thread uniting all EMV devices is the need for periodic recharging. That is why tracking the number of electric charge points can help us take the pulse of the industry. And so far, its vital signs are healthy.

In the UK, for instance, 2022 saw the number of public charging points in the UK exceed 30,000 for the first time, up 33% in a year. Promisingly, the number of rapid-charge devices – those capable of recharging a piece of kit within the constraints of busy working lifestyles – ballooned to almost 5,500. The UK government’s £1.6 billion Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Strategy is targeting 300,000 public charge points installed by 2030.[16]

Europe as a whole crossed the 300,000 slow charger threshold in 2021, up 30% from the previous year. In the same period, the number of public fast chargers in Europe rose by almost one-third, approaching 50,000 units. [17]

Globally, almost 500,000 new charge points were installed in 2021 – more than the total number of charge points available just four years earlier. EMV innovation hub China leads the way, inevitably, increasing its publicly-available chargers to around 680,000 in 2021 – a 35% year-on-year increase.

Technology holds the key to EMVs consolidating their market foothold and becoming a mainstay of the private transport mix.

How tech is turbocharging micromobility market

Fears over battery cost, lifespan, range and recharge times have long been blamed for hindering the adoption of all electric vehicles, including micromobility devices. However, rapidly-evolving battery technology is gradually allaying these concerns.

The cost of lithium-ion batteries is predicted to fall by 6.5% annually over the next decade, dragging down the price of EMVs proportionally.[18]

In addition, a new breed of batteries based on military and industrial tech promises safer, faster and more sustainable battery charging in urban environments.

These lithium-titanate (LTO) batteries have generally been used in much smaller or larger devices, like cell phones or automobiles, and suffer from unique voltage profiles leaving them unsuited to EMVs. Recent hardware and software breakthroughs have helped overcome problems associated with LTOs, using sensors to automatically regulate voltage and dramatically improve integration.[19]

LTOs now surpass the performance of traditional lithium-ion batteries across a range of micromobility metrics. The hyper-sensitive electrode surface area of LTOs means batteries can be fully charged in less than 20 minutes, and endure many more charging cycles before expiring.

Free of nickel, manganese, aluminum, and cobalt oxides, LTO batteries also reduce the fire risk associated with early rechargeable batteries. Honda’s EV-neo moped is already using the technology, while California-based startup ZapBatt is developing similar chemistry for use in electric bikes and scooters.

Since EMVs are lighter than automobiles and do not need to boast such expansive ranges, some companies are experimenting with sodium-ion batteries for e-bikes and scooters.[20] Not only are these cheaper, reducing unit costs, but they also rely on more easily-acquired materials than the rare-earth elements of lithium-based alternatives.

Still, as batteries gravitate from ‘problem’ to ‘solution’, other roadblocks persist in the way of an EMV-driven future.

Hurdles remain on highway to EMV takeover

Image matters. If micromobility fleets are rolled out too hastily, lacking appropriate support services, broken-down vehicles can end up littering the streets, risking long-term reputational harm.

Shared e-bikes and e-kickscooters continue to suffer from vandalism and theft, reportedly affecting up to half of some fleets. Companies like Mobike and GoBee have halted trials in Europe due to the issue.[21]

As the market matures and consolidates, there are wider concerns about fresh venture capital (VC) money disappearing from the sector. Newer entrants, it is feared, might struggle to become established in the face of onerous licensing and insurance obligations.

Many micromobility schemes depend on online booking and journey planning. Unreliable, low-speed internet connectivity in many parts of the developing world continues to prevent EMV technology from fulfilling its potential in these markets.

The industry is also weathering a global shortage of integral semiconductor chips, the bottleneck triggered by a perfect storm of COVID-19, the US-China trade war and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Against these challenging conditions, companies must still find a way to ratchet down costs. A recent survey found more than one-third of potential micromobility customers were deterred by prices.[22]

These problems, and others, help illuminate why the micromobility transition is more of an evolution than a revolution. Even in Europe, micromobility devices are presently used for less than 0.1% of travel within cities.[23]

But this is no reason to abandon the venture – not when the rewards are potentially so great.

One recent study expanded micromobility data from Munich, Germany, across more than a hundred European cities to explore the possible social benefits of EMVs.[24] The report found that by 2030 the launch and maintenance of EMVs could:

- create one million new jobs in Europe

- offset 30 million tons of CO2 emissions annually and save 127 TWh of energy use

- increase European GDP by €111 billion with fewer worker hours squandered due to traffic congestion

- free up more than 48,000 hectares of valuable inner-city land

Are we collectively doing all we can to ensure these dreams of a clean, green EMV-driven future come to pass?

Leading the drive towards cleaner roads

Ensuring EMVs occupy a lasting place in our urban environments will mean bold investment and strategic thinking.

City planners need to design fully interconnected transport networks to seamlessly link people with the jobs and businesses they frequent. Harmonization is key; a disjointed system that leaves people stranded will win few converts.

A successful EMV ecosystem demands digital as well as mechanical expertise. Well-designed phone apps, driven by live data and managed by AI, can help with coordination and communication. Apps permit users to monitor the movements of trains, buses and e-scooters/bikes, ensuring there is always an EMV waiting for them when disembarking.

To promote inclusivity, city licensors should ensure that EMV services extend to disadvantaged areas by making it a requirement of the tender process. Micromobility operators must work closely with city planners to design shared pricing structures, and to guarantee the funding of necessary infrastructure.

City authorities must move away from a car-first mandate and shift focus to micromobility, designating more roads as solely for EMVs. Micromobility operators need to think tactically too, tailoring their offering for different locations worldwide based on geographic and cultural needs. Expanding a fleet of e-bikes to include mopeds might involve a high initial outlay, but could help secure new long-term custom if market demand exists.

Innovative thinking can help micromobility schemes integrate with – or even improve – existing public transport systems. Live cameras mounted on mopeds and e-bikes, for instance, could help equip cities with vital information about traffic levels and road maintenance issues – or could even be monetized by providing Street View footage for Google.

Deputy President and Vice Chairman

Abdul Latif Jameel

Here at Abdul Latif Jameel, through our partnership with Greaves Electric Mobility, not to mention the Jameel Family’s existing investment with US EV pioneer RIVIAN, and JIMCO’s investment in Joby Aviation, we are demonstrating how the wider private sector can help ease the mobility transition.

“Mobility is a major contributor to global carbon emissions. At Abdul Latif Jameel, we are embarking on a long-term journey to support partners who can contribute to delivering cleaner, more sustainable and, crucially, affordable transport options to communities around the world,” said Hassan Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman, Abdul Latif Jameel.

It might be electric cars dominating the imagination and grabbing the headlines – but thanks to their competitive prices and inherent versatility, it is perhaps EMVs that will unlock the environmental and inclusivity potential of battery-powered personal transport.

[1] https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/micro-mobility-market-A11372

[2] https://techcrunch.com/2021/12/27/micromobility-in-2022-refined-mature-and-packed-full-of-tech/

[3] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/why-micromobility-is-here-to-stay

[4] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/why-micromobility-is-here-to-stay

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-11/hackers-are-helping-to-speed-up-china-s-electric-scooter-boom

[6] https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/25/energy/altigreen-india-electric-rickshaw-spc-intl/index.html

[7] https://www.cleanfuture.co.in/2019/01/04/tuk-tuk-the-silent-ev-revolution-of-india/

[8] https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/micromobility-platform-market

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-37227562

[10] https://electricrideoncars.co.uk/electric-scooters-for-adults-kids-are-they-legal-in-the-uk/

[11] https://www.ice.org.uk/news-insight/news-and-blogs/ice-blogs/the-infrastructure-blog/what-is-the-future-of-public-transport-after-covid-19/

[12] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferdungs/2021/07/19/why-micromobility-deserves-a-front-seat-in-the-infrastructure-discussions/

[13] https://thecityfix.com/blog/3-ways-cities-can-leverage-micromobility-services-for-good/

[14] https://www.mckinsey.com/features/mckinsey-center-for-future-mobility/mckinsey-on-urban-mobility/what-germany-can-teach-the-world-about-shared-micromobility

[15] https://www.mckinsey.com/features/mckinsey-center-for-future-mobility/mckinsey-on-urban-mobility/what-germany-can-teach-the-world-about-shared-micromobility

[16] https://www.moveelectric.com/e-cars/number-uk-electric-car-charging-points-jumps-33

[17] https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2022/trends-in-charging-infrastructure

[18] https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/micro-mobility-market-report

[19] https://www.automotiveworld.com/articles/lithium-titanate-could-prove-the-new-driver-of-micromobility/

[20] https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/01/04/1066141/whats-next-for-batteries/

[21] https://guidehouseinsights.com/news-and-views/can-shared-micromobility-prevail-against-anti-social-behavior

[22] https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/the-future-of-urban-mobility

[23] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferdungs/2021/07/19/why-micromobility-deserves-a-front-seat-in-the-infrastructure-discussions/?sh=6cc3c4d02f59

[24] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferdungs/2021/07/19/why-micromobility-deserves-a-front-seat-in-the-infrastructure-discussions/

1x

1x

Added to press kit

Added to press kit